A Patron Saint for Broken Homes: Shahrukh Alam

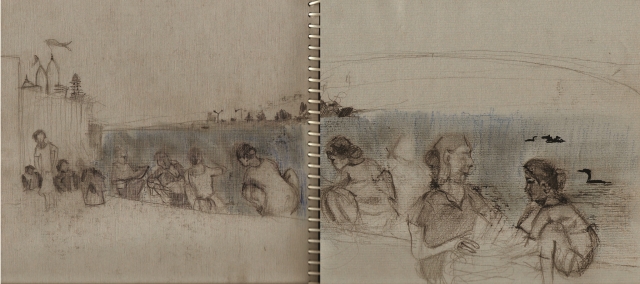

Art: Samia Singh

“Kar-e-jahan daraz hai…” (Long and complicated are the affairs of the world.) – Iqbal.

Munni apa felt pleased today.

She generally regarded herself as the only sane person in her family. And she let everyone know this. “Hmmph, this family! They cannot control their temper. I have suffered all my life for this. My father-in-law owned land in our village near Basti. ‘He’ fought with his father and dragged all of us away to this hell. From being a farmer’s son, he came to be a factory-worker. I was reduced to living in this shanty. Our eldest son: could never keep a job. Instead, he loses his temper and sends his wife away, one morning. For what? She had gone to the annual Urs at the Bade Pir Sahib ki dargah and had stayed there the night. Now, I have to do everything. (Not that she was much help, anyway.) The second son is an auto-driver. Earned a decent amount every day and brought home his earnings, mind you. He looked after me well, until that wretched girl entrapped him. She forced him to elope. Obviously, he had a proper nikah first and only then brought her home, but his father forbade him from entering. Only earning member thrown out of the house.”

At this point in her story, Munni apa would always lean closer and whisper: “The girl is Hindu. That is the main problem. She is a divorcee with two children. That is also the main problem. But, of course, if he could just control his temper, my son would still be living at home. Bad temper – that is the main problem.”

Then Munni apa would bemoan her youngest child’s temper. “My daughter has taken after her father and her brothers. She will be the cause of my death. She has fought with her husband and come here. What am I to do now? I don’t even have a responsible man in the house who will take her back, apologize to her in-laws, and settle her in.” And some of the women of Dani Limda would say, “Munni apa, you do everything yourself. Why don’t you go to your daughter’s house and apologize? Or, better still, invite the father-in-law here; request him to come and fetch her. We will lay out a feast for him.” Others would suggest that she pray at the dargah of Bade Pir Sahib. “The husband will himself come and plead with her to go back.”

Bhairvi Devi would slowly nod in agreement. She was the matriarch of Dani Limda.

She had arrived in the city, together with her now deceased husband, almost fifty years ago from a small village in Rajasthan. The newly wed couple had come to look for work and had found it in the textile mills. They had made their home by an old, crooked lemon tree in an abandoned stretch of land close to the factory grounds and had called it Dani Limda. Slowly, over a period of time, other families came to live there too but Bhairvi Devi did not let anyone forget that she and her dear, departed husband were the ‘founding fathers’, so to say.

She felt that she particularly needed to remind Munni, who seemed to be readying herself to take on the matriarch’s mantle. “I remember the day you first came to Dani Limda,” Bhairvi Devi would often say to her, “from some small village near Basti. You were so shy. So young…”

Of late though, Bhairvi Devi had focused solely on the advice that she must render: “Yes, go to the dargah. Tie a length of red string in the jaali. Ask that your children’s troubles get over soon. That your daughter returns, that your eldest son’s wife comes back home and that that scoundrel’s divorcee wife leaves him and goes back to her house.”

For the last one month, Munni apa had followed all the advice. She had prayed at the dargah and she had made three trips to her daughter’s house trying to placate her in-laws. “Arre sahib, at least come and have a meal at our house. Don’t speak to her; don’t even look at her face. Come for my sake.” And today, after weeks of persuasion, the father-in-law had finally relented. He had sent his younger son with word that he would come on Sunday. Munni apa felt pleased today.

Anwar, on the other hand, felt extremely annoyed. At the best of times, he found it difficult to remain calm against his mother’s incessant ranting; today was a different matter altogether. He had heard the most disturbing piece of news at the tea-stall.

