The Believer: Meraj Ahmed

It was the third time I’d met him, but it felt like the first. I’d gone twice before to Saud’s to find him, but both times I was so tired from running around all day that I fell asleep before he got back. The next day I waited around, but when he still wasn’t up by mid-morning I decided to leave. His sleeping-in made me feel strange—adults get up before the birds start jabbering in the bushes, and yet why didn’t he?

Looking at Babaji’s white hair and wrinkled face, you would guess that he was sixty or sixty-five, and so it was natural to be curious about what all he might have experienced in his long life. The first time, just before I had to leave, I tried to ask Saud about him, but he responded angrily, “Leave it, will you. He’s a crazy old coot.”

On the second occasion Saud repeated himself and added self-consciously, “You know how I am—he’s even worse. He comes and goes as he pleases and doesn’t care about the room. Sweep? Forget it. I’ve been paying for both of us for the last two months. He has two houses across the Jamuna. A wife. Kids. But here he is, driving me crazy! He knows everything about how to run a bakery, but who knows why he’s trying to reinvent the wheel at his age …”

I wanted something more than this. I don’t know why, but I felt like he was holding something back—something that would be worth hearing.

And he was.

“It’s been years since he’s eaten a meal,” Saud told me. “During the day, just tea, and then at night he’ll eat two pieces of bread with a glass of milk. That’s it.” He told me this much to get me off his back and then returned to cursing him out, “You can get the rest of the shitty story from him. But he has to be in the mood. You know, I’m already sick and tired of him. I’d kick him out, but it won’t be easy to find another roommate.”

While Saud calmed down, I thought about how people say that many sadhus and fakirs make it through their entire lives without ever really eating, and yet Babaji was neither a sadhu performing ancient rituals in the forest nor some fakir hanging around a saint’s shrine. He was only an old man who shared a room with my friend Saud; an old man who no longer cared about anything, least of all the way he looked; an old man with a stained shirt, scraggly beard and disheveled hair; the type you can find absolutely anywhere. What was special was how he hadn’t eaten a proper meal for years—this made him unusual and increased my curiosity. I wanted to know more, but Saud wasn’t in the mood to tell me.

In my third visit I was finally able to talk to him. I happened to go over to Saud’s very late, and this time Babaji was already there. The restaurants nearby had already closed for the night, but the sweetshop where Babaji got his nightly bread and milk was still open. Saud got back and the three of us went over.

Walking there, we talked about this and that, and right as we got to the sweetshop I couldn’t stop myself from asking, “Babaji, is it really true that you haven’t eaten a meal for years?”

He smiled briefly. It seemed like he had anticipated my question. But then his smile faded and he looked sad. He sighed deeply, and I thought that he might be about to answer. But he didn’t.

“Let it go, bauji,” he said dismissively. “What should I say?” Then he changed tack, “I thought you’d never come back. Finally we get to meet! Saud’s missed you.”

Then our milk and bread was ready.

“But you didn’t answer my question, Babaji,” I said. To add weight to my request, Saud explained, “Baba, he writes stories. He wants to write about you.”

Saud was in a light-hearted mood, otherwise he might not have helped me like this. “Stories? Like in the newspaper? In books?” An eager look spread over his face. “Yes, but not just that. Even Nirmala will read it,” Saud said, goading him on.

As soon as he heard Nirmala’s name, his face softened with sadness and a strange twinkle lit his eyes. “Okay, then a glass of milk on me,” he said.

Saud and I tried to dissuade him, but he went ahead and bought us both a glass. “So my story will reach each and every village in India?”

“Yes, but beyond that too,” Saud said sarcastically. “It will reach the very ends of the earth!”

Babaji didn’t say anything, but you could see the idea pleased him. “Alright then,” he answered. “If that’s true, then of course I’ll tell you.”

And he began to tell his story, “You must remember. It was back before Jawaharlal and Gandhi took power. It was a brutal time…”

Not only was this before my time but the era he was talking about was when my father was just learning how to put on clothes. Before Saud could interrupt to point this out, I encouraged him to go on, “Yes, yes, I remember.”

“Everyone was leaving the villages. We had to leave too. Everyone was talking about going away. I was nineteen. Just a teenager. But my father—he was very athletic and everyone had heard about him. People were leaving everything they had. By the time we got here we had nothing, and my father lost confidence. He said we should stop. He started worrying that they wouldn’t go ahead and make Pakistan. Anyway, then it was just a rumor. My mother kept insisting that we go with my father’s brothers, but who was going to stick up to my father? We stopped right on the other side of the Jamuna. My mother already wore saris and my father, a dhoti. They dressed like Hindus. I didn’t want to wear Hindu clothes but my mother forced me.

