A Counter-Enlightenment of Sorts: Purushottam Agrawal

(In conversation with Giriraj Kiradoo)

Pratilipi

The popular opinion about the ‘event’ (‘honor killing’) is almost consensual on two things. One: its geo-cultural location can only be a village (irrespective of the actual geographical location of the incident). And two: such acts are, by default, a ‘sign of the medieval’. Your book on Kabir, Akath Kahani Prem Ki contests the mainstream mythology of all things medieval. Would you agree that ‘honor killing’ is essentially, obviously ‘medieval’?

Purushottam

In the first place, it has nothing to do with the village as such and everything to do with caste. It is not village or religion honor killing, but the caste honor killing, where ‘honor’ is taken to mean the authority of the caste elders and control over the sexuality of human beings, particularly woman. Now, in a scenario where the idea of caste has been validated as the marker of identity and the tool of mobilization, how can you expect people not to have a renewed surge of ‘loyalty’ to honor and space of caste. Mind you, this validation is operative not only across the political spectrum, but across the intellectual spectrum as well. So much so that a recent comment, obviously trying to be politically correct, described these murders as “Hindu” honor killings, instead of what they are—plain and simple caste honor killings. The girls and boys are killed not because they have married outside the religious fold, but because they have violated the caste norms. But how can you say something unpleasant about caste and its mechanisms without sounding politically incorrect? So let us call the phenomenon by a convenient name, and what could be more convenient than to label it “Hindu”. Interestingly, no ‘honor’ killings are reported from Gujarat—which is supposed to be the strongest turf of political Hindutva.

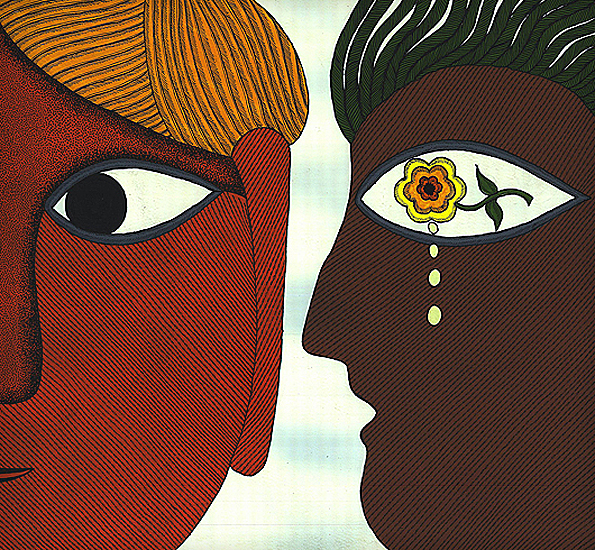

So far as this phenomenon being medieval is concerned, let me just say that caste as we know and see it today – i.e. a reified, stagnant and dominant structure – is actually, largely, a colonial construction. In this sense, these killings reflect the colonial avatar of caste. It is ‘medieval’ only in so far as it reflects the resistance to the attempts of underlining individuality through choice in love. This has been the core issue in any tradition trying to transform itself, trying to make it more accommodative of individual choices. Like any tradition, Indian tradition has also been talking to itself as it were, and one part of it has been medieval in denying space to the individual and to the wisdom rooted in experience, while the other part of the same tradition has been reflecting the articulation of individual’s space and attempts to reinvent social norms. So, medieval is not synonymous with tradition per se, but with a certain position within the same tradition. The same is true of the category ‘modern’.

Pratilipi

But it has been argued that this ‘Counter-Enlightenment of sorts’, as you prefer calling it (rise of religious fundamentalism, censorship, the growing cult of collective identities and their discourses…), is perhaps more directly an outcome of the way the present form of global capitalism is operating in the Third World, no?

Purushottam

It works in many complex ways. Capitalistic globalization (which seeks to globalize the capital, while restricting the global movement of labor) certainly has a role to play, but equally important are the male chauvinistic fantasies going in the name of ‘preserving’ this or that tradition. All such perverse ideas of preservation are rooted in the perennial male chauvinist obsession with ‘keeping woman in place’.

Then, there are ideologies rooted the flat, ahistorical, fundamentalist readings of various religious traditions. The complacent acceptance of violence as a means of making a political point has also contributed to the situation. The worst part is actually played by those intellectuals who discard the idea of universal human values, even in the realm of possibility, and naturally end up overtly or covertly justifying all kind of nonsense—provided it is perpetrated by their favored ‘identity’ or ‘politics’. That is why the idea of rule of law has become such a casualty, and that is why the caste element of these killings is sought to be replaced with adjectives like ‘village’ or ‘Hindu’.