“You behave yourself when he comes to our house. Or your sister will never go back home. Bring some gosht – good fleshy pieces, not bony ones. Bring some dahi also. And jalebi – I’ll serve some and pack the rest for him to take back. Bring chana, milk for the tea…”

“We may not have a home when he comes,” Anwar snapped.

Munni apa looked up, vacantly: “If your father creates trouble – or your sister – I am telling you… I have had enough of this family’s tantrums. If you all don’t co-operate on Sunday, I’ll leave this house and go live in the dargah. Then we’ll see who runs the house. Nobody will have a home.”

“Arre Amma, listen to what I have to say? They are saying at Babu’s tea-stall that our colony is going to be demolished by the Municipality under the new scheme. We don’t have land papers, so we will have to go.”

“Go where?” Munni apa blinked stupidly.

“I don’t know. Abba and you decide. I’ll come wherever you go. They were saying that the Municipality would demolish Ramdhun Bazaar, Madhavpur, Pheriwaalon ki chaali and Dani Limda this week, so we will have to find a fifth place to live.”

As she listened to her son, Munni apa stood still and speechless. But only for a moment. Then she said quite reasonably, “They won’t demolish anything. It has been thirty-three years.”

“Amma, these demolition drives are very unpredictable,” the daughter spoke for the first time. She was still uncertain whether she wanted to feel sullen or coy about her father-in-law’s visit. Though she most certainly did not wish it to fall through without event.

When they assembled that evening on the steps of the small, raised platform that served as Dani Limda’s temple premises, dedicated (upon Bhairvi Devi’s insistence) to Karni Mata, Munni apa had several important concerns that required immediate attention from the women.

“This Anwar is not very reliable but it is best to be prepared, I say.”

“He is creating trouble because he does not want the father-in-law to visit. The girl did not just leave her husband’s home like that; she got encouragement from her brother,” pronounced Bhairvi Devi wisely. She continued, “If they had to demolish the colony, would they have waited fifty years? Would they have allowed all of us to build our homes here? For our children to grow up, marry? What rubbish, this demolition drive.”

“But if there is any trouble, if the officers come, then do explain all this to them. Tell them you built your house here fifty years ago. Tell them your husband died here. I wish we had a grave to show for it, but anyway… Just don’t let anything happen on Sunday.”

“You tell them. You have become the colony’s new leader. My days are now over. I have grown old; I have been retired. You speak to everybody. You speak on behalf of everybody. You talk to the officers.”

Munni apa spread out her palms, looked around and smiled. “But you came here years before I did. You saw everything. You remember when this place was an abandoned lot; when I was young and shy…” Everyone smiled with her. Even Bhairvi Devi, though abashedly.

“And tell your daughter to wear something appropriate – a sari. She has begun traipsing around without any purdah, these days,” she said.

“I don’t know if we should parade her in front of him. I promised him that he wouldn’t even have to meet her. He is coming only to have lunch.”

“Uff! Don’t be silly! Isn’t it understood that after he eats lunch, he is expected to make some conciliatory gestures, set a date to take her back?”

“Of course, he will do that. But we don’t have to make it that obvious. She will go back to her own house insha’allah. Won’t she, Bhabhi?”

“Sing a tona,” Bhabhi said. In her village, when women wed their daughters, they sang songs that invoked magic in order to charm the groom into submission.

She began to sing and Munni apa joined in:

“Devrhi na chhodega damadva, re mai

Mor bhala tona

Arre, tukur-tukur dekhega damadva, re mai

Mor bhala tona”

Anwar sighed at her unperturbed ignorance. He had spent the evening at Babu’s tea-stall – well beyond the temple steps, which seemed to be the place where all his mother’s ideas and impressions got formed. Rather limiting he considered it to be. Not quite the same as spending time at the tea-stall, or knowing important people like the sajjadah nashin at the dargah, or the councillor’s nephew, or those very knowledgeable boys at Ramdhun, who seemed to know people in the police department. He only wished his mother would notice.

On the streets, there was definite news that they were coming. Anwar was naturally worried. He was worried too for the rather generous variety of food that his mother had ordered him to buy for that man’s visit. Unless his sister was really serious about going back with her father-in-law, the dahi, the gosht and the jalebis would all be wasted on him. That should first be settled, he felt.

“Don’t glare at me. What have I done?”

“Amma wants so many things for his lunch – gosht and dahi and jalebis and milk. And we can’t even be sure if we’ll have our house by then.”

“If our house is demolished before Sunday, we’ll send word that lunch is cancelled and eat everything ourselves,” she giggled.

