Ahimsa in the City of the Mind: Alok Bhalla

Ahimsa in the City of the Mind: Language, Identity-Politics and Partitions

“You have killed a lot of people – that’s about all. Anybody can do that for a while, and then be killed.” – Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory[1]

There is, I think, a close relationship between those who arrange languages in a structure of hierarchy — languages which are assumed to be original, holy, classical, sophisticated and learned on the one hand, and languages which are sometimes seen as mistakes which even the gods can make at times, or as low vernacular tongues which are late arrivals in the human habitat, or as distortions in ‘gender mirrors,’[2] or as irritating murmurs at the borders of culture — and the myths of holiness and purity upon which the politics of ethnic and national identities is based. Thinking about language and identity within grids of power is ethically graceless for it turns others into hostile strangers. It is also dangerous for it transforms our politics into a delirium in which the stranger is always a monster.[3] While the language of privilege available to some gives them the right to inflict humiliations on those who live outside its borders, the idea of an exceptional identity bestows upon ethnic and religious mythmakers the right to debase everyone who is different — and humiliation and debasement as we know can never be enough.[4] Both, thus, deny that the human ability to cultivate a language and to craft a life — any language and any life — gives to each of us equally enormous privileges and responsibilities, and, so demands from each of us courtesy and respect.[5] It would be needless to say that both would dismiss with a contemptuous shrug and an impatient snarl any suggestion that the strangeness of human words and of human footfalls upon the earth are always and already mingled with the infinite variety of the sounds of animals, birds, trees and other sentient beings who share the earthly habitat with them as romantic nonsense which should be confined to the powerless realms of poets, dream-sodden shamans and madmen.[6] An so, unfortunately, both continue to mark out their spaces with such fanatical singularity that one begins to hear, beneath the word, ‘territory’, fearful echoes of words which have come so frequently to define our experience in the world in which we live at present — ‘terror’, ‘terrier’, ‘tears’ — establishing, thereby, our kinship more with the ferocity of animals than with our ideals of reason; making us, not artificers and seers of grandiose things imaged by the muses,[7] but hard-bristled, sharp-fanged, knife-clawed creatures with merciless fires in our eyes.

I want to narrate two fragmentary stories as examples of annihilatory thinking about language and identities from two modern partitions – the partition of India and of the Balkans — whose horrors erase the line separating self-regard and cynicism, fanatic convictions and cruelty. The first, by the Urdu writer Manto, is from a collage of laments, entitled “Dekh Kabira Roya,” in which the great saint-poet Kabir, watches with sorrow the ruins of language, religion and society left behind by the partition of India in 1947. As Kabir wanders through modern Lahore, he weeps over the vandalism of language and the corruption of the religious identities.[8] In the visionary poems of the historical Kabir, Sanskrit and the vernacular sing together; the words of city streets and village fields, the rhythms of ordinary speech and wandering bards weave songs that are ecstatic dialogues with other men and God. In Manto’s fictional text, however, the people Kabir meets in Lahore, after the genocidal days of the partition, obscure the distinction between words and daggers, and confuse their passion for slogans with thought.

One day, Kabir, who is a Muslim, sees a street-vendor tearing pages from a book by the Hindu Bhakti poet, Surdas, to make paper bags. Tears fill his eyes. When the vendor asks him why he is crying, he says, “Poems by Bhagat Surdas are printed on these pages… Don’t insult them by making paper bags out of them.” The vendor laughs, and says: “A man who is named ‘Soordas’ can never be a bhagat (saint).” The vendor’s taunt is made up of a foul pun on the word ‘sur/soor‘, which in Sanskrit (‘sur‘) means ‘melody’ and ‘harmony’ as well as ‘angel’ and ‘god’, but when slurred over (‘soor‘) is the word for ‘pig’ in Punjabi.[9] And since the word ‘das‘ can mean both ‘slave’ and ‘disciple’, the vendor’s becomes a part of the virulent religiosity that lay behind partition politics. Self-justificatory religious identity and linguistic contempt reduce a common world into a barbarous world; both push us towards annihilation and make mercy impossible.

