Re-membering Woman: Sukrita Paul Kumar

PARTITION, VIOLENCE AND GENDER

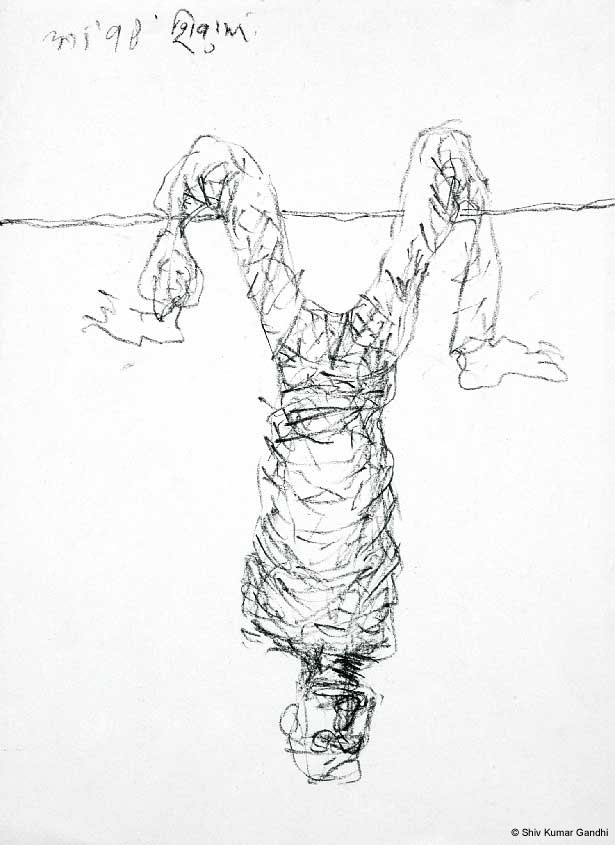

A conscious effort to discern women as victims of the Partition 1947 raises the curtain to the uncontrolled release of a bizarre male violence on the one hand and a nerve-wrecking dis-membering of the female body and self on the other.

“Death may be considered at one level as essentially marked by its non-narratablility, by its rupture of language”[1]. Ironically, it is this non-narratability of death that takes one back to it repeatedly, back to the death of another, to a kind of a death also of one’s own self. The phenomenon of death tends always to remain incomprehensible. Since by its very definition death means a total end and a cessation, it snaps the past from the present. The traumatic violence meted out to the numberless women at the time of Partition demolished all sense of self, existential or social, granted to them by the already rather constrictive patriarchal consensus. If they did not die a physical death, they died many a psychological death. They were too preoccupied rehabilitating themselves materially to be able to strike a mental re-engagement with life all anew. Or they remained stuck in the memory of the harmonious past by obliterating the ugly present and in that denying themselves a future.

An attentive scanning of the fictional and personal Partition narratives of the last few decades with a conscious focus on women protagonists, effectively helps in a sensitive mapping of the inner terrain of the female psyche. Many an aspect of this reality lies under cover of what is otherwise perceived as the “larger narrative” or the “main story”. This paper has woman as its protagonist and it attempts to unearth the complexity of the victim-protagonist who may rise from her ashes heroically to keep her battle going or she may be totally annihilated.

Partition meant mass migrations. Women reacted from the depths of their being at the idea of leaving home. Many literary narratives bring out this anguish. When the entire family decided to migrate, no amount of force or persuasion could make the Amma of Ismat Chughtai’s story Jadein (“Roots”) leave her haveli. “Every effort was made, but Amma did not budge from her place, she was like the roots of a giant Oak that remains standing in the face of a fierce storm”[2]. But then after everyone had left, the giant Oak swayed in distress thinking of her near ones who were in exile and perhaps in a state of anguish. The old lady, “Bebe”, of Joginder Paul Urdu story “Dariyaon Pyas”(“Thirst of Rivers”[3]) carried her ancestral haveli in her mind across the borders. She clutched the haveli in the grip of her hands, as it were, by carrying the keys of the haveli on her person all the time, close to her heart. Krishna Sobti’s Shahni of the Hindi story “Sikka Badal Gaya” too resisted the uprootment from her haveli. The writer poignantly captures the torment of the elderly woman who is pushed into migration when her very identity is founded on home and kinship within that house. To her, discarding this home meant discarding her self.

