The God of Global Village (An Excerpt from the Novel): Ranendra

Several months passed after the agreement but there were no visible signs of implementation. The bigger companies like Shindalco had filled two or three abandoned mines by the road as window-dressing. Some of the important Asur youths like Rumjhum, Soma and Bhikha were given jobs in the office but they did not look particularly happy. They were humiliated in the name of training. The employers did not care for Rumjhum’s knowledge of history or his Honours degree in Sanskrit. His aim was to work as a Mate with the labourers in the field but he was handed over account books which he hated. Whenever he made mistakes, everyone made fun of him, including the Peon Dubey from the Poddar Mining office and this hurt Rumjhum terribly.

The tanker carrying water to the Pandeyji bungalow at Bhelwapaat now made an additional trip regularly. In the daytime it would remain parked in the Sakhuapaat bazaar. It brought some relief to the siyani folk of the nearby areas in collecting water. But no projects appeared to lift water from any spring, waterfall or stream with the help of an electric motor. The management seemed to have forgotten its assurance of the hospital too.

As time passed, James Lakra and his friends, who had been hiding their faces, were seen on sparkling new motorbikes. If one had become a petty contractor, another had been gifted a second-hand truck. The awards for turning quisling. No boy from the paat ever talked to them. Many a time, scuffles were barely avoided at Budhani’s tea stall. The tension between Kanari and the paat was so heightened that Doctor Sahib had to shift his residence to Sakhuapaat where he lived now with his mother and sister.

There were no signs of the earlier unity or peace on the paat. Pointless fights occurred between the amulet wearing and the other folks. Lalchan had still not overgrown his infatuation with Babaji. Finally, Ram Kumar took stringent measures. Nobody knew more about Baba’s tricks and hypocrisy than him.

He had been escorted secretly from his Kanari residence to the ashram in vehicles many a midnight. So many times he had saved the life of tender aged girls lying in Baba’s room by administering them glucose and water intravenously that he had lost count of the visits. Whenever his eyes fell on the rascal Baba, he felt like spitting on his face. The swine was a pervert in need of mental treatment. Baba lost control whenever he came across a woman, howsoever old, alone. He turned into a wild animal after taking narcotics like cannabis and bhang. His perversions had acquired psychopathic dimensions after the boarding schools were established. He demanded tender aged girls every night to press his legs. It had been going on for years. Who on the paat in the coal bearing region was not aware of it? But nobody dared protest. Everyone was afraid of his sway. Criminals sporting long beards, lounging in the ashram, lost in the stupor of narcotics were a common sight. It was a terror tactic. People were afraid of his authority over the police and the administration. Doctor Sahib ventilated all his frustration to me in one breath the other day.

Doctor Sahib had two nagging issues to stand up for. One was the masquerade concerning black creatures. The cattle of the poor Asurs would not be sold at throwaway rates in the haat. When Lalchan demurred, Doctor Sahib sent a couple of boys to catch hold of a small-time trader from Sakhuapaat. The fellow was put away in a room and beaten with shoes. He squealed quickly how much they had to pay to the ashram for every animal bought. Only then Lalchan saw the light and his craze for Baba abated a little.

The other issue is that there is no protein in the staple diet of the paat Asurs. In the name of pulses, there would be a tiny amount of urad along with sargujja; it was dried in the sun as dollops with gourd or khira. When guests arrived, the dollops would be cooked in gravy and served with rice. Bhaat-jhor. Normally, they filled their bellies with corn or boiled rice only. The only source of protein for them was the mutton bought from the haats held every three or four days or fish caught from some spring. If they stopped taking this, the growth of the children would be stunted and the youth would become emaciated. Hence, it was not wise to turn vegetarian. Finally, it was decided after protracted arguments from both sides that the amulet-wearers would remove their amulet while taking non-vegetarian dishes and put it on after a ritualistic bath.

Ripe paddy has grown luxuriant in the paddy field of Mahua Toli, but the matter has not been sorted out yet. There has been no progress in the murder case or the land issue. The present magistrate has received orders for transfer. The new one has not taken charge yet. One hundred and one excuses of the bureaucracy.

Once again Doctor Sahib has brought the news that the Gonu clan was trying to find ways to harvest the crops. They would reap the crops in the middle, leaving one hand of paddy intact on all sides, to get round legal problems. Maybe they had been given the counsel by the officer-in-charge or by some lawyer. Something had to be done quickly.

