The Bahuroopiya in a Bhoolbuliya: Priya Sarukkai Chabria

Rupture and Rapture

The processes of creativity fascinate me as much as the act of writing itself. What are the transformations occurring in the writer’s imagination and persona that make for a spell of writing? How can this be sustained? Is there another, less explored aspect beyond or beneath the pull of creative expression that propels one to write? Such questions led me to propose – for the recently concluded literary salon – the subject Translating the Self. This, in turn, got translated, through Dr. Alok Bhalla’s interrogations, into The Self and Its Translations as our ideas combined and changed to offer a vaster interpretation of the originary concept.

My explorations are, first, around how the writer translates her ‘Self’ through the play of multiple forms and strategies to make an artistic creation. From here I move to some of the ways the concept of translation is negotiated in my writing.

The “I” of the writer opens outwards and translates through a crucible of words and the via media of literary invention into a multitude of personas, fictions and forms. In this process, the writer’s everyday “I” with its nama-rupa-kriya –name-form-activity – is forgotten. The emergent writing Self is a bahuroopiya, an acrobat in the bhoolbuliya of its own creation, wandering in a labyrinth of solitude and a maze of forgetting and remembering – for it has forgotten its everyday self in order to remember other ‘selves’. Perhaps we write and translate ourselves in part to flee the constrictions of the “I” and in part to flow with the writing self on its flight of exploration. This bahuroopiya, a shape-and-identity-changing entity, is in constant flux as it attempts to fix form, tone and texture through the irradiating depth charge of language. There is an inherent contradiction in the self needing to maintain continuous mutability in order to position and assign form to aesthetic compulsion.

Marcel Proust was possibly considering this nebulous and risky experience when he wrote that the writer is a person who “is blessed with a blurred memory of truths he does not know”. The point here is that the writer knows such truths exist – just beyond the pale of the known and its shadow. Therefore, each act of writing is both:

an act of worlding and

a returning to the “blurred memory” of truths not known;

each session of writing is both

an act of faith towards the outer world as well as

an inner descent into the Self.

The process, being simultaneous and contradictory, yields a third possibility that I seek, even as I invite each reader to actively participate in re-making my work in her or his translated understanding.

*

Richard Ford stated something profound on why we write – and translate ourselves. He said it is the attempt to, “pay reverence to art’s sacred incentive – that the whole self, the complete will, be engaged”. If this, indeed, is the thrust of artistic creation it is necessary to lay out ideas of how this process comes into being.

Here, it is perhaps useful to invoke Bharata’s Rasa Theory of Aesthetic Rapture that insists on the participatory presence of the receiver/reader to ‘complete’ the work of art. That is, another’s presence needs to be involved for the worlding of meaning and beauty.

To complement this argument, Anandavardana’s concept of dhvani or overflow of significance from an artistic work should be recalled. Anandavardana wrote: The true import of poetry (that stands in for all artistic creation) is when sympathetic appreciators have turned away from the conventional meaning (of the work)”. Three concepts collude: turning away from conventional meanings, the active interaction of sympathetic appreciators and true import of art emerging. I propose that this true import of poetry/art may well be the attempt by the artist to reach the “blurred memory of truths not known.” There remain the twined concepts of the sympathetic appreciator and the need to turn away from conventional meanings. Turning away from the conventional meaning of ‘another’ to signify someone else, I suggest what if this ‘another presence’ is interpreted to include the artist’s everyday self?

This transposition implies that as we write the passing, as we attempt to translate ourselves for readers, we are also, simultaneously, trying to catch the dhvani of our everyday selves for we have turned away from its conventional interpretations of nama-rupa-kriya. We therefore become our own “sympathetic appreciators”. In this light, the arrogant exclusivist phrase “I write for myself” takes on another connotation, a deeper and more inclusive shade. Perhaps, through writing, the Self seeks to uncover the everyday self beyond its conventional sense – and taste this dhvani.

All creative acts invite the process of tirobhava – the play of veiling and unveiling. In this process we may glimpse the lurking self that holds the oppositions of the everyday and the writing self. I suggest this is “the whole self”. This is attempted to be recovered, however unconsciously, even today, as response to arts’ “sacred initiative” when we translate ourselves into work.

*

Disparate art forms have shaped the aesthetic structures of my work and it seems as if I’ve often located my ‘self’ through echolocation, sounding off from various art forms.