That is why Amma of Ismat Chughtai’s story “Roots”, is not at peace at all even when she remains in her haveli, because the people who made a home of that haveli, had all migrated. “Bebe” of the story “Thirst of Rivers” on the other hand, has her people close to her but she does not have the haveli she had built up as home; she remains stuck to the past in her mind, clinging to the keys of the haveli, the keys which open no locks now. Sharing her personal narrative with Ritu Menon, Somavanti says decades after the Partition: “Even today there is no peace. No peace outside, no peace inside …I don’t sleep, there is a feeling of being unsettled”[4].

In the normative structure of the society, women are completely identified with their homes and have a strong of belonging. It is not strange then that a woman fixes her identity securely within the framework of her family confined to the four walls of her house. If displaced from such a format of existence, she is shorn of the basic marker of her identity and with that she dies an unnatural psychic death. She uses the strategy of forgetting. But here, one is reminded of some lines of the narrator from Kamleshwar’s story “Kitne Pakistan” (“How Many Pakistans?”): “I am sure that you remember those days. Women never forget anything. They only pretend to forget. Otherwise it would be difficult for them to go on living.”[5] Pakistan in this story becomes a metaphor for the gruesome experiences of Partition. Partition appears as a huge divide, a fissure filled with abysmal silence, forcing the woman into amnesia, a virtual dying to the past.

That is why tropes such as forgetting, discontinuity, exclusion and silencing have been used in the historical as well as many fictional narratives that record the phenomenon of Partition. One of the most disturbing consequences of this has been the invisibalization of woman. The society had to recover them and value the massive chunk of vital human experience lying repressed in hundreds of women, disoriented and alienated due to the wrenching separation from their roots. “Remembering” itself becomes a strategy for relocating one’s self. In the last couple of decades, the countless number of interviews and personal narratives of women recorded by scholars, has brought to the surface what many creative writers delicately presented earlier through long and short fiction. While a personal narrative may be coloured by the blinkers of subjectivity changing over time within the specific contexts of narrations, the writer’s perception may bring out reality more objectively.

It is pertinent that Saadat Hasan Manto uses a Jewish woman in his story “Mozel” to desexualize religious allegiance. Tirlochan Singh is in love with Mozel who agrees to marry him only when he cuts his hair short, as if demanding out of him a person who has the courage to rise above his religion. That in fact could have been in itself the resolution for the crisis born out of the communal strife at the time of Partition. Mozel demonstrates the smart boldness of an uninhibited person free of both religious as well as sexual constrictions – She strips naked and runs, asking Tirlochan to pretend to pursue her and falls – She pushes away Tirlochan’s turban from her body and says “Take away …this religion of yours” before she dies. She is instrumental in uniting Tirlochan Singh and Kirpal Kaur . She dies as if to leave the world to continue with its pretensions. She cannot fit into such a world. Death for Mozel is freedom. Her robustness is presented in sharp contrast with the fragility of Trilochan’s convictions and Kirpal Kaur’s naivete. In the communal conflagration, she stands as a symbol of religious neutrality, as both, an outsider mocking at narrow bigotry and as an insider of the community of lovers, who can take risks and even die to sustain the love between others. The story leaves behind the force of a protagonist who suggests the need for radical reorientations.

What the writer has achieved in this story is a motivation for change. Mozel is a very significant character because her portrayal is testimony of the power of an unattached woman. She is a woman whose existence is not circumscribed by the need for any physical or psychological security provided by the sense of “belonging” either to a religious sect, a socio-political community or more importantly, even a family.