The matter had to be kept secret from Balchan but was it really possible? He had just recovered from convalescence. His appetite had barely improved during the last three or four weeks. The shine and the laugh had just come back on his face. Nobody wanted him to take him a rash step in anger. The family’s finances had suffered badly in his medical treatment. They were not yet ready for another trouble.

This night Balchan stole out of the house silently. Nobody suspected anything at home. Not even his Gomkain lying by his side. God knows what he did but the first stack of paddy crops lay in the barn at the door before dawn break. Some whispered that he had taken the help of his mates from the Jungle Party. Others said he had gone with his friends after collecting the ash from the cremation grounds. He blew the ash towards Mahua Toli and the whole village fell in so deep a slumber that nobody heard even a creak. Whatever, their paddy came to their house.

*

Lalchan Da informed me that Lalita had come home during the vacation after writing her exam. On the way she had made a visit to Kavita and Namita in their school. They looked ill, so she brought them along. They won’t tell, but their aunt said they had a fight with someone in the ashram. Go ask them, maybe they’ll tell you.

On Saturday night I went to Amba Toli as usual. Rumjhum kept away from me. Maybe it was the pressure of his job in the Poddar mines or perhaps it was Gandoor’s complaint. The job was really a pain for him. I didn’t want to aggravate his troubles. Soma and Bhikha told me he was always drunk on mahua nowadays. He had become an alcoholic, bunking office frequently. You never can tell, this bloody Poddar might chuck him off any day.

Lalchan Da, Doctor Sahib, everyone was sick of Rumjhum’s growing addiction. They knew the reason. Rumjhum had told them about every little attempt in the office to humiliate him. He had quoted the venomous jibes of Mishraji, Vermaji, and the peon, Dubeyji. He should have nipped the problem in the bud. Now things had gone too far.

Lalchan Da recalled the conversations this day, regretting that if everyone had taken the manager of Poddar mines to task in the very beginning, Rumjhum could probably have got his favourite job in the field. Things would not have come to this pass. Only last night he bruised himself badly after slipping and falling on the trail to his home at Kandapaat, hurting his head.

Lalita came in with the tea just then. Lalchan Da had told me quite early that although Lalita was his niece, yet she was more than a daughter to him. His elder brother and his wife had died of malaria the same year. First, his brother, then his sister-in-law, within a span of six months. Lalita, hardly fourteen, was studying in the seventh grade then. She was a studious girl. After the death of her Ayo and Baba she turned introvert, losing herself in books. Naturally, her aunt’s fondness for her grew. They took care not to hinder her studies. When she was in tenth and then in eleventh, Rumjhum came home regularly to help her with her studies. She had passed with excellent marks. Now she is doing M.A. But she is still a very silent girl.

When did she come? When did she greet me with a johar? When did she return having served us tea? I did not remember anything. I simply kept staring. On the paat at least, I had never seen such a cultured, decently attired, comely girl. She was not quite fair like Lalchan’s other children and his family but her wheatish complexion had a beatific glow. Taller than the average, slim, a grandness of bearing reminding me of someone from history. I tried to recollect, I had read a book recently about the possessor of such a personality. In a moment Pocahontas came back to me.

The English founded their first settlement, Jamestown, in old America in Virginia in 1607. But the aboriginal Red Indians disliked their activities. The Red Indian chief, Powatan, imprisoned one of the senior English army officials but the day he was to be hanged, Princess Pocahontas saved the captain’s life. She helped the British residents of Jamestown secretly many times. She saved their lives but they imprisoned Pocahontas by tricking her with an invitation to their ship. She was forcibly married to an English trader, John Rolf, a widower and was taken to London. London went crazy over the royal demeanour and graceful aura of the princess. Sir Raleigh came to visit her. The poet, Ben Jonson, gazed at her for hours. He could not even speak in her presence. But this daughter of Nature could not tolerate the polluted environs of London for long. She contracted T.B. and passed away at the unripe age of twenty two.

On the other hand, the English almost wiped out her community after Powatan’s death. Their population dwindled to a measly one thousand from eight thousand. They too scattered and perished in the course of time.

Why did Lalita remind me of Princess Pocahontas? Was it a signal from Destiny? Was Lalita’s Asur community also going to scatter and perish? Why this apprehension? Why did my left eye start twitching?

Lalchan Da’s Baba called him in. I took out a magazine from my bag and started turning the leaves. Just then Lalita came out with Bhauji. They wanted Kavita and Namita to be admitted at the Bhaunrapaat School once again. Bhauji told me that Lalita was not willing to send them even for a single day to the Koeleshwar school. God knows which bearded disciple of Baba had crossed Lalita’s path. He started molesting her in the name of offering blessings. There was a huge ruckus when she slapped him. The girls too look sickly. They neither eat properly, nor are their own self. What will their grandfather say if he comes to know? You please take him to Doctor Sahib for a medical check up.