Ekphrasis

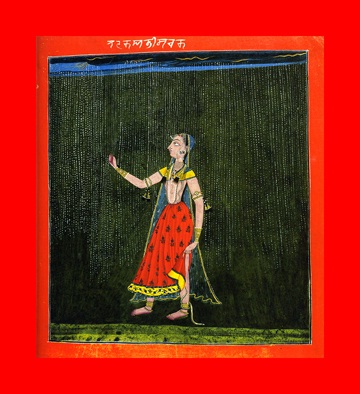

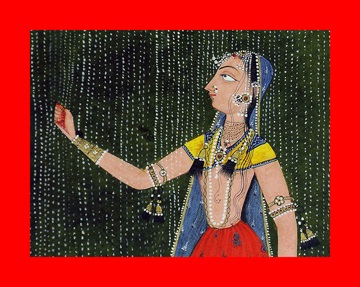

Fireflies was a stage production with images of miniature painting, Bharata Natyam and poetry in English. As a work, Fireflies was an exploration of ekphrasis and the Sanskrit ashta nayika concept. My sister, Bharata Natyam dancer Malavika Sarukkai, and I collaborated to “re-paint” inspiring miniatures as dance and as poetry. Each of us translated the miniatures – within the frame of the ashta nayika grouping – into our own art forms.

(Courtesy Kamala and Jadish Mittal Museum)

The image is of an abhisarika nayika, done in the Basholi style. In Sanskrit poetics, this nayika or ‘heroine’ bravely ventured out of the home to meet her lover. I was struck by the depiction of the rain – as a curtain – that the woman parted. Surely there was more she was parting, and passing through. The poem[i]:

Seeking

The nayika says:

I know it is now time to part.

To part the wind, the clouds,

to part the rain and walk through

on my desire, clear as lightning, forked.

And yet, wrapped in cloud, gripping

the rain, I hesitate.

It’s the rain in my veins that rises red,

steadily, in my throat.

This thrum that grows.

The night is dark.

The lightning so fierce.

Translation as Inversion

From love to war; from ekphrasis to inversions. I wrote a series of poems called Songs from Babylon and Persia on the conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq[ii]. I am interested in how the play of time, place and historical contexts shapes poetic techniques and inform the work, translating earlier concepts, and with it, form and signification.

Songs from Babylon and Persia are after 2BCE –2CE Tamizh Puram poems that praised war and bloody sacrifice, named historical personages such as ruling kings and chieftains. My poem is a conversation between two pi-dogs Salma and Imrana who are sitting side-by-side on the streets of Baghdad shortly after the London underground bombing. We eavesdrop on their conversation.

Salma, pi-dog of Baghdad, says:

Americans are kind.

They leave blood on the streets

for us to lick,

and morsels of human flesh

stuck

to charred clothing.

They return us to our ancestors:

Wolves.

Salma’s friend, pi-dog Imrana replies:

You don’t hear and see so well

ever since the bomb went off in the neighborhood

dump where you had littered

six pups,

one-eyed, one-eared, scar-faced Salma.

Listen:

I’ve heard

the scene of feasting is shifting

overseas

and underground,

in tunnels long and deep.

And that the bombers talk in a language

we can understand, so to speak.

I’d trot there myself for the spread

if it weren’t that I lack

front feet.

Liberal Borrowings: Translations from sci-fi cinema, the historical and the Panchatantra

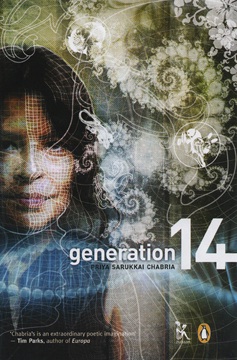

My recent novel, Generation 14[iii] is a speculative fiction set in the 24th century; it is an ‘amnesiac’ novel with political overtones in that the characters, having forgotten the subcontinent’s plural histories, lack a sense of identity (self) and therefore moral responsibility. They live in The Global Community where possessing memory is a punishable offence. The Global Community is an oligarchy ruled by Originals – who comprise the gene pool, Superior Zombies – the militia and administrators, Firehearts – the poets of their society who are used as interrogators and worker clones like the narrator, Clone 14/54/G. She was cloned from a writer and suddenly begins to have ‘visitations’, remembrances of story fragments set in the subcontinent’s plural pasts. This puts her at risk.

