Jangarh Kalam: Udayan Vajpeyi

Come over O Bada Dev,

sit in the dense shade of the Saja tree.

Come, create the world,

create it once again.

Where the village comes to an end

keep vigil O Mahrilin Devi.

Let no illness, no disease

head our way,

stop it right there.

At the edge of the forest

stand guard O Ghurri Dev.

Keep us safe,

keep us safe from the wild beast.

At the village crossroads

stay put O Tipthain Dev.

Confer at all given hours

on us a boon of plenty.

Sprawl yourself O Dehri Dev

over our humble doorway.

Let no female demon

step into the house.

Come, make your home

O Chulha Dev

in the freshly smeared chulha.

Fill with the most delicious taste

every speck of food.

When night falls

in desolate streets

make your round O Ratmai Murkhuri.

So the weary humans can sleep,

so they can sleep in peace.

1.

It wasn’t anything new for the residents of Patangarh to leave their village and live and work elsewhere. The father of Prasad Singh Shyam left for Shillong with Verrier Elvin about 40-50 years ago. Elvin went there as an advisor to the government. Prasad’s father was to look after him. He lived there and every month sent a small amount of money to his family. This amount was barely enough to sustain the family which was extremely poor. ‘They were so poor, Saheb, that it’s difficult to describe their condition.’ The family had six brothers and four sisters and no land to speak of. It was a struggle to stretch the day somehow and connect it with the next. The same thing happened with Gendlal, Bhajju’s father. He went to Itanagar in Arunachal Pradesh looking for a job. It was probably at the recommendation of Elvin that he got a job and ended up as an exile at Itanagar in eastern India far away from his village in Dindori tehsil (now a district). He too had to give up Patangarh, and would send a little sum of money to his family. A sum so little that the family lived in great poverty, barely surviving. ‘We used to literally starve. I pray to God to save everyone from such poverty,’ says Gendlal. The shadow of an ancient grief spreads over his face and then disappears swaying on the waves of Mahua.

But the departure of the younger brother of Prasad from this village Patangarh, breaking up under the blow of poverty, turned out to be something special. His departure changed forever the life of Pardhans living in this village. The younger brother of Prasad, Jangarh Singh Shyam! Jangarh’s family, like the family of Gendlal, Bhajju’s father, was (is) a family of Pardhans. Pardhan’s have been the priests, story-tellers and musicians of the Gonds. In a way they have been the carriers of the collective memory of the Gond tribal communities. For centuries. They did not till land or rear animals. Every third year the Pardhans would go to the family of their Gond patron. Every Pardhan family had a number of Gond families as their patrons. They would go there and under the Saja tree evoke Bada Dev by playing their Bana. And then it would be as if Bada Dev had recreated once again for all the listeners this abundant world in the melodious voice of the Pardhans. Bada Dev can be evoked only by a Pardhan, no one else. He keeps sleeping in the Saja tree till a Pardhan comes and wakes him up. Pardhans are the offspring of the youngest of the seven ‘primal-brothers’ of the Gonds. As per the Gond tradition only the Pardhans have the power to awake Bada Dev. They would awake Bada Dev and then sing, too, many other stories. As if they were gifting back to their Gond patron the wealth of his memory every third year. In turn the Gond patron would give to the Pardhan story-singer gold, silver, horses, bullocks and grains. If someone dies in the house of Gond patron, half her jewellery, cooking utensils and clothes would be given to the Pardhan.[1] Having given half the jewellery and utensils to the Pardhan the dead one receives her invisible resting place in an endless story and becomes immortal. From time to time the Pardhan brings under the Saja tree Bada Dev into which the Gonds disappear after they die, just as, as per the Hindu belief, being disappears into the Brahma after passing through the entire spectrum of incarnations. In this belief too, as among the Gonds, the idea of heaven and hell does not figure. Every time Bada Dev awakes, all the dead ones living in him would come down and assemble under the Saja tree. In the awakening of Bada Dev they too would return to their village. For this rich after-life of the dead one all the jewellery, the utensils and the clothes that are given to the Pardhan are still not enough.