“And if the house survives till Sunday and he eats all of it, wouldn’t that be a waste?”

“But he’s been invited to lunch!”

“But are you going back to your husband?”

“Of course, she is going back. Aren’t you going back, lal? Of course, she will go back home, she will go back to her family…” Munni apa said cajolingly. “Anwar, beta, don’t always imagine the worst. That is the problem with you, always brooding, always annoyed.” His sister nodded gravely, her eyes sparkling with laughter.

The Municipal Corporation’s ‘Dabaan Department’ comprised two slightly built supervisors – Sharma ji and Gupta ji – a rickety bulldozer and its driver and half a dozen daily wage labourers who were the ‘demolition men’.

At 10:45am on Friday morning, Sharma ji was waiting impatiently for his counterpart to arrive in office when the door opened. “What is this, Gupta ji? You are late again. We’ll never get through Pheriwaalon ki chaali if we start at noon. You should have some sense of duty.”

“Do you know where I have to commute from every morning, Sharma ji? I come from Sikandarabad change three buses. I have not been allotted a type II flat in the centre of town like some. Anyway, has the police escort arrived?”

“Sir, police reinforcements have to be booked 72 hours in advance. How can I make bookings when there is no surety of time? We were supposed to start at 9am today, but you are arriving in office at 10:50.”

It was true that Sharma ji worked under difficult and ever changing conditions. At times, the supervising officer forgot to tell him, until the last possible minute, which particular colony he was supposed to be cutting on a particular day. How could he ever book an escort party, where details had to be filled 72 hours in advance?

“Sharma ji, have you lost your mind? I have small children. I am not going into any chaali without police protection. Don’t you remember the pathrao last month? We barely escaped the stone pelters. Now, how can you even suggest something so foolhardy? And these pheriwaalas- they will throw their wares at us when they run out of everything else. You will be hit on the head with a cabbage…”

A primary difference between Sharma ji’s and Gupta ji’s styles of functioning was that the latter invariably exercised free will in situations that the former felt required complete submission. For instance, demolition schedules, office timings and suchlike.

“Gupta ji, but duty is duty. We have a list of places that have to go before Monday.”

Gupta ji did not think much of dutiful types. It was his belief that the role suited wives much better. But harmony had to be restored. He asked for the list, fished out his reading glasses and carefully read out the names of colonies marked for demolition.

“Impossible to do by Monday. One bulldozer they have given us. Plus Sharma ji, don’t even count Sunday. Impossible to work on Sundays. Everyone is at home in the colonies; they start pathrao at the drop of a hat. Most destructive, on a Sunday. Free picnic for everyone.”

But Sharma ji persevered, so Gupta ji plodded through the list.

“It’s already almost noon. No point going to Pheriwaalon. We won’t finish in time. Let’s do this Dani Limda place. It is small – 20 or so huts.”

“But that is not due until next week.”

“Then let’s sit in the office. That is even better. I am not going to Pheriwaalon without protection. You can tell sahib.”

Between spending the day sitting idle at his desk and demolishing a colony not due to be done in until next week, Sharma ji chose the second option. He reckoned it was as close to performing his duty as circumstances – and Gupta ji – permitted.

So off the Dabaan Department went a-demolishing, with Sharma ji and Gupta ji leading the way in an auto-rickshaw and the rickety bulldozer, a driver and six labourers atop it, following them.

While Gupta ji chewed paan with a vengeance, Sharma ji made sure that the rest of the party followed close behind. Every now and then, he’d lean forward and tell the auto driver to go slow or they’d lose the bulldozer. Twice the auto had to stop to ask for directions – once as close to Dani Limda as the flower shops outside the dargah. And yet nobody realized that they were there. Nobody expected them to come in an auto-rickshaw, even if followed by a rusting bulldozer. They had expected a white ambassador, at least.

The auto stopped at the far end of the colony, on the side leading to the old city. The bulldozer went and rammed itself into the boundary wall beyond. Someone shouted, ‘Oye, has the cutting started?’

Dani Limda was taken completely by surprise. Even Anwar, who had been expecting them and had been keeping watch (Later Munni Apa would say that the colony should have chosen someone more responsible. “He was keeping watch? No wonder my house went down and I didn’t even know.”) did not quite realize what was happening. Not until the boundary wall crashed in and the bulldozer positioned itself in front of the first row of houses. Then, he screamed for his mother.