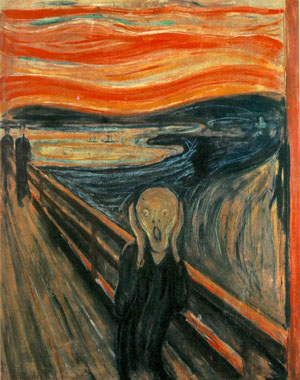

The second story is from the Albanian novel, Three Elegies for Kosovo (1998) by Ismail Kadare[10] about a land where the nightmares of identity are so “ancient and cold as stone” (p. 66) as to have become inerasable part of the memories and songs the traditional bards of the Serb and the Albanians sing. Even when there is peace between the Serbs and the Albanians for a period of time, or the Turks are attacking both, their minstrels cannot help but sing: “Rise, O Serbs, the Albanians are seizing Kosovo! A black fog has descended – Albanians, to arms, Kosovo is falling to the pernicious Serb!” (pp. 67-68). In the midst of their many wars, a Turkish subaltern happens to fall in with Balkan Christians. The Turk continues to pray in the Moslem way, but is so curious about both Christianity and Judaism that he learns to make the sign of the cross correctly and seeks to know more about the Jews. It is not surprising that he becomes a heretic for all the three religions; an impossible invention of demons who must be exterminated. As he is burnt at the stake, he screams in his own ‘strange’ language. The crowd is at first convinced that he has reverted to his ancestral faith and asked for mercy from “Allah”. The inquisitor is sure that the burning man, in league with the devil, is chanting “abracadabra” like a sorcerer. One of the Bosnians thinks that the Turk is screaming the word “ablla“, which means ‘mother’ in Turkish. But word the Turk had uttered was the world-despairing, faith-negating, terrifying curse, the first Latin word he had learnt upon entering the Christian dominated Balkans: “NON,” — “No, nothing beyond the fire and the burning body, the vision of moral and spiritual void.” In the novel, it is the deliberate refusal of human beings to recognize that other faces, other languages, other religions are nothing more than reflections of the same face, language, religion and Self,[11] gave rise to that merciless scream, uttered centuries ago by a poor helpless man seeking only an affirmative faith with others from a region known as the ‘plain of crows’ (Kosovo) — a carrion region of endless wars — can still be heard in the 1895 woodcut of Edvard Munch called “The Scream“, the 1953 painting by Francis Bacon called “The Screaming Pope“, the 1972 photograph of the naked Vietnamese girl screaming down the road as her skin and bones are burnt by napalm, 9-11-2001 photograph called “The Falling Man” and the 2003 acrylic work by Tyeb Mehta called “The Falling Figure With Bird“.

Even as we are witness to the fact we have often allowed reason to sleep, languages to become a curse and religious or ethnic identities to drift into a dangerous delirium, we must try to find a life-affirming, community-making future through languages and identities. Instead of being merely the fated fools of time we have to become rational participants in and makers of the karuna of time (time’s compassionate and merciful artificers). In order to suggest a way of finding a way into our own peace-sustaining linguistic traditions, identity formations and a culture of attentive regard for the other even in times of carnage, I would like to use the following anecdote. Anecdotes may be trivial, but as Carlos Ginzburg has shown quite wonderfully, they can illuminate how a society can articulate an idea of its own moral worth.

I want to first record the following conversation the late philosopher Ramchandra (Ramu) Gandhi once narrated to me after the fall of the Babari Masjid. One evening, as the sun was setting over the Ganges flowing through Benaras (it may have been one morning as the sun was rising over the Ganges if one were trying to reaffirm life’s journey into another glad day, instead of seeking consolation at the end of another day of erosion of our hopes, he found himself sitting by chance (for chance as we all know greets us often with choices we should make, adventures we should undertake, or insights we desperately need), next to an old Muslim gentleman on the bank of the Ganges. As they both washed their feet in the river’s water, Ramu asked the old gentleman in Hindi (it is important for me to record it first in the language in which the anecdote was narrated before working on the difficulties of translating it):

Ramu: Bade Mian, aap yahin kab se hain?

The Old Muslim Gentleman: “Hum to yahin shuru se hain.”

I asked Ramu if I could translate it and use it. He thought about it for a while and said, because his query and the response to it were rich with ambiguities, he’d think about it and get back to me. He never did.