When I passed the courtyard and entered the room of the girls, I almost failed to recognise them. Their faces had withered; they had lost a lot of weight. Sunken eyes. Dry lips. They looked as if they had been ailing for months. My first thought was to summon Doctor Sahib.

Doctor Sahib realized the seriousness of the matter instantly. He started grumbling that even a witch keeps off at least seven neighbouring households but this rascal Baba is a fiend. He must have called these girl children to press his legs at night. Girls turn into stone after such shocking incidents. I have already seen dozens of such cases in the ashram. The bastard has gulped down all his sense of shame, disgrace and fear.

Muttering, he collected medicines, injections and vitamins and rode the truck with me. He talked with the girls alone. His hunch was right. Their tender hearts had been traumatized, leading to their loss of appetite and peace of mind. They saw the naked demon Baba everywhere. The only treatment needed was loving care and understanding, and the medicines to induce sleep and appetite. The nursing duties were explained to Lalita.

Standing away, I felt Lalita was asking Ram Kumarji about me. I don’t know what he told her but at least now she did not look wary of me. I sensed some warmth in her eyes.

*

The treatment proved helpful. Kavita and Namita grew well in a few weeks and were readmitted at the Bhaunrapaat Boarding School. Lalita took the girls personally into the chamber of the Head mistress and completed the formalities. I didn’t have to do anything. At first, she escorted Kavita and Namita daily. She would send them into the classroom and sit for a while with Madam Minj. I came to know that she had been her favourite student. A couple of days later it came to light that she would take classes at school during her stay at home in the vacations. It was well for Rumjhum played truant after three every afternoon nowadays. But Etwari did not look happy at all. Her eyes hardened whenever her gaze fell on Lalita.

The frequent meeting in the school broke the ice between us. Moreover, everyone doted on her honey sweet voice. Everybody was eager to talk to her, except Etwari, whose look and manners showered glowing embers.

Lalita was pretty angry with her uncle Lalchan ‘Ka’. She believed that men, especially Asur men, were quite gullible. Anyone can dupe them easily. They have not learnt even from their lore. She really had great expectations from her Rumjhum Kaka. She thought he was much more intelligent than her classmate Sunil Asur, emphasizing that there was no comparison between Lalchan and him. She made several attempts to meet him. Once when she went to the Poddar mines office at Sakhuapaat, the staff members started staring at her and whispering in quite a funny manner. She felt they took her to be a new animal in the zoo. That mulish Dubey crossed all limits of decency and burst into an obscene Bhojpuri song. The rest of them were no better. Men old enough to be her father and grandfather—flabby, sagging, elderly, Mishraji, Sinhaji, Verma, Sharma and Guptji—started acting in a weird manner. One kept grinning, one started talking in whispers, and one suffered a non-stop bout of coughing. One of them took out his purse to flaunt currency notes at her. God knows what they took her for! Was she the water-maid in their residences or Ramrati? She sat at Rumjhum Ka’s table hardly for three or four minutes. She felt her head would burst or else she would catch hold of one of the goons and beat him black and blue. The molten iron running through her veins had not turned into water yet.

Sometimes, she went to Kandapaat to talk to Rumjhum Ka but he was never in his senses. Rumjhum Ka’s Ayo held her close and wept to see his fall.

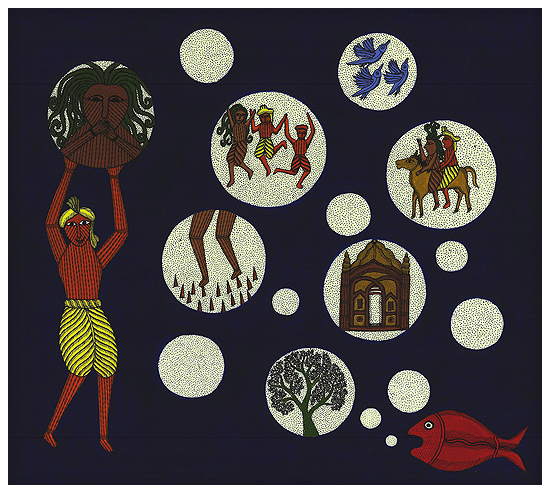

Lalita often tried to rediscover her old Lalchan Ka who used to come eagerly daily to teach her diligently as if impatient to pour into her all the knowledge of the world. Each piece of information brought by him was brilliantly novel and sparkling. Opening new portals of light every moment. Lending thousands of wings to her fancy. With the help of which she would plunge in the journey through time. She would be here only bodily, her imagination would soar to new horizons. She would tour the whole world, all the while sitting in Amba Toli. She could clearly discern the features of all the countries and the continents. All civilizations danced before her eyes as if in a T.V. serial. Every subject would become pleasurable and light like dew drops, and then it became hard to believe that Rumjhum was teaching her, not narrating a grandmotherly fairy tale.