In the meanwhile, Sharma ji and Gupta ji were having a little discussion over whether to pay off the auto-driver or keep him waiting. “The meter is ticking Gupta ji. We will exceed the allowance limit.”

“Sharma, Sharma! You will cause our death. A pathrao can start anytime in these situations. It is best to have a getaway vehicle ready. Let the meter tick. Also, Sharma, remember: speed is everything. The quicker we are, the less time people will get to realize what is happening. Demolish a few rows before you even look at anybody. Demolish a few more before you talk to them. Actually, talking is never a good idea. We will only get abused for nothing and work will have to stop.”

Thus a few rows of houses were demolished before the parties even registered each other. A few more before they started to argue. Munni apa’s house fell too, a full two days before Sunday.

“You municipal bastards! You couldn’t even wait until Sunday?” She lunged at them, agonized.

“For fifty years we have lived here undisturbed. Now suddenly you decide that this is illegal?” Bhairvi Devi was shaking in disbelief.

“Amma, we don’t know all that. We have orders. The municipality has to lay down underground pipelines. It is all in national interest. If you have any papers, you come to the department and show sahib.”

“Arre, but you’ll have to first give us time to come and show your sahib our papers. If you pull down everything today, what will we go and ask for?”

Gupta ji sighed exaggeratedly. He looked around him. Not much remained of the colony. The bulldozer seemed to have got stuck in debris in the far distance. He glanced at his watch; it was nearly four. He said in his most officious voice, “We will see what we can do.”

The overseers walked over to where the bulldozer seemed to have got stuck in the rubble. “How much longer will you take?”

“This bulldozer should be sold to a kabadi. It doesn’t go a yard without the blade jamming. Do you realize how difficult it is for me? Why don’t you ask for a new machine? With a new machine, I could have done this in less than an hour.”

“With this old, jammed machine, how much longer will you take?” said Gupta ji patiently.

“I am turning back. It can’t do much more than this. Too much rubble. Blade will get spoilt. Also, there isn’t much left – a few houses and the mandir. And I am not touching the mandir.”

“Where’s the mandir?”

“There! By the road. Can’t you see the mandir?”

“That’s a mandir?” Gupta ji scowled doubtfully. “It’s just that you don’t want to work anymore, scoundrel.” Then, before Sharma ji could intervene with any thoughts on duty, he continued hurriedly, “No… but on the other hand, if it is, in fact, a mandir and if you don’t feel proper about this, then come, bring your gaadi out.” And a word to Sharma ji, “Let it be, sir. It’s not good to disturb a place of worship after dark. Plus you know how these people are,” he said, indicating the driver, “very superstitious. If anything happens to him, he will always blame us for making him demolish a mandir.”

Gupta ji found the women who had argued with him and announced that the Dabaan Department would be retreating. In all fairness. And upholding the principles of logical rationality and citizens’ welfare. (But only so far as it could be supported by documentary proof, he warned). “Now, don’t come crying to sahib or you’ll get us into trouble. Come only if you have proper ration cards or meter connections.”

“Don’t think we are gifting back the colony to you. We are only giving you time, and that too because the womenfolk requested it,” added Sharma ji sternly.

The residents of Dani Limda stood rooted. Their houses didn’t exist any longer. There were only piles of rubble. Bhairvi Devi was the first to break the silence. She let out a wail as she ran towards her rubble and sat on it. And with much beating of the chest, recounted once again the story of her last 50 years.

In yet another part of town, in a nattily furnished office, the Housing Rights Group was meeting to discuss the new Urban Policy on Slums. That was when news of the demolitions reached them. The two new recruits were especially outraged: “It’s shameful that we should be sitting here sipping tea, discussing policy, while slums are actually being brought down.”

“I didn’t come here to be an armchair-activist. We should definitely go into the field. Let the agency sponsor the slum’s rehabilitation. Let us provide food, water… whatever is necessary.”

“Go!” said the avuncular, sensitive, regional manager. “Good learning experience for you also. Take Chauhan with you, he is an old hand.” The two new recruits – the lawyer and the graduate in Social Work – drove out in the office van, sincerely, wanting to make a difference.

Sakina texted some friends on the way: “On way to trenches. Slum illegally demolished.” They recalled lessons learnt in class. Made mental checklists, thought aloud. “We’ll have to file a stay petition, first thing tomorrow. I’ll look at whatever papers these people have.”