I do not intend to unravel here the difficulties of translation since that is not my subject. Instead, I want to explore the sentiments of the communitas that once was an aspect of India’s religious traditions and whose presence can still be felt in the question and the answer. Keeping in mind that ‘Bade Mian‘ is almost always a term of respect for an elder Muslim gentleman, Ramu’s question, asked with full awareness of the complexities involved, could be translated as follows: “Bade Mian, since when have you been here?” In Hindi the question could well imply any of the following ideas: “Since when have you been sitting here beside the Ganges watching the sunrise/sunset?” Or, “Since when have you been living here in this city of Benaras regarded as holy by the Hindus?” Or, “For how many generations have you, your family and your community been abiding here in this city?” Ramu’s question can be understood either as an innocuous inquiry about the man’s personal history or as an attempt to establish his religious identity and its political and emotional articulations.

The old Muslim gentleman’s answer is equal to Ramu’s subtlety. In its simplest form it can be translated as: “I have been here since the beginning or forever.” This is in itself quite wonderful for it asserts joyously that he has been at the banks of the river watching sunrises and sunsets ever since he can remember. But the pronoun ‘hum‘ can also be translated to mean: “You and I have been here from the beginning or forever,” thereby, and with courtesy, agreeing readily to dissolve his own exclusive self-identity as well as his Muslim selfhood so as to include his Hindu neighbour by the bank of the Ganges in his vigil of / vigilance over the river sacred to the Hindus and the cycle of days common to both the religious communities.

But, the pronoun ‘hum‘ can be translated more inclusively. “We (Muslims) or we (Muslims and Hindus together) have been here from the beginning/forever.” This translation acquires greater significance if we remember that it is being made not only after the Partition of 1947 and its great slaughter, but also in the midst of long history of continuous communal riots across the subcontinent as a consequence of the Partition (I am conscious of the possible provocation in the statement). What it, thus, contains is an act of rememorialisation of a syncretic tradition which all the religions of India have contributed to and sustained. By making the idea of a composite culture as the “moral truth”[12] of the of the Indian subcontinent, the old gentleman’s answer also makes important historical comments which it is important for us in this context to spell out. Unlike much of the fictional literature about India’s Partition, he refuses to locate the idea of a desired and tolerant community in the past. In notes of quiet, unselfconscious confidence, he not only evades nostalgia, with all its incurable sickness for a place called ‘home in some unavailable time, but also assumes that his ‘home’ is where he is at the present moment. He also makes us understand that, not only was the Partition an absurdity and an aberration, but the continuing conflagrations in our city streets need not yet dishearten us. Stupidity can be overcome, he seems to suggest; injury can be healed; but what can not be forgiven is the despair which makes us believe that it is impossible for us, ever again, to make a compassionate and cosmopolitan civilization. The logic of our surrender of hope is that we will retreat into our exclusive identity-fortresses and demand for our own survival either the death of others or the sacrifice of our own selves. The politics of identity, which is always paranoic, can only lead us to terrorist violence and make the earth into a charnel house.

I want to use the conversation, between a Muslim and Hindu philosopher who saw himself as a disciple of Advaitan saints, to move even further away from the estrangements and idolatries, exclusions and deportations which are inherent to all politics of partitions. If one uses the site of the dialogue, its tone and its possible translations one cannot help but dissolve the absolute immanence of the individual and the religious groups to which each belongs. It is emancipatory to think of Ramu and the old man saying to each other — you and I, separately and together, sitting under that sheltering sky on the bank of this river, sacred to both of us, with our feet trailing in its waters swiftly flowing towards the sea, watching the sun rise or set, are, and have been, at home, here, from the very beginning of time; both, you and I, a Muslim and a Hindu, can claim to be the rightful moral and political inheritors of this city and keepers of this river.

My reading of the conversation moves with slow deliberation between a singular language with its particular nuances and its possible translations searching for significations relevant to this meditation. The scene that I am trying to reconstruct is one where there is ease and gracefulness which persist and abide even in our historical moment of terror, corruption and endless justifications for murder. It is sometimes consoling to remember that the political, however battered it be at present by the brutes, can yet be elegant, and that the “city of the mind” can still put up a resistance to colonization by the irrational. As the poet Paul Celan, who survived one of the many holocausts of our generation, says, it may yet be possible to be in places where one can survive so as to:

“live the lives, live them all

tell the one dream from the other,

look, I rise, look, I fall,

am an other, am no other.”