“Finally we had to do something to put food on the table, and that’s when I got a job in the cookie bakery here in Delhi. We had to bake at night, so I didn’t hardly ever go home. Everyone was still tense about everything when one day one of the men at the bakery saw me bathing outside. I usually bathed wearing clothes but that day I happened to be wearing only a towel around my waist. The man suspected I was Muslim. And I was, through and through. Everyone started accusing me of being Muslim. For a while I took my mother’s advice and lied, but I knew I couldn’t keep it up forever. After two days, I told them the truth.

“What do you think, bauji?” Babaji asked me. “How long could I’ve gone on pretending? We’d been honest about it from the start. Before we left our village, some people went up to my father, ‘Khalifa, you guys barely pray. Why don’t you convert?’ It was true we weren’t the most observant Muslims. My father had already been thinking about that. But I said very straightforwardly, ‘So what if we don’t pray and fast? We were born Muslims, so let’s stay Muslims. Changing names won’t convince anyone. Anyway no one will care in a hundred years.’”

Babaji drew in his breath deeply and then continued, “What a time that was. I’m from the weaver caste—I’ll admit that. But no one in my family or extended family has any connection with that sort of stuff. We had a field. We had a good house and an orchard, you know? Back in our village and the villages around us there wasn’t anyone my father hadn’t beat in wrestling—not even from the upper castes.”

It seemed like Babaji was drifting away from the main story, but before I could say something Saud interrupted to lead him back, “What happened after people found out you were Muslim?”

“What’d you think? When you’ve already been forced from your hometown, what’s moving one more time? We got out of there before the high-caste-types could find out. I lucked into a job as a watchman at a Sikh’s house. It was God’s will. The man of the house was very generous. They did business from here all the way to the Panjab. I hardly had to do anything. Push their beautiful little girl around in a stroller in the morning and evening. Walk their boy to school and back. Their mother sometimes teased me that I should play with them more. I didn’t tell anyone I was Muslim. My mother insisted ….” he lapsed into silence.

“Then what, Babaji?” I said to get him going again. “When did you flee?”

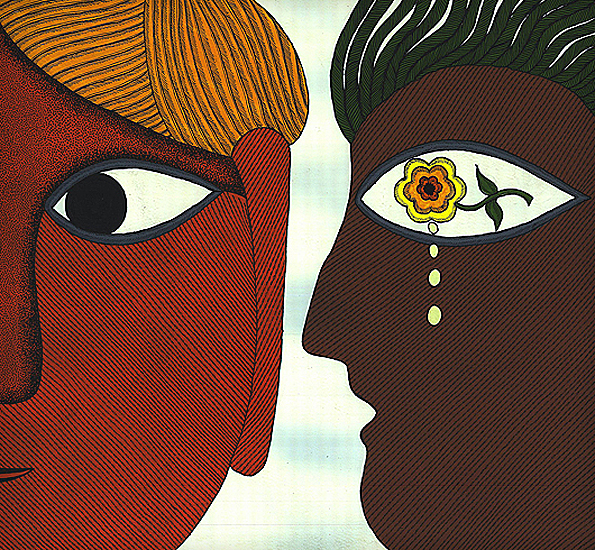

“That wasn’t yet. This was still before that. The family of the brother of the mistress of the house came. Her brother, his wife and Nirmala.” At the mention of Nirmala’s name, an unusual sparkle lit Babaji’s eyes just as before. Then it left, and he fell silent. It was hard to say whether he was happy or sad. In any event once he heard Nirmala’s name, Saud became a little more interested in Babaji’s story: although he had heard Babaji mention her name before, it must not have been in connection with this story.

“Then what happened?” Saud asked, looking deeply at Babaji.

“Nirmala! Her body was as beautiful as the kurmi girls who live around here. She was lithe and young. Fit. No, there’s no comparison. How can you compare a dove to a crow? Kurmi girls are dark, but her skin was a mellow tan. You know, how can I express…”

“Then?” I prodded him to continue.

“She was very fond of me. She would always give me things to eat—things meant especially for her. When she gave her uncle’s children a little pocket change, she gave me some too, and then I took the kids’ money when she wasn’t looking. Sometimes she would even give me a rupee.”