“I think it is more important to first mobilize people. Explain that a functioning democracy cannot make exclusionary decisions. The people have to know what the urban policy is saying; they have to stake a claim. Make it participatory. The stay petition can only be a small part of the larger process,” said Balram.

“Also give some compensation first, considering how much money the agency has,” said Chauhan ji.

“It’s not about compensation and relief. It’s about participation…”

The office van, too, stopped at the dargah to ask for directions. “Where is Dani Limda?” A very young boy pointed down the road. “It used to be there. I don’t know where it went.”

Sakina and Balram hesitated. It seemed as if the place had been struck by an unusually destructive storm. “What will we ask for a stay on? There is nothing left.”

“Sir, with a little bit of help, they’ll build the huts again. What’s the option? Then we can file a stay,” offered the battle-hardened Chauhan ji.

The sheer enormity of the task at hand, or perhaps their own ineptitude, drew Balram and Sakina to Babu’s tea-stall. There they had several glasses of his special (extra milk and sugar) tea. (Babu, in the meanwhile, was quite pleased with the custom the sudden demolition had brought to his tea-stall. “Look for the silver lining,” he kept telling Chhotu). They discussed possible strategies: “It is important to inform everyone whose house has been demolished that it is morally and legally an untenable act on the part of the government. It has no right to take away their homes without prior notice and without providing alternative housing.” As plans go, this wasn’t, however, a real plan.

Chauhan ji had made progress, though. He had promised everybody office funds for building temporary shelters. “Sahib, if we provide tents and basic ration, then nobody will leave. They will just pitch tents and continue to live on the land. Then you’d be able to file for a stay on eviction.”

“Yes, and if they come back to tear down the tent houses then we shall fight them,” Sakina said. (At this exact moment, Gupta ji, who had just got on to the second bus on his way home from work, suffered a series of hiccups).

A community meeting was called. People stood awkwardly, on unstable ground and listened to a proposal: ‘…So each family must put up a tent where their house used to be. And at the old city end of the colony, where the boundary wall was, we will put up the largest tent – the communal space – for our meetings and for all of us to sit together. We need volunteers from Dani Limda to distribute tents, to also help put them up.”

For the first time in days, Anwar did not feel angry. In fact, he felt quite interested. “Madam, we’ll have it done. You don’t worry. You just take care of the court work.”

Through the night on Friday and the morning of Saturday, the office van plied up and down, fetching hastily stitched white canvas tents. Anwar deftly commanded a growing tribe of young boys from neighbouring areas, as they noisily put up tents. Babu kept tea on the boil. Sakina and Balram puffed at cigarettes, gulped down tea and looked in turn very worried and rather proud. The regional manager paid a visit, congratulated the young blood for their dedication and pledged support. Volunteer staff poured in. Bhairvi Devi whimpered. Bhabhi remembered her home in the village. Munni apa cursed them for not waiting until Sunday. “I had even tied a thread at the dargah. Even that did not work!”

Bhabhi was outraged. “Munni, don’t blame Bade Pir Sahib! You prayed that your daughter’s father-in-law come, and within days he agreed. What more do you want? Don’t blame the dargah.”

“Arre, my purpose was to send her home. I didn’t ask that he come because I am dying to feed him lunch. Do I have to tie separate threads for each part? That he come. That my house remains when he comes. That he settle a date to take her back. And then finally that she actually goes back home.”

By mid-morning on Saturday, the tents had come up. Anwar had got the boys to clean out the rubble from inside the large tent that was to be the meeting place. They had laid out a tattered dari and kept a bottle of water and a steel glass in a corner. Next, they had gone to each family and asked them to bring out whatever papers they had to the ‘office’, where sahib would carefully look through them. Everyone was at work. “If only he would make half as much effort for his own mother,” Munni apa had said wistfully.

Anwar struck up a conversation with Sakina: “You’re doing good work. Will you get paid for this?” And an embarrassed silence later, for the Housing Rights Group did pay decent salaries, he added, “I was just asking. We’ll help you in every way that we can. I’ll also ask my sister to come and meet you.”

In another corner of Dani Limda, the women had gathered on the steps. They were consoling Bhairvi Devi: “Look what you have done to yourself! Crying through the night like this. We’ll build again. The children are hard at work.”

“So now we will live in tents? We’ll give up our houses and live in tents? Two strangers will now tell us how to live in Dani Limda?”

