Private Faces in Public Spaces: Amitava Kumar

The Art of Anunaya Chaubey

Through my teenage years, I went to school in Patna. The school was called St. Michael’s High School, its buildings dwarfing the small houses around it, the walls of the school going down to the Ganges. Classes were held in English, though that changed later. St. Michael’s was run by Jesuits, a few of whom had come from Ireland or the United States, but several priests were also Indians, from the southern state of Kerala. The artist Anunaya Chaubey was a student there, a year behind me, and I remember knowing him as someone who drew and painted. I am talking now of a time more than thirty years ago.

There is a memory I have of being in school in Patna, and I tell this story in a book of mine, a literary memoir entitled Bombay-London-New York. In the years that preceded my unruly adolescence, I wanted for a short while to be an artist. When we took the ferry up the Ganges to our ancestral village, I studiously observed the scenes I wanted to paint. I remember a stretch of sand and a small red flag on a bamboo pole. Some afternoons, I saw men on the riverbank pulling a boat upstream with the help of a rope. I wanted to paint the shape of tall egrets near the water. I wasn’t very successful. After a painting competition one Saturday, the art teacher told me that he had tried hard to give me the third prize. With a resigned shake of the head, he stopped in midsentence, and I remembered the slim trees and the mountain peaks I had painted for him on far too many occasions.

Anunaya and I shared that teacher—a quiet, decent man named U.K. Singh, whose moustache seemed to droop in melancholic acceptance of the world’s, and perhaps his own, lack of genuine talent. But Mr Singh took delight in Anunaya’s achievement and encouraged him. I cannot guess what Anunaya was learning in those years, but when I think about his past I’m filled with envy. For the truth is that where I saw only the wall, the wall called the future, Anunaya saw faces. He saw the faces inhabiting the spaces that were familiar to us, and he put it all down on paper. It must have required talent, of course, but also purpose, which is more mysterious. I admire this trait very much because in the society where we were born, it wasn’t only that there was poverty—there was a poverty also of ambition. But what Anunaya must have had, even at that young age, is the ability to observe. This is more admirable because those who know how to look are already beginning to understand.

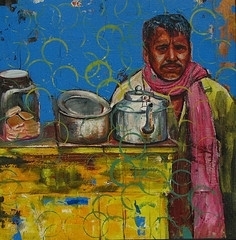

In recent years, a painting of his that I have liked very much is “Day After Day.” It shows a chai-wala, a tea-seller, on the street. It could easily be a sight you would see beside a crowded road in Patna. I like the recognisable aspects of the chai-wala’s face and figure. And the pink gamcchha, like a scarf around his neck. The peeling blue wall behind him, and the brightness of the yellow wooden table that is of course also smirched. More than anything else, the man’s look—his eyes, the hair on his forehead, the set of his mouth—draws me in. I can easily become nostalgic for the spaces of my past, but what brings delight is the fine surprise of the artist’s hand. He has painted ring-marks all over the painting, signs of the endless glasses of tea drunk by the man’s customers. The tea-seller is visible to us only through the tea-stains—just like the raindrops that appear on a camera lens on a rainy day and then become a part of the printed picture.

I like such play on Anunaya’s part because it introduces a disturbance or interference in the visual economy. His skill at representation is so acute that we can be easily tricked by the drama of verisimilitude. The features and expressions on the faces of the people he paints are so “life-like” that one can make the mistake of marvelling at something that is akin to photographic realism. But the real artistic device Anunaya uses, which is also something, interestingly enough, that a photographer relies on, is that of framing. Anunaya’s most provocative paintings are those that crop our view of reality in a way that compels us to see the social space around us, and certainly the painting in front of us, as an area of contestation. The disparate parts of our muddled, even murky, modernity are in conflict on the surface of his canvas; the artist himself is less a warrior in this conflict than an observer, noting with irony the range of emotions, or forces, that are at play in front of his eyes.

A good example of the argument I’m making here is his painting “Amritsar.com.” We are in a gully in Amritsar, locked into the chaos of the street. There are the arresting eyes of those who have turned back to look at the viewer, but there’s also the jam of rickshaws and bicycles and three-wheelers. This is a small town, no doubt about it. And yet, this is no static image. Not only in the sense that there is so much dynamism in the exchange of looks, or in the splash of bright, contrasting colours, but also in the advertizements that plaster the walls. There is a boldly painted sign, with a red arrow, that says “INTERNET.” There are the huge hoardings, featuring cricket stars, for wireless phone. Above the ancient shabby brick-walls of the old town, almost as a part of the soaring blue sky, is the artificial blue of the billboard for Airtel! This is a riot! But it is also just backdrop; what matters are the people in the foreground, the ones who show, to borrow Auden’s phrase, private faces in public places.

“Amritsar.com” can make me nostalgic too, but this is a different kind of nostalgia. It is a nostalgia not for the past, but for the future, where central to the drama of our mixed modernity will be the human figure, looking directly into the eye of history. I give this feeling the name of nostalgia because it appears old-fashioned. In the age of the computer and the World Wide Web, it still finds its truth in the ordinary person walking on the street. It can appear backward-looking, this faith in the individual and his or her experience, but it also belongs to the future, because for too long an arid abstraction as well as technological gimmickry has taken centre-stage in art. Anunaya’s art is a humble but colourful celebration of democracy. It is a vision that is as rich as it is restorative: I reach for it as naturally as one would pick up a glass of cold water on a hot day.

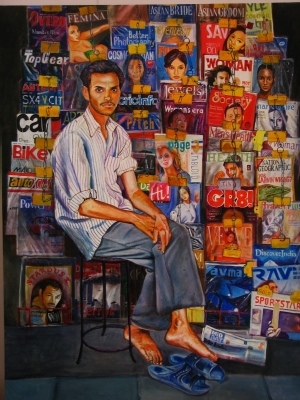

There is another, large painting of Anunaya’s called “Cover Politics” where we see in the display of the glossy magazines the triteness and also the tragedy of our world. Glamorous models, shiny cars, burning towers, film-stars, cricketers, even an alligator—they serve as the backdrop for a man who sits on a narrow stool. He is the magazine-seller. This man is selling glamour, but the soles of his chappals are worn where the big toe should be and the bottoms of his trousers are frayed. The women on the covers of the magazine look out to us, and look past him, and therefore somehow appear hollow. The collection of glitz is striking. The assortment of covers is a collage of our contemporary moment. Asian Bride, National Geographic, Cricinfo, large paper clips from India Today. What has more and more seemed perfect to me is the choice of the seller. His gaze is so direct and the lines of his arms, of his face, even of his shirt, are so simple and striking, that in the world that is all about covers and cover-ups, he simply is. He is the real centre of the painting, and therefore of the world.

Each day, I look at this painting and discover small details. Visitors to my home always ask about this painting that hangs in my home, and I take pleasure in telling them about Anunaya. The magazine-seller in “Cover Politics,” who is more of an enigma to me, looks at us in that level way of his while my friends and I talk and sip our drinks.