For thousands of people, a crippling happening, it is ironic however, that partition became in some contexts an enabling phenomenon. Compelled by the pressures of the times and the force of circumstances, a great number of women were led into making a big psychological shift. The upheaval of migration uprooted them from their domesticity and they moved to the outside world, wanting to work and once again reconstruct their homes. In her interview with Ritu Menon and K. Bhasin, Bibi Inder Kaur remarks “Personally I feel that Partition instigated many people into finding their own feet” and she adds, “Partition provided me with the opportunity to get out of the four walls of my house. I had the will power, the intelligence, Partition gave me the chance. In Karachi I would have remained a housewife”.[6] Women such as Bibi Inder Kaur demonstrate a dramatic change of personality after Partition. She comes into her own. But she could very well have remained the passive Kirpal Kaur of Manto’s story “Mozel” before Partition, consenting to be a mere object of desire with no control over her predicament.

The thorough shake-up of the society caused by the mayhem of the division of the country disturbed many steadfast notions about religious harmony. The grotesque scenes of violence evoked by religious sentiment were witnessed with shock and bewilderment. A thoroughly communalized outburst of violence, action and reaction indicated the need to question such beliefs and faith in religion that could provoke barbarism. To many, ideals derived from religion and mythology became suspect at some level of consciousness. Women’s roles had been actually determined, sanctioned and promoted firmly by religion alongside the reference to a mythical past within familial and social structures of patriarchy. In one sense, the disruption caused by Partition offered possibilities of a radical recasting of women’s identities. Also, the notion of preserving the “honour” of women as an a priori in relation to their lives sought to be interrogated. One of the predominant forms of violence of one community over the other has generally been sexual assaults on women. These acts have been perceived as acts of dishonouring the whole community.

So entrenched is the notion of protection of “honour” of their women in each of the communities, that women were forced to either commit suicide to pre-empt the humiliation of getting sexually assaulted and dishonoured, or they were actually murdered. Ashis Nandy, Veena Das, Mushir-ul-Hasan and others narrate the bizarre sexual violence suffered by women- their bodies mutilated and disfigured, their breasts and genitalia tattooed and brandished “with triumphal slogans”, their wombs knifed open, foetuses killed, rampant raping[7]– all this male savagery using the woman’s body as an easy object to dishonour the other community. Ironically to save guard their self-respect, the members of the target community too, preferred to kill their women. Literary memory becomes almost a mandatory source for the subtle revelations of some deeply ingrained attitudes operating behind so much of the action during the days of Partition. There are indeed sexual politics operating subtly behind the absence of emphasis on the narration of “pornography of male violence on women”. High politics did record in history, debates about the inevitability of Partition but what was suppressed was, the great human tragedy of the times. The magnitude of this human aspect of the tragedy of Partition cannot merely be relegated to statistics of how many rapes or refugees were witnessed.

The emotionally insulated Lajo in Rajendra Singh Bedi’s story “Lajwanti” is a victim of abduction but she is recovered by her husband who is himself one of the leaders of the group mobilized to recover Partition women-victims and rehabilitate them in their homes. There is an incipient feminist consciousness working within this story. The story focuses on Lajo’s consciousness as she suffers quietly to see how she has been transformed and venerated as a Devi, a goddess, by her husband after she is recovered and they come together after 1947. She is no longer Lajo to him. She becomes Lajwanti, ironically, the one who will withdraw like the “touch-me-not” with any touch.

This connects very well with how Kamleshwar defines the catastrophic moment that is Partition revealed in his story “How Many Pakistans?”: “Alas, Pakistan is the name of that reality which separates the two of us…It is that blank void between our families.”[8] In this case, the void emerges between lovers for whom life could just not be the same. The notion of honour and purity of woman is so deeply internalized that even the spokesman for the rehabilitation of women, Babu Sunder Lal of Bedi’s story cannot come to accept “the defiled Lajo” back into their normal relationship. In a way, venerating her as a goddess becomes a strategy to distance himself from her. The wife in Lajo has to die an unnatural death. Life has to be redefined. Bedi records the popular sentiment in the story “There were some amongst these abducted women, whose husbands, parents, brothers and sisters refused to recognize them. “Why didn’t they die? Why didn’t the take poison to preserve their virtue and honour? Why didn’t they jump into a well? Cowards, clinging to life!”[9] The writer exposes the hypocrisy as well as the callousness of the world of men who denied their women a normal life, either by brutalizing them or deifying them.

