Rethinking Aurangzeb (Excerpt from a novel in progress): Parvati Sharma

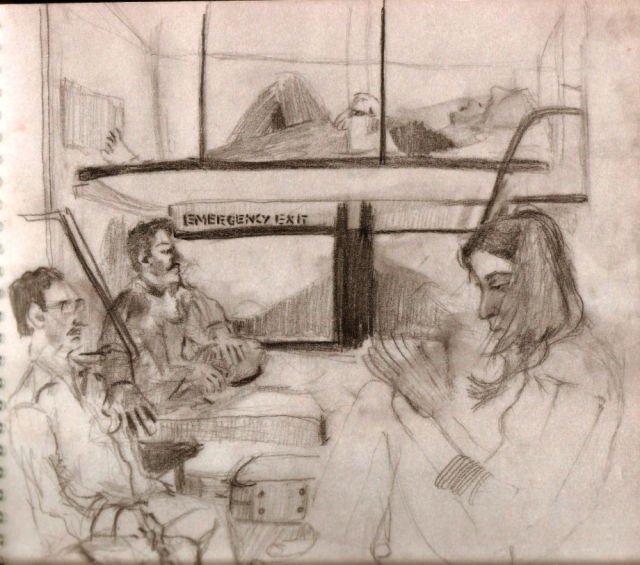

Art: Samia Singh

Brajeshwar was tall and he was thin, a bit like chewing gum, and when he sat in cramped spaces like overfull autos and the backs of buses, his knees would reach his chin, itself over-long, much like his face. His eyes, even, appeared stretched – or drooping perhaps is the right word – extrapolating forever downwards like a dancer’s shadow or a financial whiz kid’s deft felt-pen markings on a graph.

About a year after Brajeshwar became Mrinalini and Narayan’s upstairs tenant and they became friends, he began to date Koel whom he could, given the sheer music of their names put together, have married. But he didn’t.

They were sitting in a crowded bar, the kind that college students and journalists go to. “So Aurangzeb,” said Brajeshwar, lightly turning his glass to melt the ice against its edges and taking a small sip, “he met this girl when he was passing through Burhanpur, which is no place now but it used to be madly important at the time because it led to the Deccan and the Mughals made it a second capital, almost, except,” he placed his glass on the table and slid it a millimetre forward, “by Aurangzeb’s time it was going into some form of decline, so he wasn’t actually made the governor, unlike his father and that generation, you see, and Aurangzeb was actually just passing through, on his way to Aurangabad, but he didn’t get there for months because of this girl. Something-Zainabadi, because you know she was from Zainabad – oh, Hirabai, Hirabai Zainabadi. But anyway, Zainabad is this town across the river from Burhanpur – which is now, by the way, a blossoming red-light area for punters along the border – but anyway, so Zainabad, or Jainabad as it’s called in these ignorant times –”“Braj!”

“What?” He raised his eyes to the table and saw before him: tattooed Koel, long-nosed Narayan with an arm hanging lazily off Mrinalini’s shoulders, ditzy and freckled little Archibald. “What?” Eight eyebrows arched. “Well OK, but these things are complicated you know. So Aurangzeb, he passed through this declining hub and he saw this girl. And here narratives part ways because maybe she was his not-so-important and kind-of-like-that-guy-in-that-book, Heep, Uriah Heep, rubbing his hands together sweatily to curry favour, you know, married to his aunt who was quite fond of him and also a blood relation, so that…” he took a breath that matched the rise of Mrinalini’s eyebrows, “she was his uncle’s favourite concubine. Or maybe she was just one of the dancing girls in the harem. And then some accounts say he first saw her in the Ahukhana which is –” and Braj inclined his head to the left and raised an unlit cigarette to his lips, “I don’t want to bore you, but that’s where Mumtaz Mahal was first buried.”

“Isn’t that…?” said Archibald, Aey-archiecomic! from JNU, where none of his many helpful friends could quite understand what he was doing.