I didn’t mind that this seemed less true factually than emotionally, and so I gestured to Saud not to interrupt.

“She was always finding ways to come see me and was always giving me looks. She asked about my mother. If I had brothers or sisters. Whether I was a wrestler. She would ask me to arm-wrestle. She was very shy. When her uncle was in the room, she made sure to go in and out as fast as possible. We were so close that she would flirt by hitting me and then running away. One day she told me that she liked the fruit of the wood-apple, and so although it was real hot and in the middle of the day I took off across the Jamuna where I knew there were some wood-apple trees. I didn’t let myself catch my breath until she had four big fruit in her hands.

“But there was one thing about her I never approved of. Just to hear a Muslim name made her hot under the collar, and she would curse them out like no tomorrow. Sikhs eat meat too, but she would never touch it. She’d say that since Muslims ate oxen and water buffalo as big as elephants, they weren’t far from being cannibals. And what she said was kind of true.”

His voice trailed off. What Nirmala had said didn’t make much sense, and yet

Babaji’s willingness to agree with her made it clear how much he’d liked her.

“As the time came for her to leave, I was distraught. I don’t know how she found out about my feelings, but she did and started telling me how life wouldn’t be the same without me. Somehow she got her parents to take me along, convincing the mistress of the house, too. Hearing that I was going to leave, my mother cried non-stop and acted like her life was over. My father didn’t know what to say. But I wasn’t going to listen to anyone.

“We left. Nirmala’s parents had a big estate. Big fields. A house in the middle of the fields. They had servants everywhere, but because of her I was treated like one of the family. Right after I got there, they gave me the everyday job of milking the buffalo. One day I was in the pen milking. I’d stumbled outside in the same clothes I’d slept in, and after feeding all the animals, I bent down to do the milking. I don’t know when she showed up. I was still in my underwear. When I saw her, my face turned red with shame. She had been staring at me! Once I saw her, guess what she said? She told me I should get married. Then she ran her hands over my upper arms, ‘Look how muscular you are!’ She put her hands on my face, ‘And look how thick your beard is!’ Then she ran off smiling and I couldn’t move. I was on fire. My hands were glued to the buffalo’s udders. Then finally I broke free from her spell.”

He was breathing heavily and his voice quavered. Then he got lost in his memories. “Wow! You must have gotten some, right?” Saud asked, bringing him back to the here and now.

“Saud! I’d been fond of her, but her words gave rise to a new desire. I thought about her all the time. I dreamt of her. When I woke, the first thing I thought of was her face. I began to lose interest in my work. All she had to do was ask, and I would have tried to move the sky for her.”

It had grown quite late. The shop-owner was waiting on us to leave before he closed down. “Babaji, why don’t you take your story home and finish it there?” the man finally had to ask.

After that how did the story end? Partition was announced. Nirmala’s family fled with Babaji, but they got separated along the way. They never met again. When Babaji got home, he found out that his father had been murdered: against the strict wishes of his mother, he had set off for the Sikh’s house in order to find out what had happened to his son but never returned. Then Babaji married to please his mother. He had two kids. But he couldn’t share his memories with his new family. He did menial jobs to support them and ended up getting a job at a bakery. He had a family but he was barely there. Once his children grew up and went into business, he could finally do as he pleased. He left everything and lived alone. Life was a burden. No happiness, no sadness. Without Nirmala, what mattered?

Before going to sleep, I asked him, “Babaji, you still haven’t told us why you don’t eat.”

“After she left, what could I eat?” he started. “There’s the type of food that’s good for your mind and the type that’s good for your body. I ate as long as it was important to stay strong. But after that? My kids are grown. They’re in business. They have their families now. My mind was all for her. Without her, nothing mattered. Why should I eat? For whom?”

Saud asked the last question before going to sleep, “Was there any hanky-panky or was it pure, what you two had?”

At first Babaji didn’t answer but after a little while he laughed a little dry laugh. “I get what you mean,” he said. “If I’d wanted to, I could’ve. There were a thousand chances. But I was too scared she’d find out I was Muslim. So that was the end of that.” As an afterthought, he added, “The most important thing was that my love was true.”

He fell silent and so did the room. Yet I had the feeling that in that still darkness there were tears streaming down his face.

(Translated from the Hindi by Matt Reeck and Aftab Ahmad.)