The Empty Space: Geetanjali Shree

Perhaps it was then, when the bomb burst. The bomb burst and we scattered. The moment was frozen forever and we, fixed eternally in that moment. Ash flying, fires raging, scraps of flesh airborne. Fans, gulabjamuns, pav bhajis, idli vadas all flung about as if an argument were taking place in the cosmos. Modern day cafes – that’s how they are. Idli vadas not restricted to the south nor pav bhaji to the west. This here, that there, each of them can be found everywhere. Ever had fans in Paris before? And bombs? That’s the biggest joke of all. They can turn up anywhere, at any time.

But it was a first, for that café. Known till then as a safe area café. It was in the university. Boys and girls, young men and women holding admission forms, new meetings; which part of the earth are you from? Admission wasn’t certain but it certainly was an age of hope. The university was to open for the entrance test and there’d been a stream of students since morning. Getting the jitters? Well naturally. Take a break, go eat something; then get a move on. We shall overcome one day. There was no room in the café, things one on top of the other, pushing, shoving.

There was just one empty space, the size of a three year old child; I was that child.

I remember all of this. Believe me if you will. Feel free to trash it if you don’t. The way I remember it, I was in the sack that held the bomb. The bomb burst, scattering shrapnel just where there was a space lying empty, the right size for a child like me. It looked like it was meant for me; I fitted it perfectly. That’s what saved me from burning. There I lay like a god in the midst of screams from around the fire. Or maybe like a demon. I was alive, at any rate. Should I have smiled then? Or cried? I ought to have done nothing perhaps. So I lay there, just lay there. The fire kept burning and I was freed of old memories as new visions seeped into me. Then things took their course; the distinction between memory and fiction faded and my entry into this age became easy. The age itself became ordinary and what of the bomb? All traces of it have vanished and the mundane round of things continues.

The scene looked something like this. The café sizzled in the fire as I leapt out of the bomb. There were people running everywhere, spurting fountains of blood, looking like martyrs at the gallows. Those who could run away did. The ones left behind spewed fountains that became fire. And they turned into charcoal; waiters and children and chairs and plates.

He was there too.

Eighteen years old. His blown up bits returned home hammered into a coffin provided by the government. The shreds of his body had spread over the length and the breadth of the café, to be collected and brought home in the government coffin. Like others who’d stood around eating samosas etc. before the exam, samosas that turned to ash before they could be eaten.

Those shreds. The papers kept giving accounts, year after year. The charcoal crumbles into the news even today. Then there was my version, experienced at first hand, seen with my own eyes. As I lay there in the midst of the fire, demon, god, an empty space. Safe amongst the flying scraps of flesh.

When the café had been burnt to cinders and sirens announced the arrival of the police, they found the lump of a three year old child, red and crawling with ants, lying there not wailing or crying yet alive, being eating away by ants or perhaps being saved by them.

[…]

Some pieces, the rest of it, ash.

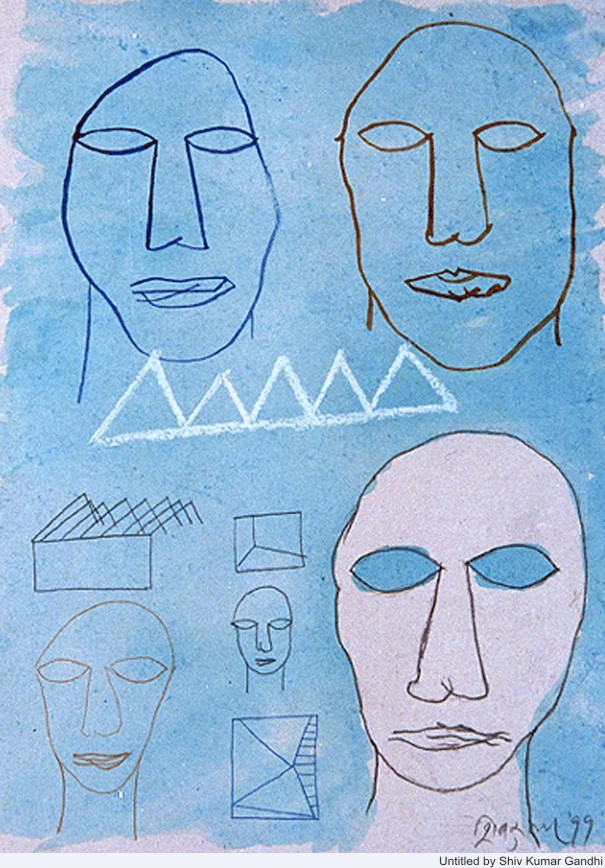

The fans of the café melted soft and supple like dancers striking poses. Rows of dishes, dust-cloths, to say nothing of bottles, all were dark exhibits on display. The entire café could have been the black dream of an artist. Broken pieces, like abstract art. They could have been chairs or tables, idlis or sambhar, gulabjamuns or pav bhaji, burnt black, shattered and unrecognizable. Maybe they were people, boys and girls, caught just before they entered the university building. The pieces that might have added up to nineteen people had the destroyer known how to mend, to create afresh, had he been Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh all rolled into one.

There were nineteen people to be identified; fragments to be made sense of. In order to do that, they’d first have to be laid out in pieces, and here the attempt was to unify the pieces into a whole.

And there was I, a piece that was whole, being eaten away by ants or maybe saved by them.

[…]

Nineteen flesh and blood people whose remains now lay scattered all over.

There was one more, in another place.