She was keen on discovering the old Rumjhum Ka but each failure of hers turned her further inward. When she felt she would go crazy if she did not let someone into her thoughts, she turned to me. Probably, our daily meetings had made her trust me. When the possessor of a personality as graceful as that of Princess Pocahontas began to bide time to converse with me, it was natural for me to swagger. And if I felt helpless like the poet Ben Jonson, it was not my fault. When she sat by me, a fragrance would waft in the air. But when she was agitated, she would talk so animatedly that heat waves appeared to emanate from her as if molten metals were flowing by—a heat so intense.

One Sunday in Amba Toli, she seemed to be in a very happy mood as if she wanted to pour away all her frustrations through a new interpretation of the Sing-Bonga legend. ‘What’s this Sing-Bonga legend? Sing-Bonga assumed the disguise of a khasra boy not only to fool the Asurs but also burnt them all to cinders in the furnace. However, it can’t be taken literally. The Asurs were killed in the battle by fraud. The remarkable fact is that only the men from the Asur community were duped, not the women. In the tale too, the Asur women act wisely and put up resistance. They hold the legs of the flying Sing-Bonga to make earnest efforts to stop him. But they have to pay the price and are mentioned as witches and ghosts in the legend.’

‘At present too, this amulet movement, the fire-homage, the hymns, this naked Baba—what’s all this? Is not Kaka deceiving himself in spite of realizing the truth? We are Nature worshippers. Our Lord, All Compassionate Mahadeva, is not Langta Baba’s god. Our Mahadeva is this hill. This paat, which sustains us. Our Sarna Mai suffuses not only the Sakhua tree but the entire flora. We relate all creatures with our gotra. We respect even the smallest insect; we don’t simply have the concept of the ‘other’. The community which has nurtured such a beautiful concept, what need does it have to seek the shelter of Langta Baba or any other fellow? But no, whenever a new chap arrives here, he tricks and converts us. Still we have the gall to claim we are Asurs with breasts of steel and arms of arkantha. When we mention our ancestors, we deify them to lofty heights by talking of iron smelting, and steel running in our veins. Right up to the crest of the tree, but when we fall, we realize that in reality there is not even water running in our bodies.’

‘What was the relevance of this movement? We went to jail. There was an agreement. Where are the clauses? Where are the murderers of our Aja (grandfather)? Have we got possession of the paddy field? Are the abandoned mines being filled? Shindalco has given up even its charade of filling them. Only a couple of them have been levelled. Is there any sign of the hospitals being started? Is the calamity of cerebral malaria over? On this date too, thugs and contractors are taking the thumb impressions of the Asurs and Oraons on plain paper to perpetuate illegal mining. The exodus of our girls to Delhi and Kolkata, to the residences of Mates and Munshis is on the rise instead of decline. What was the benefit of going to prison or wearing the amulet?’

‘Master Sahib, you claim to be Kaka’s close friend. Go ask him. Is he going to do something or do we have to take up the cudgels?’

Lalchan Da did not utter a word in the desi cabin. Rumjhum lay on the bench in a stupor. It was hard to say whether Soma and Bhikha too were in their senses or not. Lalchan Da bowed his head and never raised it. Tea was served and sipped with lowered eyes. Finally, when it became unbearable, I broke the silence. Lalchan Da began to speak in a low voice, like a gambler who had lost everything, as if the agony was beyond his tolerance.

The C.I.D. report of Chacha’s murder has not come in yet. Nothing has been done in the paddy field case of Mahua Toli. ‘Many a time I reminded Shivdas Baba that there has been no follow up on the agreement. The mines owners are doing nothing. They filled a mine or two only to put up a show and then the work stopped. The hospital and the potable water are nowhere in sight. They have provided employment to a few of us but the men and their jobs are a total mismatch. They did it deliberately so that they might kick us out whenever they like. But the rascal Baba just nods or begins talks of another fire-homage on the paat or of some land deal for starting a school at Amba Toli Neem Taand.’