“Yes,” said Braj, satisfied and signalling to the waiter for another round. “Shahjahan’s Mumtaz. Died here, 16-something-or-other, oh 31 – 1631 – in the summer, giving birth to her fourteenth kid, supposed to have been screaming in the womb, rather ghoulish actually. So yeah, they buried her here, in this hunting ground – it’s called the Ahukhana, derives from something Farsi, ahu-shahu – then they dug her up six months later and took the skeleton back to Agra where again they dumped her somewhere until years later she moved to the Taj where,” and now he lit the cigarette and pointed it at Archie, “people like you get to pay a fortune to, you know…”

“A fucking fortune,” said Archibald and Koel rolled her eyes and said, “Braj, if you’re telling this story, can we get to the point please because I have way more important stuff to talk about.”

“Oh no,” said Braj, “Sweetie, this is the fate of the nation we’re discussing here, your insane boss, in comparison, she’s like, you know, those things they do on email forwards where they show you how small the planet looks in comparison to the sun and then the galaxy? Like that.”

“Shut up,” said Koel and silent long-nosed Narayan raised his glass and drained it. “And ants,” he said.

Braj squinted dramatically. “Yeah. Ants.” He felt a surge of alcohol in the back of his head. “Talking of which, next story, I’ll tell you about this Dalit kid who came to me all weepy the other day wanting to know if he should tell his girlfriend –”

“Oh for fuck’s sake,” said Koel, and everyone else except Narayan lit their cigarettes and a temporary change of subject was thus signalled.

Brajeshwar, ably supported by Archibald, encouraged Koel to leave her job if she hated it so much and she said, “And where’s the rent going to come from then?” and they said, “Rent always makes its way to the needy” and Brajeshwar added, “Baby, don’t you worry about money” and blew a straight line of smoke up at the ceiling as she rolled her eyes and thought, for the first time that evening and the third time that week, of breaking up.

Brajeshwar didn’t help matters when he said, “So if we’re quite done with that, shall I finish my story?”

But now, though still keen to reach his punchline, Brajeshwar felt the beginnings of a small knot in his stomach. It made him wait, as they picked at the remains of honey chicken and crispy lamb, at leftover capsicum and soft, translucent curls of onion, it made him wait for first Archie and then Narayan and eventually even Koel to be surprised by the silence, to turn to him and say, “Well then, what happened?”

But when he resumed his story, Brajeshwar heard it grow flat in his own ears, its curious magnificence from a few moments ago entirely spent. “Well nothing,” he said, trying to get into a stride, and “Nothing?” said Koel at precisely the wrong moment, in precisely the wrong way. “I thought it was life and death for the country.”

“If you would only listen,” said Brajeshwar, but he felt himself, as he felt himself so often, give up. The story turned upon itself, going inexorably into lockdown, wrapped around its own eyes, its own mouth, no longer a blaze but a blob.

“Go on, then,” said Mrinalini, encouragingly. It seemed to Brajeshwar that he detected a fellow-feeling in her tone, a kindness that almost brought tears to his eyes. “What happened with Aurangzeb and the Hira, the girl? Did they fall in love?” Brajeshwar smiled a slow, tired smile, as if to suggest that the troubles of this world were far greater than those, amorous or otherwise, of the declining Mughals but, when she touched his hand, he did speak.

“Well, yeah,” he said, draining his glass, “I guess, well, they did.”

“Did they get married, then? Did the uncle revolt?”

“Don’t be coy, Braj,” said Narayan in that way he had – sleepy, imperious, sometimes almost cruel – and this might have ruined the moment entirely, but then perhaps Koel sensed it too, the weight of the story in his gut, its silence, because she said, “Oh come on. Even I want to know what happened, now. Just tell us Braj!” Or perhaps she sensed nothing; perhaps what she did was glance at Narayan, still smiling his sleepy, imperious, almost cruel smile, in a way that made Brajeshwar blink. But then: another measure of Old Monk was poured into his glass and, in the giving of instructions about ice and soda, in the pleasure of a fresh drink, Brajeshwar seemed to recover his humour.