It is the amalgamation of all these factors which I call the ‘counter-enlightenment’.

Pratilipi

There has always been a sweeping demonization of the non-urban in the modern/utopian ideologies and state edifices. The (Khaap) Panchayats have become the contemporary symbol of that. Are these Panchayats nothing but killing machines? Is there any possibility that we could do more than passing on an easily available moral sentence? This seems ethically more pressing, since we have also witnessed that those on oath to fight the ‘backward and the regressive’ can very easily justify genocides in the name of the modern, the progressive and the scientific.

Purushottam

My favorite metaphor has been the ‘guests of culture’. We sometimes act as apologists of every retrograde practice to prove our rootedness, and sometimes condemn the whole of the indigenous tradition as if we are standing outside it, and express our gratitude to colonial masters. There has been no engagement in a spirit of dialogue. We can only teach ‘them’ or ‘glorify’ them, both these attitude emanate from the colonial condescension. A dialogue on the other hand, besides having the self-confidence of saying something important, is willing to learn as well. By the way, on the English language TV channels the ‘liberal’ intelligentsia were forced to say a thing or two in ‘broken’ Hindi (and these were not those who came from non-Hindi speaking regions of the country) as their opponents representing the ‘Khaap’ sensibility could neither understand nor speak the lingua-franca of the educated Indian, particularly of those who are so eager to ‘change’ society. This also, to my mind, was an apt metaphor of the peculiar relationship we, the intellectuals, as a class (or shall we say as a caste!) have created with the larger community.

Pratilipi

It leads us to the perennial modern dilemma about the pre-modern ways and selves. Is there no way beyond the terrible axis of teaching or glorifying? The underlying violence of both is very explicit and stands decoded now. We can’t deny the fact that the liberal democratic state has failed to respect the rights and reservations of the ‘non-modern’ communities. Is there a hidden punishment at work? A punishment for ‘their’ not conforming to ‘our’ needs and demands?

Purushottam

I hope my response to the previous question indicates the “way beyond the terrible axis of teaching and glorifying”. The Khaaps and other such institutions are not just killing machines. If they were just that, they would not be effective even as killing machines. These and other such bodies actually represent a living and very effective system of collectivity and mutual support—and that is precisely why—of ‘discipline’ and sometimes even of downright persecution as in the instant cases.

So, the question in the long-term would be—do the human beings need such systems? Hopefully, everybody would agree, they do. Therefore, the most fundamental question is that of evolving a public sphere wherein the issues involving the norms of social conduct and the individual space and choice could be addressed and new norms and new roles for collectivities and individuals could be non-violently negotiated. Such negotiation can also, in fact does, lead to the emergence of new collectivities and support structures. The older forms of the same have to make way for these new forms. After all, hardly anybody is ostracized these days for choosing an innovative profession or for settling abroad. There is nothing sacrosanct about the so-called modern or pre-modern systems of collectivities.

The communities have a right to their ways, but not beyond the agreed matrix of social norms and laws. A community can have its rituals and ways, but it has to (as a community) recognize its limits and stop insisting on transgressing the rights of individuals. The modern, and for that matter, even pre-modern state can not and should not act as mere dispute-settler between the primordial or given communities. By the way, the Dharmashastra (i.e. legal) discourse in the so-called medieval period of Indian history had made this point amply clear to the communities as well as to the possessors of political power. As you are aware, I have briefly discussed this development in my book Akath Kahani Prem Ki.

The point is that, to evolve and implement the laws is the exclusive preserve of a state, and a democratic state is one which can be held accountable on the parameters of democratic values—not just on those of appeasing this or that community. The problem with the states that have evolved out of colonial modernity is that, having lost the organic relation with the traditions of various communities, they become either diffident and complicit or insensitive and arrogant. This is true of a large section of the intelligentsia as well. The basic issue, once again underlined by these ghastly caste-honor killings, is to get rid of the ‘guest of culture’ status.

Why can’t our hugely popular leaders and brilliantly gifted intellectuals engage the Khaaps in a debate on this whole issue? The answer is clearly known to you as well. For such an engagement, you will have to do a basic rethink on all your ideas of Indian society and traditions. You will have to have a first-hand knowledge and an organic feel of the self-struggles of tradition. You will have to have courage to lose the ready-made social and political support bases.

That seems to be a tall order.