When They ‘Tamed’ the Kosi: Deepika Arwind

IN PATNA, AND SOON OUT OF IT…

We arrive in Patna by the afternoon of March 8. The only news streaming out of the television is of the Women’s Reservation Bill. Lalu Prasad Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav are protesting the bill vociferously somewhere in this city, threatening to pull out of the UPA coalition if the bill is not put up for discussion. Meanwhile the Nitish Kumar-led Janata Dal (United) has favored the bill. Television hosts and anchors appreciate him for being ‘progressive’, all amidst talk of his political motivations.

Even though this bill is deemed momentous, the television is turned off for now, and we get ready for the week ahead of us.

We will travel to Saharsa District in North Bihar, often in the news for being affected by the yearly floods in the State. Saharsa is one of 11 districts in North Bihar, notorious for being ‘ravaged by the Kosi’, also referred to as ‘the sorrow of Bihar’. Many have heard of the Kosi’s wrath, but few know that the Bihar’s sorrow is swamped with complexity: it is a river tampered with, ‘tamed’ by embankments for over 60 years now, often lashing out and submerging villages instantly, only leaving fine white silt as a remnant of disaster.

The Kosi is one of Bihar’s most effervescent rivers, and starts its journey at a height of 7,000 meters in the Himalayas. But it is most fascinating because it has changed its course by over 160 kilometers between 1737 and 1948 from Sauradhar to Lajunia, due to the high deposits of silt it brings from its upper reaches. In its meandering, the Kosi has also abandoned many of the channels it used to once flow through.

After the Bihar floods of 1953, Jawaharlal Nehru asked for an aerial survey of North Bihar to be conducted and issued orders for embankments to be built from Bhardah to Bhanthi (measuring 121 kilometers), and from Bhimnagar to Bangaon on the eastern side (99 kilometers). The embankments are built on either side of the river, anywhere between 10 and 16 kilometers away from the banks. A barrage of 1,150 meters, five kilometers north of Hanumanth Nagar in Nepal was also proposed. The whole project, including an eastern canal, was estimated at Rs. 37.31 crores.

Inside these embankments lie close to 380 villages, and close to 14 lakh people.

The many stories that the Kosi holds around its embankments will only unfold as we get on the road, first following its course and then crossing over it, to reach Saharsa town in Saharsa district. We are a group of women journalists and writers, accompanied by those who have studied and surveyed the Kosi’s fatal embankments and the resultant floods for long. Leading the group through territories he knows well is Dinesh Kumar Mishra, an engineer and the convener of ‘Badh Mukti Abhiyan’, who has, for three decades now, advocated that the embankments along the Kosi spell disaster. The others include activists, researchers, and a few people from local collectives and NGOs, who have been joined by the cause of the Kosi for years.

As we drive out of Patna, it almost seems like the optimism of the city is palpable. Our driver, Binod Kumar Pandit, tells us how much has changed in the city since Nitish Kumar became Chief Minister. True to his name, Pandit has an air of learnedness as he points to the different things that have transformed, or are in the process of being transformed. The roads, for one, he says, have been improved drastically. Many over-bridges and flyovers have been built. The airport and the railway stations have been given a facelift, parks and public utilities have become more useable, he says. Back when Lalu Prasad Yadav was the Chief Minister, “nothing functioned smoothly, crime rates were high and hooliganism was rampant. A group of people sitting in a car, just like us, could be stopped and harassed for no reason,” he says.

And even as we are surrounded by optimism and the many wonderful stories of development here in Patna, the floods of August 2008 when the Kosi breached its embankment (a sign of ‘development’ and protection) – for the ninth time – at Kusaha (in Nepal) cannot be undone. In Bihar, as in the rest of the country, there is no single story of ‘development’. It takes us only a few hours of leaving Patna to realize that.

On the way to Saharsa District we see acres of Bihar’s unspectacular-spectacular topography of flood plains: Unspectacular because it is flat, and frustratingly so, for miles on end, stretching out into the horizon in the same way. And spectacular because it is just as unapologetic in its flatness, and lush too, even as summer begins its ascent. On the sides of the road, the houses are built so they can be dismantled easily during a flood. The flood, the ‘Badh’, is a part of their daily vocabulary, and negotiating it, part of their routine.

We stop at Khagaria town in Khagaria District on our way. Khagaria serves as a basin for seven of Bihar’s rivers: the Kosi, the Ganga, the Budhi Gandak, the Bagmati, the Kamla Balan, the Kali Kosi and the Kareh. We meet a group of journalists from Hindi dailies including Sanjay, the Khagaria bureau chief of Prabhat Khabar, who tells us how they report during the floods: using a boat, of course. The boat, he says, has also become the most common form of dowry. Meanwhile, in Khagaria, a project to encircle the entire town with embankments of 12-15 feet is underway.

‘THE SORROW OF BIHAR’

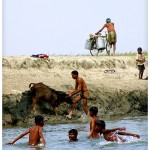

Almost half way to Saharsa we pull up on a bridge, where we finally meet the Kosi in its full form. All we have talked about up until now has been this ubiquitous river, and to stand at sundown above its calm waters is somewhat of a contradiction. How can something so serene be so temperamental? This is the river that has for years changed its course – running wild – building Bihar’s flood plains and irrigating its land. This is also the point where the Kosi meets the Bagmati.