‘We were duped by him.’ Soma continued.

‘Let bygones be bygones. It’s no use beating about the bush. We shall move ahead now on our own strength. Paat Devta will support us. All the Asur-Oraon-Sadaan villages have to be brought together for this purpose.’

Lalchan Da’s optimism had not deserted him fully.

We were summoned to Doctor Sahib’s clinic right on cue. A moustachioed, obese man with the looks of a sneaky politician, no older than Doctor Sahib, was sprawled in the chair. His breath was foul. The betel juice had trickled in print like patterns on his kurta. Exactly like the fellow described in the song from the film Guide. ‘Sanwari suratiya, honth laal-laal’—dark visage and red, painted lips. On the whole, a flaccid, joker like guy. Doctor Sahib introduced us, ‘This is Guptaji. He was my classmate in the college. He has joined politics and now works for Shivdas Baba. He’ll explain everything.’

‘Hey! Don’t mention the word ‘work’. If an important person like me has to wield a hoe, what will a Kol idiot do? We shove our hands down the throats of these mines owners to snatch away whatever we want. Baba tells us to extract two rupees, we nick off four. Baba’s demand goes to Baba, the remainder is mine. Thirty eight to forty thousand, the monthly payoff is fixed for each mine. Fixed! Do you follow?’

We listened agape. It was bizarre. Finding us silent, he resumed, ‘Hey! Doctor! What a bunch of nincompoops you have brought! Has my standard gone so low that I have to talk to such rustic dolts? I don’t encourage such folks. However, I am ready to do anything for your sake….’

It became intolerable. Another curtain had risen. We all were in the same boat, utterly defeated. Our lips were pursed. With bowed heads we returned to the cover of Budhani Di’s desi cabin.

Right at this moment, Rumjhum stirred and got up. At first he smiled at us and then broke into a laugh. We were afraid he had gone off his rockers. He stood up on the bench and began singing a song. It was a melancholic number, casting a net of sadness over us. The lyric quivered in the air:

‘How shall we spend the rest of our days

It is pointless

Our night

Assures us it will be a sinister, gloomy night

Not a single star glimmers on the horizon

Sad winds

Lament somewhere far off

On our heels

Treads our Nemesis

A wounded deer

Hearing the running steps of his hunter pursuing him

Readies itself

For Absolute Death.’

We shivered to our core. Stunned. The bleak future loomed over us. I recalled it was a song from the book about the Red Indians. A song sung in 1686 by the well known Chief of the Red Indians, Seattle. Still, I felt it sang our present and future.

*

‘You smell of a woman, teacher.’

It was Lalita. We were sitting together by a small hill spring on the wooded incline near Amba Toli. Like Columbus, we had stumbled upon a unique, lovely isle amid the swift currents of time like this mountain brook and christened it companionship. We thought and spoke like twins. It often happened that Lalita would mention first the thought rising in my head. When I told her I was musing over exactly the same matter, we would break into hysteric peals of laughter. All our differences were swept away in the swift gush of guileless hilarity.

But what reply could I give to such a question? No sooner did Lalita start coming to the school, than the manners of Etwari changed. The eyes that used to shower burning embers at first, had gone expressionless now. Her female instinct had foreseen the discovery of the lovely isle much before me. She tried to avoid me but the children and Gandoor behaved normally. They would come to my room to do their homework or to watch TV. Only Etwari had ceased her visits and stopped talking to me. Gandoor appeared happy. I too was relieved.

How did Lalita catch a woman’s scent from my body? I could not figure it out. So, I just smiled.

‘Look here! The scent pulls and repulses us girls at the same time. What’s the mystery? Are you in a live-in relationship?’

The words ‘live-in’ sounded awkward in this secluded wooden spot. However, Lalita told me that the practice was new only for our modern society. It has been an accepted part of life in tribal communities since ancient times. If there is a hitch in marriage, the boy and the girl can live together. However, it was crucial to perform the marriage rites before a son was married off. Sometimes, the parents get married first, followed by the wedding of the son or the daughter, under the same marriage canopy. If they come to live together owing to financial problems, the betrothal is performed as soon as they collect enough money. Inarguably, the fashion of living together has percolated from them to the modern society.

But Lalita’s query still dangled in the air: whose scent is this; what riddle is this?

I protested vehemently but she was not ready to listen.