The Gond communities always paid the necessary price of keeping alive the collective memory. To an extent they pay this price even today but now this practice is becoming less frequent. They understood the value of collective memory. (They understand it even now.) They would keep it alive not so much to preserve their identity as for keeping the community together. In fact, one should say that they had handed over the task of nourishing the collective memory to a part of themselves so that they could keep together. The threads of the stories which keep the Gonds together were woven by the Pardhan story-tellers every third year. The Pardhans sang their stories only for the families of their patrons. Even now they sing their stories only for them. Many gods and goddesses other than Bada Dev too were (are) evoked. Every third year the Pardhan- singer, at the house of his patron, called (calls) upon a number of gods and goddesses to come and create the world once again. He once again marked (marks) every atom of the world with the touch, the grace of the gods. The fascinated listener experienced (experiences) the throbbing of the divine in the most ordinary processes of life. In a way the story-singing of the Pardhan does what according to Anandavardhan poetry is supposed to do: ‘establishing the extraordinary in the ordinary’. This way for centuries the Pardhan singer has been transforming, for the Gonds, this earth, this very earth full of sorrow and pain, into the land of the gods. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that after every three years the Pardhan went (goes) to the house of his patron and cleaned (cleans) away, with his music and story-singing, the dust of oblivion. So that once again the Gonds can live in the land of the gods flowing in their mind within this world.[2]

2.

The Bana itself, that is the Baja (musical instrument) of the Pardhans, is Bada Dev. Why? It is Bada Dev because unless it produces its sound Bada Dev does not come down the Saja tree. It is inherent in the name Bana that it is in a way the body of Bada Dev, is the garment of Bada Dev. Bada Dev comes down the Saja tree only when it is played. After coming down the Saja tree he possesses one of those present there. If the Bana is not played, Bada Dev will not awake, will not come down the Saja tree, will not possess anyone present there. Bada Dev is because the Bana is. The Gond patron cannot even touch the Bana. The Pardhan keeps it with himself. He alone can touch it. How did the Bana come to the Pardhan? It came to him by the god’s will. There are many stories about this. There were seven Gond brothers. They harvested the rice crop and before husking the crop released a black cock to pick the rice for worshipping the hoe[3]. All the seven brothers anxiously waited but the cock was not willing to pick the rice. Someone suggested that they should look for a person with three names; he only will solve this problem. The eldest brother set out to look for a person with three names. Many days passed. He kept searching without taking any food. Finally he lost all hope and lay himself down under the Saja tree to rest a while. Bada Dev lived in that tree. He came down the tree and asked the eldest Gond brother the reason for his distress. The eldest brother told him about the cock refusing to pick rice and the man with three names. Then Bada Dev said, ‘I’m that person. I’m the one who has three names: Bada Dev, Booda Dev and Mahadev. Go and tell your youngest brother to make a Bana from the wood of the Khirsani tree.’ He also told the eldest brother how the youngest brother should play the Bana. ‘When he plays the Bana, the black cock will pick the rice and you’ll be able to perform your worship. If it happens that way, your youngest brother will always worship me by playing the Bana. He will chant, so he’ll be a chanter, that is a Pardhan.’ The eldest brother came back. He told the youngest brother to make the Bana. The youngest brother made it and played it and the black cock picked the rice. Since then the youngest brother came to be known as Pardhan and he began to play the Bana to please Bada Dev. He gave up working on the land. The remaining six brothers decided among themselves to take care of his daily needs.