It has a catchment area of 74,930 sq. km., excluding the catchment of the Bagmati and the Kamala, two of its largest tributaries. Dr. Mishra says the Kosi’s course-changing nature has to do with the huge amounts of sediment it deposits from its upper reaches. The embankments have contained the silt and now, at some points, the river runs close to 15 feet higher than it originally did. It is perhaps the only elevated river in the country.

The Kosi, like all rivers, is embedded in folklore and mythology. According to Hindu mythology, the Kosi or Kaushiki was the older sister of Rishi Vishwamitra. Taken by her beauty a demon asked for her hand in marriage. Disguised as a river, Kosi laid down a condition: If the demon could contain her within the Himalayas before the break of dawn, she would accept his proposal. The demon worked through the night building a dam, hoping to contain her. Afraid that he might actually succeed, Kosi asked Shiva to help her. Shiva took the form of a rooster and crowed an early dawn. The demon failed his test and the Kosi continued to flow.

While there are other myths around the Kosi as well, it seems that the most legendary of them isn’t from any particular tradition: It is what is commonly referred to as the ‘1953 Plan’. It is the myth that a river could in fact be held within walls of mud and sand; that the river wouldn’t breach these hastily-engineered embankments. All this not realizing that over a million people caught between the embankments of the Kosi on either side would be damned to generations of annual floods, while those on the other side would always be subject to the threat – or the eventuality – that the Kosi could/would breach its embankments. With the Kosi, the worst is always ‘yet to come’.

A BREACH IS A BREACH IS A BREACH

‘Matsyaganga’ is an official Bihar Tourism lodge in Saharsa town is our base, for beyond this it is hard to find a place to stay for a bunch of 16 people. We head out to a village outside of the embankment, called Manganj (East) in Supaul District that suffered the floods of August 2008, when the Kosi breached its embankment in Kusaha. It killed 587 people instantly, and 997 villages bore the brunt of this breach.

Here we meet two interesting people. One of them is an old man who corners me and asks me in perfect English. “Are you from the Government? Are you from a private company?” When I tell him I am a journalist here to write about the plight of the people after the floods, he laughs a little. “Are you going to give us any free gifts?” He doesn’t tell me his name.

The town witnessed its first ever flood in 2008. Completely unprepared, most families ran away to nearby towns. Some fled to other cities for a few months. It has been more than two years since the floods came and went, leaving everything upturned and broken. The questions of ‘relief’ are most important to them, even though relief here is an elusive concept. Rina Devi, a beautiful woman in a crisp sari, is one of the five sarpanches in the village. She says to us: “We got one quintal of rice, and Rs. 2250. We haven’t cashed the cheques,” she says, “mostly out of anger.” She is disgruntled about how they are treated when they approach the District Collectors’ office for the purpose of rehabilitation. “Those who didn’t suffer the floods have risen. We have had to start from scratch,” she says. Here the issue of whether the Kosi should have been embanked at all doesn’t resonate with them. “Where is our relief package?” they ask. Most questions are relief-centric now.

In this village, as in many others, one member of each family has left for Delhi or Punjab or some other part of the country to work as a farmers, laborer, maid, porters, among several other things. Some villages have witnessed the migration of 80 per cent of their population.

In another nearby village, things are just as grim. We ask some of its oldest residents what life was like before the embankments. They fumble. They say how dealing with the floods came naturally to them. Some others from the village who endorse the ‘tatbandh’ immediately overshadow them, but we can sense that they worry about more breaches. We ask them if they think the embankments are imaginary lines that separate them from those who are caught between them. They agree, but reluctantly. The embankments have benefitted them to some extent, but they know there are many, many who have not. Plus, the floods were the source of natural irrigation, which is no more the case.

We are headed further upstream the Kosi in Supaul District, we pass by broken sluice gates and the town of Givha where acres of land are covered in fine white silt: a tragic, surreal scene. Of all the sights we expected to see in Bihar, the most unlikely one is a landscape of unrelenting white. This white silt and sand, or ‘balu’ has sucked the livelihood out of agriculture, and entered homes and throats as it continues to fly with the seasonal wind. In this village, it seems as if the Kosi left a few moments ago. Some buildings were taken down entirely, but the houses and schools that remain are testimony to the flood. One can imagine how the water might have gushed through these buildings, and left them standing in this half-existent manner, forlorn and waiting to break fully.

It is after dark that we cross the border in Supaul District and enter Birpur in Nepal, where a barrage close to 1,150 meters stands tall. Even though this barrage is in Nepal, it has been built and is maintained by Indian authorities. This is an odd sort of place. We’ve had no difficulty crossing the ‘border’. In the dim light, one can see both Nepali and Indian temples, chai stalls that sell Nepali biscuits, and variants of channa-muri. People laugh and talk and go about their business as usual. We must look strange to them: Grimly observing a barrage they look at every day; this massive contraption out of a movie, which attempts to control the flow of the Kosi downstream. But tragically enough, when the breach at Kusaha (further up from Birpur) occurred, no barrage and no irrigation canal served any purpose, because the Kosi breached the embankment at her whim, with no concern for engineering sense.

