Freedom is a Slippery Fish (An Introduction to the Lead Feature): Trisha Gupta

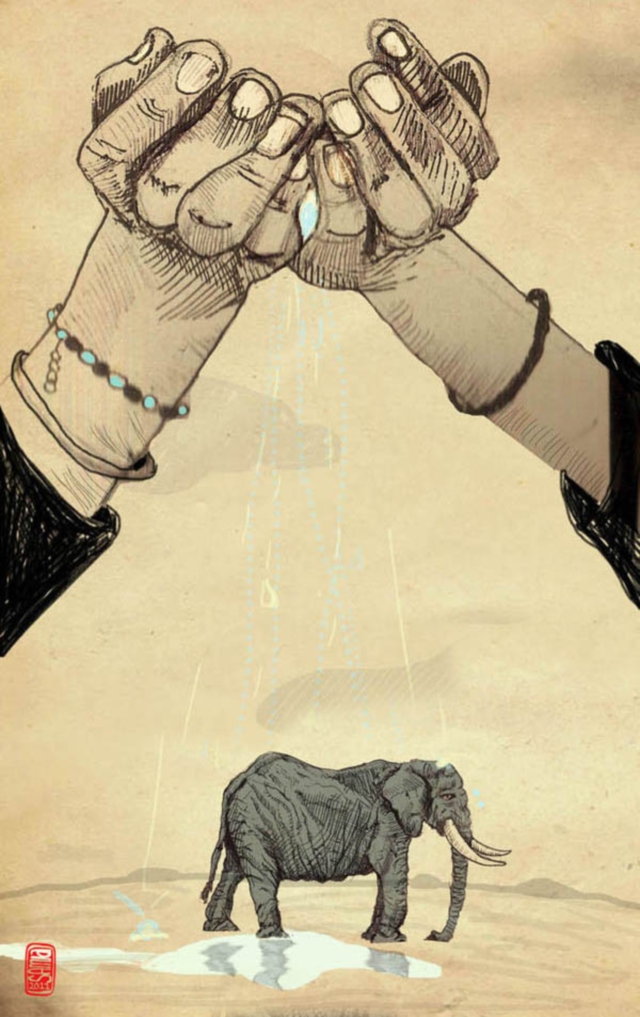

Art: Samia Singh

Freedom is one of those words. As the cornerstone of our conception of democracy and of modernity itself – or simply as the easiest answer to what so many of us think we aspire to in our political and personal lives – we ought to know exactly what we mean by it. But freedom is a slippery fish.

For one, it means different things to different people: a woman may feel that wearing a veil offers her freedom of movement, or is an act of cultural/religious freedom, rather than an expression of gendered oppression. For another, in an unequal society, freedom can often be the selective preserve of some – maintained at the cost of the labour of others.

In ancient Greece, for instance, freedom for a few was premised on the unfreedom of the many. The life of the polis – the active political life that was considered the highest form of being-in-the- world – was made possible by the fact that citizens had wives and slaves whose labour took care of their everyday needs. “In order to be free, man must have liberated himself from the necessities of life,” wrote Hannah Arendt.

And yet this liberation was not enough to enable freedom: freedom needed the company of others in the same state, and a common public space in which they could meet and act collectively. Freedom, in other words, was contained in the ability to act in the public sphere, in conjunction with others of one’s ilk. There are two things to note here: that freedom in the Greek sense involved being part of a collectivity, and that this collectivity could only include some people. (There is a straight line from the ancient Greeks to Jurgen Habermas’s notion of the public sphere, with the difference being that access is meant to be guaranteed to all citizens – at least in theory. Unfortunately, the suspension of social and economic hierarchies on which this ideal is based often remains illusory.)

Meanwhile, as Arendt points out, if the ancient Greeks took freedom to mean freedom for politics, the history of liberalism has construed freedom in exactly the opposite way – as freedom from politics. In this understanding, freedom is not defined by the ability to participate in the creation of a state but instead non-interference by the state, which would leave people free to conduct the business of the social and economic sphere. In other words, the market.

Whether life in the so-called free market is actually free, or whether it has us all in its illusory grip—such that our desires are contained and moulded to fit its pre-conceived ideas of fulfilment— is an important question, and a never-ending one. But perhaps freedom often emerges in the interstices between the big questions, its achievements wrested – as in Shahrukh Alam’s marvelously observed slice-of-life tale of the breaking and rebuilding of Dani Limda – through quiet, strategic negotiations more than declaratory announcements. The grand rhetoric of freedom can sometimes be, as Aruni Kashyap’s evocative poems show, a blustering cover-up for terror.