She was shaking her head in rejection when the spirit of the poet, Ben Jonson, alighted softly in me. I gazed at her, oblivious to everything else. Words faded and sounds disappeared. Time ceased to flow. Space and epoch became meaningless. Only my eyes quenching themselves, consuming her visage. I saw a dusky rose swaying on the branches. The soft rose is now captive in my fist; I want to carry it to my lips. And then it was not a rose but a green, sprawling hill in whose woods I was roaming about. The moon descended and perched atop the Mahua branch. With each movement of the moon, the mahua blossoms trickled down…drip-drop…drip-drop.

The cosmos acquired worth from the dusky rose, this slender lunar sliver resting on the mahua bough; without it the world was meaningless. The amber of the sun, the coolness of the moonbeams, the gush of the streams, the quaintness of the earth, the crimson of the buds, the jade of the leaves—all obtain sense and significance when they mingle with her. If she is not there, the universe ceases to exist.

Just then someone clapped and my reverie broke. She guffawed when I blushed. ‘We are going to be fast friends. Come on! This very day we declare each other our sahiya.’ Sahiya, or becoming friends through a formal declaration, was a minor ritual.

Lalchan Da too laughed. ‘So far I have heard only of the boy-boy sahiya or a girl-girl sahiya. Lalita is initiating a new tradition, a new practice. That’s good. Lalita has selected a buddy like herself, a book worm. A sky gazer. A fine thing it is.’

He appeared really happy. Every member at his house was pleased except her Baba.

Bhauji explained to me that the ritual entailed some expenses. Sahiya is a formal affair. Gifts and souvenirs have to be exchanged. You won’t get things to the liking of Lalita in the haat-bazaar here. Go visit the town. The rites will be performed this very Sunday.

It was a short event. I gifted her cloth pieces for a salwar suit, and a pen set. Lalita had brought a nice, readymade shirt for me. Then we exchanged gulainchi flowers. Henceforth, we could not call each other by our names but only as ‘phool’ (Flower).

Lalchan Da had a goat slaughtered. All the boys and girls of the community enjoyed a hearty meal and then skipped to the beat of the mandar all night. They would often pull me in but I failed to find the rhythm, stepping ineptly. Finally, I sat down by Lalchan Da.

What was this jhoomar dance? Moving in a semi-circle, bowing, advancing, then throwing the head back, retreating. Like a breeze billowing the green paddy crops back and forth. Like the bamboo grove swaying supple, sportive, joining the movement of the wind. Like waves in the rivers, rising and falling sensuously. Swarms of birds in the sky returning to their nests. Nature herself in her primeval form became one with the divine swing of the cosmos. The moon set. The night, like a blanket soaked in dew, grew heavy. Everyone was swaying. But the call of the cuckoo resonated in my ears, ‘Hey, phoool!’

*

The atmosphere in the Thursday bazaar at Sakhuapaat appeared rather low. The usual smiles were absent from the faces. The whispering groups here and there looked sinister. Things became clear when Lalchan Da entered the desi cabin. ‘The Forest Department has served notice to thirty seven villages to vacate. Some new fangled project of saving wolves it is. They are calling it ‘abhayaranya’ (Sanctuary). If the word itself is so difficult to pronounce, you can imagine how complex the real thing would be. Of the thirty seven villages, twenty two are of the Asurs, the rest belong to Oraons, Kherwars and Sadaans.

A hush fell.

‘They’ll kill human beings to save the wolves?’

‘Is it a project or a plan to kill us?’

‘Were there no problems earlier that this one has been added?’

‘When troubles come, brother, they never come alone.’

Beads of perspiration broke out on every forehead. Nobody spoke, bowing their heads to mull over the new crisis. Just then Rumjhum, still high, opened his eyes. He stood up to repeat over and over the same lines of a song, as if the needle of a gramophone had stuck on the record:

‘The pounding of the hunters’ boots

Can be heard distinctly

You cannot be saved

Wounded deer

You cannot be saved.’

Defeat overtook every face. Lalchan Da hauled Rumjhum down. Lemon tea was brought to diminish his tipsiness. It was decided that a meeting should be held at Amba Toli the following day. All the baiga-pujar, pahan and the boys who know how to read and write should attend. Information should be sent to the affected villages. This time the battle will have to be fought on their own strength.

In the midst of the discussions in Doctor Sahib’s clinic before the men left for Sakhuapaat in the evening, a message from Shivdas Baba was brought by one of his disciples who had arrived in a truck. He wanted the Centre’s plan for the wolf sanctuary to be opposed at any cost. Baba too would join in the resistance.