It is well-known how control over women’s sexuality perpetrates through male protection of the community’s honour. For their own honour and the community’s dignity, men forced their women to die by providing them with weapons, strangling them, drowning them or burning them. Products of patriarchy themselves, women often consented. Their elimination denoted their martyrdom and their murders completely acquired social sanction, since the act of killing had after all the noble purpose of safe-guarding honour. However, there were women who resisted the imposition of such a death and confronted the possibilities of rape and the stigma of sexual impropriety. Finally, then, those who survived the riots, emerged with a greater existential autonomy. Not only did they accord space to themselves for growth, they also create in themselves the enterprise for independent living.

There was a large number of women who were not “recovered”, women who apparently reconciled to the new circumstance, but they carried within themselves the gnawing sense of the irreparable loss of a perfect past. To get a glimpse of the inner self of such a woman’s mind, Jamila Hashmi’s oft quoted story “Banished”[10] comes to one’s mind. The protagonist of the story is doomed by memory and the inability to forget. The desirable past is unrecoverable. The inner monologue is a recalling of that past which counterpoises itself with the present. It is in the present that she has children from her “abductor” who has actually married her. She reacts inwardly to his mother who addresses her as “bahu” and creates a semblance of order. But this Sita, unlike the mythical Sita, as the story tells us has had to accept “Ravana’s home”. Suspended between her past and the present, she is in fact banished from her own selfhood. This is yet another kind of death seeking regeneration, a replanting! The story ends thus: “Life too flows on, carrying with it, as it always does, the smell of death”.

Jamila Hashmi’s protagonist may have the surface-appearance of an inert object, but the writer catches the throb of her consciousness in the sad monologue that runs all through the story. Her tottering personal identity comes together through her recalling. What is enshrined in her memory is gradually unfolded – as if to recall, readjust and reorder herself in the new context of her children, a new reality and a fresh area for rooting.

In the absence of any customary forms of sharing and mourning available to the victim, Veena Das, as mentioned earlier in this paper, stresses on the survivor’s need to tell her story again and again. The exorcising of the haunt of the past can perhaps be achieved by even telling her story to herself repeatedly. This becomes another device used by the psyche that has suffered from a long drawn dehumanizing process of de/effaced identity. First, she would have to relocate her own being. The permanently banished Sita of Jamila Hashmi’s story has to reformulate herself after she has been wrenched from her own kinship support.

It is in Yashpal’s Hindi novel “Jhootha Such” that Tara’s evolution of selfhood is clearly traced in its own individual capacity. The woman protagonist may indeed come out of the pathological state of mind if she possesses independent inner resources. After having suffered humiliation in marriage as well as outside in society during Partition, Tara frees herself from the taboos of patriarchal family and carves out a career for herself. It is in fact a direct fall-out of her experience of Partition, that a radical progressive transformation takes place in Tara. She gets equipped to take her own decisions after seeing herself through a series of demeaning experiences. She learns to spell out her own destiny and steadfast, perseveres in the pursuit of her selfhood.

It is reported in the “Progressive Education Reports” of how massive projects for the education of women were launched as part of the rehabilitation programmes by the Government of India soon after the Partition. Ironically, in this respect, Partition served as a great boost for the education of women, particularly for the refugee women in Delhi. Education meant more and more career women and economically independent women. In her study entitled, “Partition and Family Strategies: Gender Educational Linkages among Punjabi Women in Delhi”, Karuna Chanana describes how the expansion of social space in the years following 1947, led to a number of cultural re-orientations of the society.[11] Women moved out of their domestic insularity and underwent attitudinal changes as well. Mohan Rakesh’s story “Miss Pal” is the story of a single woman locating herself heroically in a society traditionally dominated by kinship norms. She is not made out to be a Partition refugee but she is a career woman in Delhi living outside marriage with the fortitude of a person who has seen it all – a product of a generation of women-refugees pushed out of their four walls.