Arendt’s difference between freedom from and freedom for finds an echo in another trajectory of thinking about freedom – the idea of negative versus positive liberty, most commonly associated with the philosopher Isaiah Berlin. Negative liberty is the assertion of freedom from external restraint: the interference or direction of others. Positive liberty lays claim to freedom to realize one’s own self – the restraints being battled here are internal to oneself.

In some way or another, every conversation about individual freedom turns on either of these axes: to be free from the control of others, but also to be free from one’s own internal censor—or one’s internal hankerings. The battle with oneself is what animates Bengali writer Syed Mujtaba Ali’s relling of Rumi’s deceptively simple tale ‘Tota-kahini’. Presented here in a lucid translation by Ujjwal Gupta, ‘The Story of the Parrot’ is a little gem, marshalling the vast resonance of folk wisdom to the task of freeing oneself.

But is freeing oneself from worldly desire the only possible path to self-realization? Nikhil Govind’s fascinating meditation on the Rama story and the Buddha story contrasts two paths to freedom: freedom achieved in the world, and freedom achieved by rejecting it. These two classical narratives, both still so familiar to us, are ur-texts of freedom – ones that may actually have been in competition with each other in the Indo-Gangetic plain some centuries before the Common era. Both are narratives of princely exile, but with a crucial difference – the Buddha chooses his exile, Rama does not. “Rama rejects passively – he is doing it as a son for his father’s vow, and as king because the people must not doubt.” And yet, Govind writes, “The ethical argument of the narrative makes clear that duty (dharma) must coincide with freedom, and that this coincidence has nothing to do with what the people think”.

It is not quite clear, in other words, that Rama’s travails are caused only by ‘external’ fate. Is Rama, as the Valmiki Ramayana itself asks, “caught in the trap of his own righteousness”? The sense of being caught in a web of obligations – externalities that slowly begin to reveal themselves as patterns of our own making – is an undercurrent in Parvati Sharma’s ‘Rethinking Aurangzeb’. Excerpted from Sharma’s forthcoming novel, the piece is droll and elliptical in the telling. It creeps up on you slowly—and yet its quicksilver changes of mood can catch you unawares.

Sharma’s Koel is one of several characters here who make the discovery that what you most yearn for can sometimes crush you in its stifling embrace. There is Ashapurna Debi’s Bilu, whose childish insistence on wearing a sari sends her hurtling into an adult world whose pleasures and tribulations she is only half-prepared for. Bilu’s particular sartorial longing may seem to belong to 1958, but her anxious giggles – as she wonders how to fend off the unexpected effects of her newly acquired freedom – are soul-crushingly recognizable. Then there is Sabbah, the ever-mobile protagonist of Nisha Susan’s story, who finds out how easy it is to slide from feeling “ridiculously replete with the luxury of being a writer” to feeling increasingly hemmed in by the expectations attendant on writerliness in contemporary India: the agent, the twitter account, the literary festival. Being surrounded by her own kind swiftly comes to seem less liberating than she imagined it would: “How could she possibly waste her short life with self doubt? She only had to make sure that she was never again in a room with more than two writers.”

Other contributors are interested in the ways a space – or our imagining of it – can hold us in its grip, or hold out the possibility of escape. Smriti Ravindra’s haunting little piece evokes a space almost iconic, at least in this country, for its unfreedom: the girls’ hostel. But even as the young women of ‘Prayer Flags’ are surrounded by a wall of barbed wire; the ghosts of their thoughts are free to roam. In the atmospheric ‘Furlough’— translated by Daisy Rockwell from Upendranath Ashk’s Hindi original, which later became a part of Ashk’s novel cycle Girti Deewarein (Falling Walls)— a young man dreams of Shimla as a longed-for respite from the everyday hurly-burly of life in the city. And as his slowly-chugging train leaves the heat and dust of 1930s Lahore behind for the cooler air of the hills, the compartment becomes the site of unexpected forms of kinship. Another evocation of space is Umair Muhajir’s ‘Freedom’: a translucent memoir of growing up in Dubai in the 1980s, and of the way that Hindi cinema worked for him as a kind of imaginary homeland—a country free of borders, in which all you needed to become a citizen was to proclaim yourself one.