They were surprised. The people of the paat and Lalchan Da hardly ever went to Baba’s ashram these days. They had taken their children out of his school one by one. No fire-homage ceremony had been performed for months. People had almost forgotten about starting a school in Amba Toli. Many of them had taken off their amulets too.

‘What has bitten this rascal Baba now? Why this sudden concern and sympathy?’

There were a number of doubts. The task of finding out the answers fell on Doctor Sahib’s shoulders.

Doctor Sahib came back with the information that the Forest Department had sent a report years ago that earlier, the population of the wolves in the sixty four square kilometres used to be seven hundred and eighty eight but now it had fallen to one hundred and seventy six. Thirty three pages of the report have been devoted exclusively to this unique sub-species of the wolves, with the conclusion that they must be protected. The Forest Department has always considered the Asurs and the tribals encroachers on its land. It is not ready to hear that people have been living in these forest villages for hundreds of years. The Forest Department has made a late entry. Like the flora and the fauna, the men here are the natural inhabitants of the forests. But the education of the Sahibs tells them differently and now they are hell-bent upon the removal of the villagers. Another important revelation was that the contract of barbed wire fencing of the sanctuary had been bagged by a multinational company called Vedang. Such a huge company has taken up such a paltry contract, it seems rather strange. For years, the talk has been going on that the processing plant for bauxite should be located here instead of the ore being carted outside. It seems Vedang is coming to have a sniff. Vedang is a top-echelon deity of the global village. It is like the camel and the Arab’s story. The company actually comes from a foreign country but it has taken up a purely Indian name, ‘Vedang’. This shows how shrewd it is!

The rascal Baba is interested because the local M.P., who is also the State Minister for Forest at the centre, does not let him come close. Babaji had asked for funds from the M.P. quota to start a school but M.P. sahib overlooked it. It has happened several times. That’s why the rascal Baba is livid. Another fact escalating the tension is that the two belong to different political parties. Vidhayakji has planned to contest the M.P. election this time. Another fact is that both the rascal Baba and Vidhayakji are truly sly. They must have got a sniff from the signboard of the company, Vedang. There is big money involved in it. That’s why they have planned the protest.

We don’t have to get into their muddle. We must begin our battle and take care this time to not get arrested. The police station will definitely declare us Naxalites. Vedang has bribed them well.

The elders, baiga-pahan, pujar-mahto from all the affected villages assembled in the meeting at Amba Toli. A new slogan was added to the standing demands, ‘We shall die but not hand over our lands.’

Mines stopped, work struck, transport of bauxite ceased. Naturally, anxiety gripped the deities of the global village once more.

*

The Patharpaat outpost was teeming with policemen. Armed forces were everywhere in the area. But Lalchan Da, Doctor Ram Kumar and their colleagues could not be traced. The administration was on the horns of a dilemma over the pressure exerted by Vidhayakji and Shivdas Baba.

Lalchan Da’s ‘Samgharsh Samiti’ imposed a janta curfew on the paat. It was impossible for the police to venture into the villages. They enter houses on the pretext of making arrests and molest the daughters and daughters-in-law. Sakhua trees were chopped down to erect check posts at the entry point of every village. A barricade made from a thick log, covering the width of the road. Stone weights tied to one end, the other end pulled down with the help of strong ropes and tied to small stakes. There was no question of a vehicle passing through. There was room enough to let in men, cattle or a bicycle on the flank. The check posts were erected in front of the houses of the Samgharsh Samiti members. If a police jeep ever came at night, the policemen had to stop to open the barricade. Loud drums would start beating in the house and all the men and women of the village would gather within ten minutes. They would sit silently before the jeep. Sometimes, a havildar or a sub-inspector would swear at them or goad them with his stick to incite them but the silent and peaceful demonstration always compelled the police to go back.

The battle was being fought on the strength of Lalchan Da but he was now a ghost of his old self. He had changed—the murderer of his uncle had not been arrested yet, his finances had suffered terribly in Balchan’s treatment; added to it was the humiliation of the daughters at the school. His laughter had vanished, the glaze on his forehead had diminished. He paid scant attention to the cleanliness of his clothes now. The confidence of belonging to the most prominent family on the paat, of being influential, had been shaken badly.

Because I was Lalita’s sahiya now, my visits to Amba Toli had become more frequent but Lalchan Bhauji did not sing the brother-in-law – sister-in-law song any more. My sahiya would often hum the Phulchar spring song but could phool ever replace bhauji?