Apart from suggesting that we do not have to “thrive on bones (for) without them there’d be no stories,” as a contemporary novelist of despair says,[13] I want to use the conversation to sound a note of caution and conscience.[14] Apart from assuming that any human speech makes demands upon our imaginative sympathy, I want to argue that a monolingual and a vernacular self is as capable of making a tolerant community with others as the self which carries a multi-lingual passport giving access to all the cosmopolitan centers. If the eagle knows the canopy of the covering sky and can see the earth below, the mole knows the earth and can see the sky above. Neither has an ethical superiority, and by assuming one we are in danger of partitions which can be as lethal for human rights as they always are for political rights. A multi-lingual self in the present global economy may make a new techno-economic society operational, but it does not necessarily make it into an operationally better community. In the Indian context, Ravana, the demon-king with ten heads, is multilingual.

My mode of reading and translating the conversation acknowledges the difficulty of knowing the other, but refuses to accept the complacent assumption that the other is always opaque and hence not worth the effort. Human beings are not transparent to each other. Why should they be? They call upon our reason to gather many of the implications of their words and, at the same time, out of respect, let some lie hidden in the recesses of their subjectivities; only dead things can be anatomized and the details of their classifications translated in their entirety. It is ethically proper to leave some aspect of the human-self untranslated and untranslatable. If we accept this, then we can, not only tolerate differences but also respect them, encourage them, and indeed, acknowledge them as essential for our selfhood. We can even make a more radical move and, as the Dalai Lama says often, joyfully assert that many gods together can look after an infinite variety of our needs – even of those of us who do not believe in their existence. All paradises, after all, must have a place even for those who know that paradises are an illusion. I suspect that only such an understanding can turn us away from becoming the demons of sectarian rage and become, instead, participants in a human conversation were all conclusions are always provisional and every proposition can be questioned or contradicted.

Further, since the conversation is carried out in an ordinary language spoken by ordinary human beings, I want to use it to reject the assertion that some languages are doomed to wander in the dark alleys of exile unless they become the raiders of the ark, while others possess the clear light of day. There are no sacred languages and, hence, there is no hierarchy of languages. Languages are not at war with each other; nor are there some languages which are better suited to help us discover a way of ‘being’ in the world. It may be altogether useful for us to abandon all arrogant regard for our own ‘mother tongue,’ along with pathologically possessive love for our ‘native soil’. For, unfortunately, both make us assert, with a great amount of sentimental self-regard that our particular human experiences can never be translated and hence understood in any other language – for ‘mother-land’ and ‘mother-tongue’ are two metaphors which are inextricable from the politics of partitions, exile, pain and blood. We need, instead to assert that the language we use for all our purposes is the language ‘of our own learning, our own finding’. The task of any critical education is to facilitate that discovery and that knowledge. It may, therefore, be useful to erase idea of the ‘native-soil’ and ‘native-tongue’ (as well as U. R. Ananthamurthy’s charming, but sentimental and false distinction between the language of the inner-courtyard, where the women live in community and the remote upper-room, where the father lives in isolation)[15] and suggest another more inclusionary metaphor under which all of us together can find a shelter, and say that all languages have there roots in the sky and their trailing branches and leaves, different from each other in every respect, reach down to every soul with equal generosity. This metaphorical change may enable us to imagine that each language, moved by the same breeze, borrows from, distorts, transforms or slides into any other language with ease, and that every society, through its interaction with others at its borders, is continuously engaged in the transformative process of world-making and knowledge-making. One can, for example, point to the manner in which Hindi/Urdu/Punjabi/English have existed side by side over a long period and have utterly changed, through their co-mingling, the world-views reflected in each, and opened up spaces of knowledge for each which they may not have found in their isolation. If I am right then all partitions can only transform language, identity and religion into sites of bitter wreckage.

Finally, I want, as piece of visionary archaeology, to imagine that Raphael’s magnificent painting, The School of Athens(1510-1516), commissioned by Pope Julius II for a wall in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, has come to life a few decades after the death of the great Argentinean writer of Spanish stories, Jorge Luis Borges. Borges walks into school where Averroes, the famed Arabic scholar and the translator of The Poetics, is asking Socrates, Plato and Aristotle what the word ‘tragedy’ may mean. Arabic, he tells the Greeks, does not seem to have the concept. Borges, who has been reading Averroes, and knows that words exist in labyrinths of dictionaries and that experiences repeat themselves endlessly in corridors of mirrors, walks in and, overhearing the conversation, asks in Spanish if tragedy is possible where stories of deaths and murders endlessly repeat themselves from generation to generation. Can such nightmares of historical repetition be dignified by the term ‘tragic’? Neither Averroes nor the Greek philosophers understand him. I imagine that somewhere, leaning against one of the majestic pillars of the School, Mirza Ghalib, one of the finest Indian poets of the 19th century, and victim of colonial contempt by the British, welcomes Borges and, turning to the assembled scholars, asks, not in Urdu, but in Persian in the hope that someone there would translate his question (and surprisingly finds one in Shamsur Rahaman Faruqui):

If there is a knower of tongues here, fetch him;

There’s a stranger in the city

And he has many things to say.[16]

I hope that such a school of Athens, where courteous discourse is possible will once again be established.