THE LAST STRAW: INSIDE THE EMBANKMENTS

The next day promises to be a long one, and perhaps the most insightful one. Before we set out, we stop at the Kosi Seva Sadan in Mahishi, where we are surprised to find a workable map of the rivers of Bihar on a cement platform. We are also surprised to learn that every river in Bihar has been embanked, but perhaps the embankments around the Kosi have done most harm, because of the river’s oscillations.

We set out to a village called Sirwar, which lies about a kilometer inside the embankment. It is actually the first time we drive up over an embankment and cross it to reach the riverbank. The embankments are sandy and have covered up lifetimes in fine white sand. We can still see a remote semblance to routine life, with boards for ‘Masala Beer’ and fried food. Here the difference in the height of the land on either side is stark. Inside the embankment, the land is close to 7 feet higher and reaches half way up the embankment. We find a boat that will take us to the other side. After a short walk, we are in Sirwar, where the first building we see is a broken down school. Inside, as always, the people are hospitable. They bring us tea and sharbat. They tell us that being caught between the embankments is not just a problem, but the kind of damnation they can find no way around. Everything is severely inadequate: water, sanitation, electricity, education, and health facilities. People must walk long distances to work on the fields, there is no assured implementation of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). Here too, one member of every family seems to be in Delhi or Punjab. Women are reluctant to share the problems they face during the floods, but evidently there are quite a few. In a short meeting where Dr. Mishra listens to the people speak their minds an eloquent, fiery man called Ram Prasad, also someone who has been mobilizing people in Sirwar and the surrounding villages to debate the issue of the embankments to the higher authorities. “Kosi ko mukt kar do,” he says somewhere between his long speech about the anxieties of his people.

While we are fixated on the question of the embankments and how people perceive them, we also realize that there are daily troubles to deal with. One of the residents of this village is eager to have his children study in a school that does not function. He feels like there is a mandate on the part of the District authorities to disallow the school from running smoothly. Every time he goes to avail of his free kerosene 10 kilometers from the village, he is asked to come back the next day. Sometimes, he says, he feels like they are being punished for living inside the embankment, when they were not even given a choice in the matter to begin with.

Kavindra Pandey of the ‘Badh Mukti Abhiyan’, the man responsible for our impeccably scheduled trip, says that on his travels inside the embankments he has met people too ashamed of their living conditions to let him stay with them. “They collect snails and eat them, because they cannot afford anything else. They made us leave their village at 4 a.m. and asked us to take the first boat back home,” he says. It almost seems like after the embankments were built a large chunk of Bihar, especially North Bihar, was forgotten.

In Hausilya town on the embankment, which is a Musahar or Mahadalit village, we meet Jameela, whose son works in Punjab. Here the children are sickly and run around with swollen bellies, a sign of beriberi. The only water pump has been installed by the collective efforts of the residents of the village. A few other women join her and show us their NREGA cards. They are blank.

QUESTIONS, AND SOME ANSWERS

What we’ve seen inside the embankments is testimony to the fact that there is an urgent need for evaluating the embankments; to in fact prove that they have controlled floods and improved agriculture. Dr. Mishra’s work, his writings about the problem – replete with statistics and factual data – have spanned many years, many publications and many forums. He is perhaps one of the few people in the Bihar, let alone in the country, who is fully acquainted with the real sorrow of the Kosi: its walled peripheries. Needless to say, the embankments benefit the politician-engineer lobby the most, and any opposition to the embankments would mean disrupting this nexus.

But apart from these very critical issues, there are a few things that sum up the Kosi experience for me. One the most significant is that of an ‘alternative’.

What is the alternative to a problem that has outlived half a century? While this is perhaps a logical question at the end of a trip like this, it is strange that we seek alternatives at all.

There are ‘alternatives’ in that sense: We need a better way of managing silt, better drainage and irrigation so that water doesn’t stagnate as it does. But, surely these are processes that should have already been thought about by the State? They aren’t.

Before we stop to think of these alternatives, we must try to answer a looming, uncomfortable question that precedes all engineering sense and all bureaucratic reason: Is there an alternative to a free flowing river?

It seems that by building the embankments, the elementary nature of a river like the Kosi, its dynamics and relationship with the people has become secondary. It does, in fact, seem that the embankments are what the river came with, before people and before memory.

Is there an alternative to a free flowing river?

If we don’t answer this, the Kosi will.

in an ironic twist, John Haulton,an administrator wrote in 1949, “The Kosi is an impudent hussy who leaves her bed at night and seeks strange beds, and that is why no engineer will willingly have anything to do with her, for fear of his reputation”. For decades an engineer-activist Dinesh Kumar Mishra has been working to educate people and policy -makers on the problems of Kosi and about the difficulties faced by people who are doomed to live under the shadow of an embankment

I do agree with all the ideas you have offered to your

post. They’re very convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are too quick for novices. May you please lengthen them a little from next time? Thank you for the post.