Munni apa was pensive. “You are right. And worst of all, Anwar is quite taken by the idea, which makes it naturally suspect as far as I am concerned. But we’ll see about that later. First tell me what I should do about tomorrow’s lunch? Where shall we seat him? Shall we lay out lunch here?”

“Here, in the open?” said one.

‘Here, in the temple?’ said another.

“Why not host him in that office of theirs?”

“Will they let us?” said someone doubtfully.

“Let us? She herself said it is going to be a community hall. A meeting place. Also, the two of them can talk to him.”

“I don’t know if we should leave him in the company of those two. They’ll never understand these things. Might deliberately say something rude to him.”

Bhairvi Devi approved of this line of thinking. “She doesn’t look like she is married herself. How can she entertain the father-in-law? Most inappropriate choice.”

“And look at what she is wearing!”

“I still think that the community hall is the best option. We will all be there to see that no one is rude to him. Also, let him see that all kinds of modern people visit our colony.”

When Munni apa put forth the proposal to her children, Anwar was horrified. “Amma! There is important work happening there. Please don’t disturb everyone.”

“This is more important than any work that is happening there. Don’t I know? Plain addebazi is what is happening in that office. Rounds of tea and gossip. Now let it be used for some constructive work.”

“Amma, you can’t serve him lunch in front of everyone.”

“Why not?”

“Then at least invite Sir and Madam?”

“Why?”

“Amma, if you are not nice to them, then don’t expect me to co-operate either.”

“I’ll give them tea!”

“Tea, obviously. But at least some jalebis and chana!”

“We’ll see. But tell both of them to behave well. Tell them to talk to him with respect and to answer him if he asks a question.” Munni apa feared he’d ask many. “Is that girl married?”

“Amma! How would I know?”

So Munni apa decided to ask herselfwhen she visited the community hall later in the day. She asked for all pertinent information. “Are you Muslim? Married? Engaged? Why?”

“My daughter’s father-in-law is coming tomorrow to take her home. In our family, we treat every guest well but the daughter’s father-in-law has to be looked after properly. Do you understand? Since my house is gone, I need a proper place to seat him. We were thinking that this place is quite suitable. You two will also get a chance to meet him. He is a very wise man. Owns a pucca house and a shop with two employees. Knows a lot of important people. He is coming especially for lunch tomorrow, do you understand?”

Sakina nodded each time. Later she said, “Balram, man, what are we expected to do in all of this?”

Just after noon on Sunday, dressed in a starched white kurta-pajama, a white fur topi and white leather sandals, the father-in-law arrived in Dani Limda. He was a little surprised, he had to admit, that Munni apa had not cancelled lunch. He was not very comfortable with it in the first place. They’d expect him to bring back the girl, which he would gladly have done. But he knew that she had a temper. He knew that she would only come of her own accord. He suspected he wouldn’t be able to give much in exchange for the lunch.

But he was curious, nonetheless, to see where she’d host him. From all accounts, the colony was totally wrecked. How would the afternoon pan out?

He was received by Munni apa, that boy Anwar, his father and a group of women. One of them giggled foolishly and said, “He brought the baraat and after that he’s come only now. We don’t get to see him at all.” As if a man like himself could afford to idle away time in the company of these very forward women of Dani Limda. He gave a fitting reply: “Do you expect me to come everyday? I am very busy.”

“Of course! He is a busy man. With a shop to run.”

He noticed that he was being led inside a largish tent, where he was escorted to a red plastic chair with a matching red plastic table. They were several other chairs in red and blue arranged in a tight, exclusive circle. With a grand sweep of her hands, Munni apa gestured for him to sit. Then she marched across the room to where a boy and a girl sat on a dari, looking distracted. She took the girl by her arm, signalled to her companion with her eyes and brought the two back to him. “Meet these two. They work in our colony. They are filing a case in the High Court for us.”

“Ah-ha! So she thinks these two novices will impress me. Does she not realize that I deal with their kind everyday?” he thought and firmly set his mouth. He was determined to appear most unimpressed, most disinterested.

The two stood in front of him, hesitant. “Sit!” he said rather majestically. He might teach them a thing or two.

The forward women of Dani Limda were crowding around. That boy Anwar had thrust a glass of hot tea in his hands. The girl, as expected, hadn’t even come to say Salaam.

“So what are you doing about the demolitions?” he asked the novices expansively.

“We’ll file a stay petition in the High Court tomorrow. We were just looking through proof-of-residence papers.”