“There was no revolt,” he said, “how’s that hand-rubbing old uncle going to revolt against a Mughal prince? Of course there was no revolt, except maybe in Aurangzeb’s mind, because he was totally falling in love with this girl, right? And she’s a concubine, she’s someone else’s concubine, and she’s Hindu obviously, and she’s not in love with him. She’s giving him no patta, nothing; and he’s just mooning all over her and he’s never going to cross the river and assume his governorship, and who knows what the Deccan will get up to.

“But the thing is, Hirabai, she’s being cold and cruel not because she doesn’t love Aurangzeb,” (unthinkingly or not, Brajeshwar addressed himself almost exclusively to Mrinalini) “Because he’s being super charming, he’s pursuing her in the Ahu-khana, running around trees with her, literally. And she’s worried he’s just not that serious, you know, that the infatuation will pass and next thing she knows she’ll have neither uncle nor the nephew, and that will be pretty much the end of her concubining career. So…”

Braj leaned forward against the table, into Mrinalini’s eyes, willing the story to end. “So….”

Mrinalini glanced at Narayan. Did she smile? Koel drained her glass, jogging Archie’s elbow in the process; a drop of beer fell out of his glass onto the table.

And now, somehow, he did not want to tell them the ending at all. He did not want them to know. It was not so much that he thought it would be wasted on them, just that he didn’t want to part with it anymore.

“So…” said Brajeshwar for the third time and they all laughed. They all said it, “Sooooooo…!”, “Seeeuuuu…!” “So-H!” Narayan laughed till he hiccupped. “Sooooooo!” they chanted, “Sawwwwww!”, like children playing at being aeroplanes. Archie snorted a little beer through his nose and coughed into a paper napkin. “Oh god,” said Koel, wiping the tears from her eyes, “Go on, just finish the story, Braj, I beg of you!”

Brajeshwar looked at her and grinned. “So!” he said, and they shook their heads and held up their hands in surrender and ordered a final round of drinks, laughing, before the bar’s happy hours could conclude.

When they left, their laughter rose above Defence Colony’s hybrid market and their cigarettes burned into their fingers and rolled to the gutter and wrapped in muck, died. They walked, all five of them, half-off half-on the footpath, waving at autos for Archie, then tucking their hands into their armpits against the cold, and Narayan turned to walk back and he said, “Then? Brajeshwar,” – using his full name, laughing it out – “aren’t you going to tell us what happened at the end of that story, bhai?”

Koel giggled, unsteadily; Narayan patted her on the back, Mrinalini patted Brajeshwar; Brajeshwar said, “Kindly fuck off”, not quite sure to whom; Archibald laughed as the autos started to line up before them. In a moment, Archie returned to JNU while Koel and Braj sat silent and uncomfortable in the back of Narayan’s car. At home, he would not say a word but just poured himself another drink, and then one more and then he climbed into bed and put a heavy arm around Koel, pressing himself half-heartedly against her. But she had her eyes closed and only wanted to sleep, so he climbed out again and put on some music on the computer and passed out on the bean bag.

What with both the music and the lights he’d left on, Koel could not sleep. Nor, somehow, could she bring herself to creep through the room, turning off switches and pulling out plugs. As the night wore on she developed a headache and a searing thirst.

It wasn’t quite six am, still dark but the birds had begun to sing, when Koel walked out of the house and found the front gate still locked. Never had she felt a keener longing for her tiny, tidy, freezing hostel room. Never had the thought of her own pillow brought tears to her eyes. She climbed the gate, tearing a hole in her jeans and her left thigh in the process.

They met again, of course, and they talked and they fought. But never again did she feel a more profound relief than when she paused, ever so briefly, to suck in the cold air on the other side of Brajeshwar Jha’s rusty, sharp-edged, paint-peeling gate, wondering where she should go get a tetanus injection.