The historical and speculative fictions are two sides of the same coin; both are contemplative genres. I employed both in Generation 14. While the embedded stories draw from folktales in that they give voice to the animal world to reflect ‘the human condition’, I drew my speculative fiction galaxy from popular sc-fi movies — Blade Runner, Star Trek, Star Wars, Zardoz, Metropolis

Part One: The Cell

1.

I requested permission to visit the local Exhaustive Organ Transplant Cell where my Elder’s tissues are stored. At the terminus I identified myself: Clone 14/54/G. ‘Permission Granted’ said the computer and the doors slid open. As I waited for the ‘remains’ to hover before my eyes I wondered what drove me to this sterile, silent vault. It was an uncharacteristic, impromptu decision and this troubled me. I already had knowledge of the contents; what further could I gain by actually seeing it? The air was an intense turquoise and smelt of bimedi-nixochorohplly. After 6.21 minutes the transparent organ-sheath had not still materialized. I queried the delay. The response was, ‘Access recently granted.’ ‘To whom?’ I asked. ‘Clone 14/53/G.’ I repeated my identification. ‘Processing request’ replied the computer.

There she was, what was left of my Elder. Labeled, packaged in frozen plasma and dangling beyond the touch-proof barrier. Her feet were large, the little toes squashed, like mine. I bowed my head though I don’t know why I did this either as I spoke the routine words of thanks we repeat on our cloning ‘birthdays’. ‘Clone 14/54/G wishes to pay tribute to my Elder, Clone 13/ 15/G. We are the same and we give thanks. Long live our global community.’ I remained silent and staring till the sheath was called up.

I must have remained head bowed unaware of the three ‘Visit terminated’ warnings that the computer sounded before it sent a crackle of electricity in front of my face. This fizzed my hair. I withdrew before stronger bolts followed. Walking out I saw a Fireheart being led into the vaults by a Superior Zombie. It was an odd sight. Firehearts are bred for purposes of interrogating the living, not querying the dead. Unless there is a living brain in these vaults that has refused to yield its secrets . . . For Firehearts are the poets of our society, and as poets, cannot speak lies. They make excellent investigators for they will not give up till they are satisfied with the answers even if their antennas burn up in the attempt and they writhe and perish.

At my workstation I performed my job till time up. I knew nothing would interfere with my working; as a clone I am mistake-proofed while on duty. This is no small relief. The visitations begin later, when I am alone in my cell.

Last evening as I was swallowing my mineral supplements I was engulfed by coldness and a sense of verticality. I was stuck on a wall and witness to a ‘transaction of flesh’ below between a man called Marco Polo and a woman called Love’s Sweetness. He was a merchant headed for China, his ship harboring in old Kochi on India’s southwest coast; she was the town’s most renowned courtesan. It was strange. To begin, they were of different colours, not like us, standardized. He was a patchy brown-pink and she was — there’s an ancient word for her skin colour, I know it– she was ebony. It was a long ritual, and confusing, that now returns to me.

Yes, I know who I was yesterday: A gecko on the wall of the courtesan’s house. She offers him betel nut and cardamoms and wine and jackfruit and goat meat on a silver platter lined with green banana leaf. He offers her four silver coins. She turns her back on him. She’s directly below me, her face to the wall. He offers five, seven, ten silver coins; he offers her three gold coins. She turns towards him. She removes her upper garment; her breasts are large, the nipples painted scarlet point towards me. Love’s Sweetness insists Marco Polo bathe before he touches her. He is led away. He returns looking less patchy. They play dice and drink wine. She suggests he remove her necklaces. He begins and is entrapped in meshes of gold, his face between her breasts, his hands on her body everywhere. She laughs -it is sweet – looks at me and asks, ‘Good-luck Gecko, shall I begin?’ My tail rises of its own accord and thrashes the wall three times. She removes one pin that releases her circlets of gold; all of it falls to the floor. She removes her clothes, she removes his. She runs her hands over his body while she beats his hands back at every attempt to touch.’ Wait,’ she tells him, ‘beg and wait.’ Marco Polo is flushing and panting, he surges on her. She signals her attendants who bind his hands with a scarf of scarlet silk and lay him on a couch of white satin. ‘ Good-luck Gecko, should I sit astride him or be beneath; or perform the churning? One thrash of your tail or two or three?’ Love’s Sweetness asks. I know I’m her sacred gecko. I want to say three. I raise my tail to strike but there is a fat cockroach climbing the wall; it’s almost within reach. I tense and creep. In my mouth: Frail feelers, crusty thorax, brittle wings, six legs thrashing.

The visitation vanishes.