Though the Indian Government set up a number of rehabilitation projects for what were called “unattached” women, the state support for Partition widows and single women was certainly not adequate to cope with the problem of the sheer immensity of the numbers of women seeking attention in this context. “A Leaf in the Storm”, a story written originally in Malayalam by Lalithambika Antharjanam captures the fate of such an “unattached” woman, an unfortunate victim of multiple rapes. She is pregnant and a picture of “a bundle of rags crawling up and down, like ghosts let loose from sepulchres”[12]. The story once again, is predominantly an internal monologue, revealing different intensely emotional and reflective responses of Jyoti’s reactions to the baby in her womb conceived in the stupor of her rape by one of the many aggressors. From anger and deep bitterness to the moment when she reaches out to her baby, the movement tells the story of a rape-victim slowly shedding the gory experiences from her consciousness, to give place to warm feelings for the child. The little life, she says to herself “is seeking refuge, stirring its little feet” and feeling the mass of flesh on her belly, ” Oh how warm it is! Did my body give it so much warmth? I hope its looks are like mine….Perhaps I should look at it, its small eyes, once…just once!” [13]

Towards the end of the story, Jyoti’s mind lays her claim over the child. It is as though the child who has given birth to her maternal instincts and the mother in her awakens! Her universe becomes positive and the “dimmed stars beam from the heavens”! The triumph of motherhood of having acquired something, of relating and providing for another life define Jyoti’s life with fresh affirmations. The complex puzzle of living gets resolved with the strength of spontaneous maternal instincts. Not only has the new life been given refuge by the mother, the woman herself acquires a fresh life and sustenance from her pregnancy which she earlier abhorred. It is not as if the violence and sexual assault on her is thus legitimized, but the woman has moved on – the denigrated woman enters the world of positive motherhood rather than getting stuck in the mire of persecutory victimhood. She will soon perhaps be prepared to defy all social norms to safeguard her child and keep the stars shining in the heavens! In this case, motherhood in itself becomes the source of strength for the woman -the experience not coming to her externally but from within, from her own biological existence. The writer, Lalithambika Antharjanam, has in fact articulated the silence of the woman and identified the quiet process of exorcising the rapists from the woman’s mind, the moment she awakens to the biological reality of the baby within her.

The historiography of Partition demands the cognition of claims for personal identity which have been lost in high political discourses. In that, the diversity of individual experiences got homogenized and the intense silences of women remained ignored for a long time. Though women are present in several official and unofficial documentation of Partition history, they have been primarily perceived as objects, not “subjects”. Their experience of Partition is not merely significant for the understanding of their own identities but it also presents a perspective on the socio-cultural re-orientations in modern India.

Women who had lost their husbands and families, had to perforce acquire economic worth. For this they could not remain confined to the traditional norms of behaviour prescribed for widows. The rehabilitation of widows meant suspension of many social constraints on them. The fetters imposed on widows by patriarchy had to loosen to re-assimilate them in the society. A special section within the government was set up to help their rehabilitation and they were referred to as “unattached women” rather than widows. Supported by such an official gesture, these victims of the national catastrophe mustered extraordinary courage and enterprise to renegotiate their mode of existence in the post-Partition scenario. This is not to undermine the tragedy of hundreds of women who suffered irreparable damage, totally incapacitated both physically and psychologically. Manto’s story “Khol Do” is a horrific revelation of a woman who has become insensate after undergoing the experience of multiple rapes. She has inwardly resigned herself to becoming a robotic object. At the sight of a man, even when it is her own father, she makes herself ready for yet another assault.

Banto of Yashpal’s “Jhootha Such”, rejected by her family and husband, commits suicide while Tara takes up the new challenge of survival and does not seek any male sanction for the re-formulations of her life and action. Either there is a total standstill and complete cessation of life, or there is a spirit for complete regeneration! Many men and women were compelled to locate fresh psychic and material situations as a consequence of the disruption caused by Partition.