The ultimate form of imagined community, of course, is the virtual universe. Sumana Roy’s piece takes on the formidable task of thinking about our freedoms as reconfigured in the digital age – but thankfully refuses the ponderous conclusion in favour of the sharp, knowing aphorism. “On facebook, we are all freedom fighters,” she begins, taking us on a journey through facebook that is slyly ironic, thoroughly eccentric and continually revealing. There are the many who use facebook to create new, fictive identities or hide existing ones. There is the hacker Bhai-Rus, who believes the logical conclusion to freedom of information is a world shorn of privacy (while of course retaining anonymity for himself). There are bras tossed into the sky, flags of freedom.

The enforced unfreedom of female attire is the subject of a characteristically sardonic piece of writing – a poem – from Ambarish Satwik, mapping an ironic history of the constriction of women’s bodies by clothes designed to signal their ‘freedom’ from labour. “And in these matters the quantifier/ Of leisure, the favored artifice,/Was the womanliness/ Of the woman’s apparel – the degree/ In which it argued/ Exemption from labor.”

In a very different attack on aesthetics, Savita Singh gives us a feminist deconstruction of ‘Tootee Hui Bikhri Hui’, perhaps the most well-known poem written by the legendary Shamsher Bahadur Singh, a surrealist-cum-leftist poet with the reputation of being a kind of high priest of beauty. In unearthing the patriarchal underpinnings of a text often hailed as one of the greatest aesthetic achievements of modern Hindi poetry, Singh’s reading might be said to be speaking Truth to Beauty (with apologies to Foucault).

Manisha Pandey’s piece ‘Ek Akath Shabd ki Jeevani’ (The Biography of an Unspeakable Word) is another forceful act of truth-telling. A personal response to the recent debate provoked by the Delhi gang-rape case, her piece is a searing indictment of a society in which the spectre of rape not only keeps women from exercising their freedoms—the freedom to roam the streets of villages, towns and cities that are as much ours as those of men, the freedom to own our bodies, the freedom even to experience desire—but couches our very imprisonment as freedom, from “that unspeakable thing”.

The four remarkable Tamil women poets presented here – Malathi Maithri, Salma, Kutti Revathi and Sukirtharani – are united by their fierce commitment to speaking the unspeakable: writing in specific and personal terms about their sexuality, their bodies, their inner lives. As translator Lakshmi Holmström points out in her introduction to the forthcoming anthology of their work, the traditional values prescribed for the ‘good’ Tamil woman were accham, madam and naanam (fearfulness, propriety and modesty). Instead, these poets have chosen fearlessness, outspokenness, and a ceaseless questioning of prescribed rules—earning themselves vilification from the Tamil patriarchal establishment, and an uneasy fame.

And yet, it is not entirely clear that the paths to freedom must involve a wholesale rejection of ‘tradition’. All these four poets have a strong sense of working with (if not always staying within) a rich and various cultural inheritance: Maithri, Revathi and Sukirtharani all draw on the erotic landscape imagery of ancient Tamil Sangam poetry; Revathi’s understanding of the body is influenced deeply by her lifelong interest in Siddha medicine; Sukirtharani’s work embraces a Dalit world and history, turning its humiliations into pride. Another woman’s freeing engagement with a great tradition is documented in Mrityunjay’s translated excerpt from classical vocalist Gangubai Hangal’s autobiography. One gets the feeling that she lived in an alternate universe, one in which the demands of domesticity could be suspended in the unhampered pursuit of music. Her husband, even on his deathbed, insists that Gangubai must leave for Delhi for a performance.

The protagonist of Ratika Kapur’s ‘A Good Woman’ has seemingly more ordinary worries. Mrs. Renuka Sharma is the average middle class Indian woman we all know—a woman who has learned to live with her external constraints and at least partially internalised them, a woman who knows she cannot throw caution to the winds: “I am not that kind of woman”. And yet, even as she says this, Mrs. Renuka Sharma is taking her own baby steps towards being another kind of woman. She is taking them unaided, at her own pace. She has not yet become, to use Umair Muhajir’s marvelous phrase, the Nirupa Roy of her own life: stuck in the same part, condemned to look forever backward, with no expectation of any redemption but fate. Perhaps, in the end, that is what freedom really consists of—the ability to imagine oneself in a new part. Or imagine one’s part in a new whole.

Have not read the whole issue yet. your editorial provides insightful introduction to the issues within the issue, contained in this issue.

The last para is particularly apt, the Nirupa Roy bit of Umair Muhajir is simply brilliant!

“The ability………in a new whole”.

a beautiful summing up