The process of identifying them began. There was a shirt collar. A half burnt ten rupee note, a map of a foreign country, an admission form. A singed reference letter with yellow brown writing that might have been in a museum. Who could find something, if indeed there was anything to find in this heap of cinders?

Detectives set forth into the city. All the missing from the city must be right here, in these ashes. His family didn’t think so. He’d disappeared before, it was a habit. He wasn’t the only one who did this. Other residents and visitors disappeared and appeared at will.

This didn’t dissuade the detectives. One, two, three, the process of identification went on. By and by, sixteen heaps of ash had been definitely identified: name, father’s name, father’s father’s name. That left seventeen, eighteen and nineteen. Two more were guessed out of the mound of ash and made into human beings. The nineteenth remained.

One left to be identified. That was him.

I was another.

He and I!

Who are they? Who?

There was a picture of him in the papers. So was mine. No phone number for me. He had a number and parents’ name.

“That’s not him,” said the father. “It can’t be him. How could it be when he left just five days ago? He wanted very much to go. That’s all. That’s all I know.”

There was nothing they could do but make phone calls. The father would call; the mother sat by his side. The father called and mother would sit, eyes closed. Father called and mother stared, eyes open wide. Phone calls to the university, to the police, to the newspapers, then to the community council, the supreme council; they called all those worth contacting.

What did you find out? Find out anything? Just that a bomb exploded. In the university café. Never happened there before. The lists were incomplete, those of the missing as well as of the ones who remained.

Don’t worry, said friends and acquaintances. In that hour when the earth got vertigo.

“Don’t worry”, the father repeated to the mother. “Wasn’t it just yesterday that he called to say he’d be going to see one of those seven wonders so close from there? That’s where he must have gone, what else?”

The identification continued. The town was densely populated and things were made worse today by the influx of outsiders. Admit cards, exams, new students and their parents with dreams in their eyes, a surging tide of people; anything could happen and in fact did. A bomb could have gone off and did. People could have died and did. But they could have been saved, too.

“They still haven’t finished the list of those who are hurt.” The father snapped at the mother. “Don’t keep calling and holding up their work!” That, when it was the father who held the phone while mother sat with mouth tightly shut.

Well, let them get on with it, find out which is a heart and which a finger. Was this a pakora or someone’s liver?

Were they waiting for the list of those missing or for the admission list? One seemed like the other. Another name finally… Where did my child find a place? On the list of the saved or the doomed?

There were more and more names, one after the other. His seemed to be the only one that wasn’t there.

Could it be pure coincidence? That he and I were the only two left to be identified? No one had a clue about me, either. He and I; there we were with our separate selves, and no information about either. Just the two of us.

Did the confusion between us become permanent? Between him and me? There was one dead left to be recognized and one alive. Who was dead and who alive? Jokes apart, did they find out?

It was all a mix up. One was in pieces, the other an unclaimed piece. I was choking in the smoke and there he lay battered, with the smoke around him. He was dead and I alive, both without an address. Or was it that he was alive and I dead, both unknown?

We were waiting for our names to appear on the list, to be recognized from our photos in the papers and be claimed, taken away.

But no one called for us. No wonder of the world.

Just the father was called, to come and sign on the papers. It was the father’s signature that was needed. No need for the mother to come.

[…]

The mother’s always needed, though. The father holds the ashes in his clenched fist and the mother makes sense of it all. Is that the button she sewed on to his shirt? It’s the mother who can tell, not the father. She is the one who remembers how long the string was that she wound round a pencil to draw through his pajamas. She knows the pocket too, in which she’d put the good luck toffee that would have, had he put it in his mouth, defused the bomb before it went off.

It wasn’t the police; the mothers had taken it upon themselves. All of them turned up; the mothers who’d sent their children for a good education, so they might help lessen the woes of the world. They had arrived to identify and separate idlis and gulabjamuns from heart, kidney and liver. In the uniform spread of ash, which was the idli, soaked in curd and cooked in steam, and which the child’s guts created out of her own being?

Mothers started out in cars and buses. Factories and shops burnt to the ground, the black carcasses of buses, all were testimony to the new look of the town, right up to the café.

The women found the café completely burnt. For the moment there was a pause in the wailing. The sky was blue, the day bright, as though the women had not descended from the bus but from above, like beams of light.

If life is a story then each image is a sign, each small thing a signal.

After the blast, the café had now been declared to be in a sensitive area. Rioters fell upon the city. It became dangerous to come to the café.

The women surrounded the café like terrorists. The police force that had come for their security backed off. The women had barely entered the café when clouds came up in the sky. And a minute later they burst into rain.

Everything seemed to be a sign coming together to create a saga!

No one goes to the café. The dark holds secrets glowing then dying, ghosts searching. There was clean, clear, dry ash in the café. Just ash smells, the whole scene ash, an ashen silence. The floor was ash, the air, the roof, ghosts of ash. There a button that she had stitched, a pajama string she had put in place.

The mothers’ footsteps fell tender just above the burnt ground. Distracted glances spread across the café.

The mothers did not place their feet on the ground, for who knew where… on whom…? They began to float gently. They opened the burnt iron cupboards one by one and the emanating clouds of ghostly ash floated with them. Ash from the ground rose and kissed their feet. Clouds of ash filled the devastated café and the mothers waved around within the cloud like candles, for their child could be somewhere here… or there…

The mother was floating like this when a tenderness sized space was below her feet, just big enough for a child of three to fit into.

Ash didn’t float in that space and it was there that the mother placed her feet.

(Translated from Hindi by Sara Rai)

a very fine prose and emotion on bomb.