“But a stay is not permanent. What if they evict two months later? After all, Dani Limda is not a regular colony.” He looked around at the women crowding him and smiled smugly.

“We’ll argue that the colony cannot be demolished without first providing alternative housing to people.”

His face lit up and he grinned. He suddenly saw a justification for his being there without even having to deal with that girl. He could see clearly that if left to these two, the unfortunate people of Dani Limda would sink; he must come to their rescue.

Having so realized, he regarded the lunch with renewed interest. A man enjoys his food so much more when there is no debt weighing on him, when he is able to give back, as it were. Anwar put a plate in front of him and Munni apa served him two juicy, fleshy pieces of gosht. He sucked at each, smiling all the while. “These arguments don’t always work.”

Much later, when he had sucked to his heart’s content and finished all the rice and chana, he first belched and then said, “Instead of this tent-room why don’t you build some nice place of worship, here? At the very edge, where the boundary wall used to be?”

As the two looked blankly at him, he explained, “See, normally no one touches a place of worship. If you have a place strategically built, blocking the colony, they won’t be able to get the bulldozer inside. Build a temple or a dargah, and then rebuild the colony right behind it. In a straight line.”

He took a spoonful of dahi and a jalebi. “Have?”

Anwar quickly moved the plate towards Sakina and Balram. They both seemed a little stiff.

Over jalebis, he continued to convince: “See, they didn’t touch that temple, no? Only problem is it wasn’t built well. Lots of room for the bulldozer to move in.” Looking at Sakina, he asked, “Are you Muslim? Haan, build a small dargah then. Best.”

Anwar looking embarrassed bent forward and whispered something into his ears. He in turn, looked at Balram and said, “Or build a temple. I am not suggesting anything. All I am saying is build in a straight line.”

“We already have a temple. Why should we have two temples? We will establish a dargah.” Munni apa decided to take matters into her own hands.

“It’s your choice! Only problem is that a dargah is not a foolproof guarantee during a riot-situation. In ordinary circumstances, yes! With a temple, you’re safe forever.”

As a full-fledged debate ensued on the merits of this argument, he felt a rightful claim to his third jalebi.

“What do you say?” Munni apa asked Bhairvi Devi rather pointedly.

“Why ask me when you have already made up your mind? As it is I have been moved to the sidelines,” she shot back.

“If it’s a dargah that Mujib will have a place to sleep. And Anwar can become the mujabir. He will be the keeper of the dargah, like he is looking after this hall now. Let him also earn some money,” she said in a conciliatory tone. Munni apa was liking the idea, it seemed.

“The main dargah is called Bade Pir Sahib ki dargah. We’ll call this one Bale Pir ki dargah. People can offer chadars every Friday.”

“Don’t wait until Friday. Start tomorrow. Mondays are also very auspicious. Of course, you can have a bigger ceremony on Friday.” The father-in-law had finished eating now. He looked around at the crowd with some satisfaction, as one who had just saved the day is wont to do. And all this without having to even face that girl.

As luncheon drew to an end, there was sudden tension in the air. The main purpose of the visit had still not been achieved. The women nudged Munni apa who looked expectantly at the father-in-law. As far as he was concerned though, he had already repaid in full what he owed them for lunch. He was making to leave, when she suddenly accosted him. “Salaam! Did you enjoy the lunch?” she asked sweetly. He turned sharply towards Munni apa and away from the girl and said rapidly, “I’ll send Salim on Wednesday. He will bring her home himself. Send her by evening.” A cry of joy went up in the air. Bhabhi said a quiet prayer and blew into the father-in-law’s face. She gave Munni apa a look, rejoicing in the triumph of the dargah and the comeuppance of those who had doubted it.

But spoilsport that she was, the girl looked defiantly at her father-in-law and said: “Not on Wednesday. I’ll come after the first Friday Urs of Bale Pir. Send him on Friday.” He merely nodded. The crowd of women saw him to his rickshaw, which was parked just outside the tent.

Anwar had stayed inside with Sakina and Balram. His sister had been seeing her father-in-law off. As the rickshaw left, she loudly called out to him and cackled, “Wrap up all this now. Salim’s abba has sorted everything out, hasn’t he? No need for all this tamasha.’”

The women laughed too.

Anwar turned red. “Arre chal! How will you have a dargah without a mazaar?”

Sakina muttered confusedly to Balram, “But we cannot allow this. Public spaces must be kept secular…”