Notes:

[1] The Power and the Glory (1940; rpt.: London: Vintage, 2001), p. 188.

[2] Phrase is used by Marilyn Vogler Urion in, “…Thighs,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 21, no. 3 (2002), p. 154.

[3] Martin Buber says “Everyone that lives in the land of Israelis like the man that has a god and everyone that lives abroad is like a man that has no god.” Quoted by W.T.J. Mitchell, “Holy Landscape: Israel, Palestine, and the American Wilderness,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 26, no. 2 (2000), p. 193. Mitchell’s angry comment on this sentiment of ‘holy land’ is worth noticing: “…every holy landscape seems to be shadowed by evil…The holy place is a paradise from which we have been expelled, a sacred soil that has been defiled, a promise yet to be fulfilled, a blessed site that is under a curse.” Such a site demands the sacrifice, often of others, performed with “ferocity and religious fervour” (p. 194).

Mitchell also quotes Emamanuel Levinas who says, contrary to Buber, “A person is more holy than a land, even a holy land, since faced with an affront made to a person, this holy land appears in its nakedness to be but stone and wood” (p. 193).

[4] As he meditates upon the secular killers of Catholic clergy, the ‘whiskey priest’, who makes no claim to ethical superiority in Graham Greene’s novel, The Power and the Glory, says, “it is odd – this fury to debase, because, of course, you could never debase enough.” (1940; rpt. London: Vintage, 2001), p. 102.

[5] In The Power and the Glory, the priest speaking with utter humility, but without sectarian rage, speaks about, “…what god intended for men – the enormous privilege of life – this life” (p. 60).

[6] Michel de Montaign is right when he writes: “…for it is not said that the essence of thinking has reference to man alone…” quoted by Helene Cixous.

[7] This is with a gesture towards Wallace Stevens’s war poem, “Letters d’un Soldat.”

[8] In his fine book about what makes a ‘home’, Gaston Bachalard says that in exile the space of intimacy and well-being is “expunged from the present” and is, hence, “alien to all the promises of the future.” Poetics of Space, trans. by Maria Jolas (New York: Orion Press, 1964), p. 10.

[9] “Dekh Kabira Roya,” Dastavez, vol. 4, ed. by Balraj Menara and Sarad Dutt (New Delhi: Rajkamal Prakasham, 1993), p. 255. The translations included in the text are by me.

[10] Three Elegies for Kosovo, trans. By Peter Constantine (London: Harvell, 2000).

[11] The Shavetashvatara Upanishad says: “The world is full of your faces…” Quoted by Ramchandra Gandhi in Muniya’s Light (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2003), p. 107.

[12] Jean-Luc Nancy in The Inoperable Community, translated by Peter Connor (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1991), rightly asserts that “A community is the presentation to its members of their moral truth.” There can never be, Nancy argues, an unmoral community. A society, however, can be an indifferent collection of people (p. 15).

[13] Margaret Atwood, The Blind Assassin (New York: Doubleday, 2000), p. 11.

[14] I have in mind here Rabelais’ Gargantua telling his son: “Knowledge without conscience is but the ruin of the soul.”

[15] For a fierce counter-proposition to the idea that women’s language is more finely tuned to the essential pulses of life and all the imaginative resources that lie in the myths and legends of a society, read what contemporary American feminist poets have to say in Alicia Ostriker’s, “The Thieves of Language: Women Poets and Revisionist Mythmaking,” Signs, vol. 8, no. 1 (1982), pp. 68-90.

[16] Translated by Shamsur Rahaman Faruqi in, “A Stranger in the City: The Poetics of Sabk-i-Hind,” Critical theory: Perspectives from Asia, ed. Naqui Husain Jafri (New Delhi: Jamia Millia Islamia and Creative Books, 2004), p. 180.