Elise Boulding’s essay on “Women and Social Violence” published in the UNESCO book, Violence and its Causes (1981), dwells on how the ‘institution of rape’ is based on the definition of woman as object and woman as non-person. With this kind of a perception of woman in the society, the male desire unleashes itself to its utmost barbaric proportions and exploits the mass hysteria of dislocation. The study of the Partition riots with a gender perspective gives an insight into sexual politics as much as communal politics, exposing thus some deeply internalized notions and social orientations. What is demanded in such a situation is a fundamental reordering of the approach of an individual to the Other i.e. the Other of the other community as much as the Other of the other sex. Partition riots demonstrated the ugly coming together of gender politics and communal hostilities.

To salvage the human value of harmonious inter-relatedness, a number of examples are found in literary and personal narratives of women giving refuge to members of the other community at the time of riots. Rajo, in Bhisham Sahni’s well-known novel, Tamas, takes a risky initiative and offers shelter to a Hindu old couple while her own communally-motivated son wants to kill them. Rajo’s decision and its effective execution can be seen as a gesture of courage, salvaging and perpetrating human values. The recording and examination of such incidents stress on some cherished human values upheld essentially by women. This becomes also a significant area for study that can bring out the positive role of women in moments of social crisis. In fact, such findings can give appropriate directions to the Women’s Movement. As Flavia Agnes points out “the women’s movement does not stand in isolation and is an integral part of other social movements. The agenda of women’s movement has to get redefined within the dynamics of social contradictions and ideological shifts.[14]

At the individual level, while for some, the erasure of the violent past from memory was in itself the resolution, for others confrontation with the horror of the past, helped a re-membering of their identities. For the good mental health of the society, the significance of the narratives of thousands of brutalized women cannot be undermined. What cannot be shared through reports, can only be narrativized. The absences, silences and different kinds of psychological deaths of women find voice in these narratives. It is understandable that, of late, historians and social scientists have been closely examining Partition literature in order to rework and comprehend the socio-psychic and political dimensions of the complex history of those times.

The greater the anguish of the woman, the greater the need to make this inarticulatable pain accessible. The consequences of such a large-scale experience of Partition has had to be far reaching and compelling. Women’s Studies Curriculum can bring within its ambit, insights from various disciplines such as literature, history, sociology, psychology and culture, on the theme of Partition with a gendered perspective to help understand some of the cultural re-orientations of Modern India.

The deconstructed, and demolished selfhood would have to be re-membered. The story would have to be told again and again to locate fresh connections, for life to move on, for the hearts and heads to be in their assigned place for directions and resolutions, for history to not repeat itself.

Notes:

[1] Veena Das, “Our Work to Cry: Your Work to Listen”, Mirrors of Violence, Ed. Veena Das, OUP, 1990.

[2] Ismat Chughtai, “Roots”, An Epic Unwritten, Ed. Muhammad Umar Menon, Penguin India, 1998.

[3] Joginder Paul, “Thirst of Rivers”, Translating Partition, Ed.Ravikant & Tarun Saint, Katha, 2001.

[4] Ritu Menon & Kamla Bhasin, Borders and Boundaries, Women in India’s Partition, Kali for Women, 1998, Pg.204.

[5] Kamleshwar, “How Many Pakistans?”, Stories about the Partition of India, Vol.II, Ed. Alok Bhalla, HarperCollins Publishers, Delhi, 1994, Pg. 173.

[6] Menon & Bhasin, Pg. 207, 204.

[7] Menon and Bhasin, Pg.43.

[8] Alok Bhalla, Vol.II, Pg.174.

[9] Bhalla, Vol.I, Pg.58.

[11] Karuna Chanana, “Partition and Family Strategies: Gender Educational Linkages among Punjabi Women in Delhi”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol.XXVIII, No.17, April 24, 1993.

[12] Bhalla, Vol. I, Pg.137.

[13] Bhalla, Vol. I, Pg.144.

[14] Flavia Agnes, “Redefining the Agenda of the Women’s Movement Within a Secular Framework”, Politics of Violence, Ed. John McGuire, Peter Reaves and Howard Brasted, Sage, Delhi, 1996, Pg.106.