Lalchan Da, maybe, was feeling lonesome also because of Rumjhum’s growing addiction. Doctor Sahib was occupied in his profession. Wherever he went, the sick and the ailing from the paat hunted him out. He had to take care of his mother and sisters too. Soma or Bhikha could in no way replace Rumjhum. The only person, who could fill the gap, was my phool. But Kaka and the niece had never opened their hearts to each other. Since her childhood she had never sat with him to talk freely. Everything was conveyed by Kaki. How would she dare to confront him directly? She was not old enough yet, so she sat at the back in the meetings and gatherings. Budhani Di tried many times to make her come to the front rows but she never agreed.

The other day, Rumjhum and Lalita came to my room before I left for school. A year ago, Rumjhum had turned a complete alcoholic. I had heard that he used to rinse his mouth in the morning with the first produce of mahua. His Baba does not live in Kandapaat. He stays at the school where he is posted, twenty miles away. Sunil never comes from the university hostel. Ayo cannot scold him; she can only mope, finding her son growing distant and emaciated. When Baba comes on Sundays, Rumjhum keeps away.

Today he was not drunk probably because Lalita was visiting him. He sat silently for a while and opened his mouth only after finishing the black lemon tea prepared by her. He said he needed the fax number of the Prime Minister office. He had summoned Lalita early in the morning to get a letter written to the Prime Minister. My eyes filled with tears when I read it. A gasp rose in my breast. It must be sent to the PMO. But finding the fax number was not an easy job.

More than a week of the strike passed. The visits of senior officers on the paat became more frequent. The vehicles of the Shindalco Manager Pandeyji and those from Vedang kept roaring to and fro. Who can give me the number? I was at my wit’s end. Rumjhum suggested I could get it from M.P. Sahib. He has some five odd pages full of official phone and fax numbers.

Right! Absolutely right. Who says he has gone off his rocker! There were more facts in his letter than came within the ken of daily readers of newspapers like me.

The handwriting in the letter was really beautiful. Rounded letters—like pearls. I did not know the handwriting of my sahiya was as charming as she was. But the matter in the letter was quite depressing, full of horrifying realities:

Respected Prime Minister,

I had to fortify myself to write this letter to you. I have always been an admirer of your honesty and simplicity and have always thought very highly of you. I have been listening to your speeches delivered on Independence Day and other occasions, broadcast by Akashvani.

You have accepted candidly the fact several times that people outside the market system have not been able to reap the benefits of this economy. You have been talking of lending a human face to the system, shining a ray of hope in our hearts.

Sir, maybe you know, our Asur community has been searching for the human face of governance for thousands of years.

When our ancestors took a vow to save the forests, they were called demons. When they resisted the burning of forests to expand farming fields, they were dubbed wicked fiends. They were attacked and chased away repeatedly.

But the defeat of the Asur community in the twentieth century has been our biggest rout in the whole of history. This time, not the Sing-Bonga of our legends but companies like TATA have ruined us. Steel, hoes, trowels, digging bars and pick-axes made in their factories reach even far off markets. Nobody now pays attention to the tools made from the steel smelted by us. Our thousands of years old expertise of smelting steel has gradually disappeared.

In desperation, we took to agriculture by ploughing the bosom of Paat deity. However, legitimate and illegitimate mines of bauxite are swallowing our land like a giant python.

Our daughters and our land are being snatched away from us.

Where shall we go now? It is beyond us to divine.

Once I went to a slum near the university in the capital. I saw human beings, but they carried no faces. They were nameless. Their identities had been lost. I was beside myself with fear to see faceless human beings, sir. I ran off in terror.

Sir, maybe you know that there are hardly eight to nine thousand Asurs left alive now. We are scared. We don’t want to become extinct. The wolf sanctuary will save the rare wolves, sir, but it will wipe out our race.

Truly speaking, we don’t want to be faceless beings, sir. Rescue us, sir. You are our last ray of hope.

What more can I write?

Yours truly,

Rumjhum Asur

Kandapaat, P.O. Kanari

P.S. Koelbigha

Dist: Barwe, Kikat Pradesh

My heart grew heavy as I read the letter again and again. Tears welled up. I vowed silently that this letter would reach the P.M.O. office, come hell or fire.

(Translated by Rajesh Kumar)

Global gaon ke devta kee sameexa maine bhi abhi hal hi me likhne kee dhrishta kee hain,maine is novel me paya ki lekhk svya is upnyas ka kathavachak hai jisne latoor,lohardagga xetr ke jvalant smasya ko ujagar karne ka praya kiya hai