Translation as departures, divergences, detective work

The next is an excerpt from the poem The Portrait. My approach here was of departures, divergences, detective work and leaps of faith.

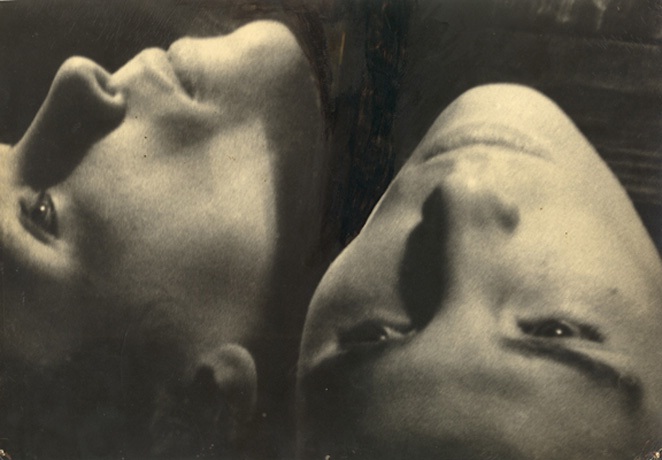

I was invited by the literary journal Vislumbers to respond to photographs – and I chose this by the Spanish photographer Ernesto de Souza who later made art installations as well.

(Photograph by Ernesto de Souza)

As I kept staring at the image I wondered: what is this second head saying? Is it a true reflection or is it a vision — and if so, of what? This poem is not ekphrasis nor inversion or even borrowing but enquiry: into doubleness, and photography, into identity and image-making and the possibilities of translating Self. It involved some amount of literary detective work too.

4.

Two faces, bodiless, wrapped in sooty elements, emerging

twin mask therefore:: twin solitaries. Neither are reflections

but two transparent vases upturned

that show their contents in triangular cones of noses, eyes:: as fluid stone

a myth caught on film/fire. No Janus this, betraying both his faiths, cracked

lightning trussing the heavens but he’s all trusting, immobile, massive

meteorite lost in space. No portrait this, impassive. A dream

perhaps? An imagination of becoming, a man dreaming himself into being

orbiting some singular thought that doubles, doubles. Stone man, strange mineral on a lonely path trailing fire, fleeing, burning up as he invents himself

and his other. He wants no mere mirror image, no gloss or sheen developing from darkness but this: communion with another. Possibly himself.

He dreams his twin in the Labyrinth of Solitude.

He dreams in his solitude like The First One.

6.

Says Plotinus in the Enneads: “the blessed frees

himself from the things here below and begins

his flights into the Solitary”

which, long after, translates as

Paz in In Light of India: he who contemplates sees

himself in what

he contemplates.

which long after, could translate as:

the gaze is always outwards, the inscription is of the other

that one holds or stammers towards

In writing and silence, in the etched image

wrought in solitude:

Perhaps

perhaps

Ernesto says

through this doubled

vision,

this trope, this trompe- l’oeil

this misnomer of image, of identity:

Behold

behold

the other, the world

you hold

in your

image.

Traditional interpretation: one language worlding into another

I’ve begun translating from Old Tamizh, the pasurams, the hymns of the superb 8th century Tamizh saint-poet Aandaal from her second and last work, Naachiyaar Tirumozhi (The Sacred Songs of the Lady). I give below three stanzas that hint at the complexities that Aandaal played with, in terms of (1) myth and mystical insights, (2) her understanding of the environment and the rigours of ancient Tolkaapium poetic requirements and (3) her intense erotic mystical love. It seems to me that such translation requires one to make a supple, sturdy and transparent bridge of one’s self.

1.

Thousand Named, Beautiful, Compassionate, Glorious, Eternal, Effulgent,

Narayana

you are

and also the dark boy

Yashoda’s joy

my playmate

tease

2.

Ruby ladybugs, red drops, flutter through moist sparkle

to alight on languid lush land, like a scatter of blood

under skies rolling, irradiating, like my love for him who

covers me all over, wet

3.

Bring me his garments translucent, yellow as shimmering

pollen through which the dark majesty of his thighs rise

glistening and drape me in his scent

so my every pore is perfumed – then shall I be content!

Notes:

[i] Dialogue and Other Poems, Sahitya Akademi, 2005

[ii] Not Springtime Yet, HarperCollins (India) Publishers, 2008

[iii] Generation 14, Penguin-Zubaan, 2008