It was not without effort that the Pardhan brother learnt to play the Bana. There is a story about how he learnt to play it. He had made the Bana but how to play it? He was thinking about this when he happened to look at the sky. In the infinite blue expanse a Kansgar bird was flying. It would fly straight up and then come down in waves. Then again it would fly up the same way and come down in waves. The younger brother felt that this was the way he should move the bow on the Bana. The moment he moved the bow that way, the Bana began to respond. Drinking Mahua, an old Pardhan is telling me this in village Sanpuri in district Dindori. We are called Par-dhan not because we live on the rice given away by others. This is wrong. Actually we chant, so we are chanters; chanter, that is Pardhan. He has grown old playing the Bana. The melody in his voice is now only a memory. Squatting on the floor he is drinking Mahua in an urban tea-cup. This is the way all Adivasis seem to be in the beginning. Exactly this way: helpless, poor creatures squatting on the ground. And if you have patience and true curiosity about him, he would start telling you about his gods and goddesses. You’ll find that that helpless looking creature has sprouted leaves all over him. Has sprouted leaves, right in front of you! He would keep telling you about his past, about his world peopled with gods and goddesses, about many processes of his life steeped in wonder, and you’ll discover that that helpless, poor creature has become large like the Bargad tree. Now he looks neither helpless, nor poor. Now it is your turn––to look helpless, to look poor, and the shade of that great Bargad tree spreads over you like grace. Sitting near the old Pardhan singer, I’m watching him getting larger and larger. Outside the hut the sun is sharp and hot. I don’t know when some women came and settled themselves in the veranda. In their big, round nose-rings many pieces of the sun are fluttering. And on their faces is a simple, natural tranquillity like sand on the shore of the sea. Nankusiya too came with us. She is Jangarh’s wife and the daughter of this house in Sanpuri. Relatives from the village are trooping in to see the daughter. The old Pardhan singer is one of them. He is a brother of Nankusiya’s mother. Like many Pardhan painters Nankusiya now lives in Bhopal, and it is only once in a while that she visits her mother and father. She is here to see her very old father and mother and her brothers and their wives and their sons and their wives in turn and their little children. We are here with her to know about the creative urges of Jangarh Singh Shyam and other Pardhan painters. It is not easy to persuade the old Pardhan to tell the story of the Bana. He is reluctant. I can understand this reluctance. After all the story of the Bana is sung under the Saja tree, nowhere else. The Bana would be played only at the place where Bada Dev lives. He is hesitating. He is not clearly saying no. How can he do that? We are here with his beloved niece. The niece, that is Nankusiya, grew up with him and is visiting the village after a long time. He is deep in thought, then suddenly he gets up and goes to his place to get the Bana. His getting up takes me aback. He looked like anybody else while he sat with us. Now he is bent double. Nankusiya’s bowed uncle! His body itself looks like the Bana. On the bent back a clean, laundered dhoti, a shirt above and a gamsha on the shoulder. This bowed uncle is the carrier of ancient memories of the Gonds. As if these memories, which are now breaking up, are dispersing and failing, had become a burden upon him and had bent him down. Memories which he has preserved in his singing, kept safe in the stories. These memories can be called the narrativised knowledge of the Gonds. There is no doubt that a knowledge that cannot take the shape of a narrative, which cannot mould itself into a tale, a story, keeps itself beyond the reach of the ordinary people. It does not pass through the countless humanity. The Pardhans have been carrying out the duty of disseminating this very narrativised knowledge in the Gond community. In their stories they begin by showing their own and the Gond’s origin in Bada Dev and then come to the tales which sing of the valour of the Gonds, probably to remind them of their glorious past, to infuse into them the vigour they might have lost. It may not be wrong to remember here that it is said, and on the basis of established evidence, that the Gonds ruled a large part of the central India for 1400 years, which included many parts of Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra. I repeat, 1400 years. Even Bhopal – where, at the end of the twentieth century, that unique style of Adivasi painting was born which pulled us to Patangarh – was a part of Gondwana and Kamlavati was the last Gond queen here. In the bigger lake of Bhopal even today one can see parts of the palace of Kamlavati submerged in water. It was this relatively prosperous Gond society that patronised the Pardhans so that they could refine their music and their style of story-telling without difficulty. One can understand fairly well the role of state or social patronisation in the efflorescence of the arts from the condition of the Pardhans during this period. They had been freed from the necessity of working on the land. They got all their food, jewellery, clothes and utensils from their Gond patrons for whom they sang their stories. It was an arrangement that gave the Pardhans ample time to polish their art. It is this kind of complete faith in and support to the artists and writers which makes a society rich in the arts and literature. If you ask her, a writer or an artist can never prove the significance of her work. It’s in the nature of art that the moment one talks about its purpose, it begin to appear small. The same is true of those who carry the collective memory. They too can survive only if they are supported without condition.

The Pardhans are situated like the court singers and bards. Just as the Pardhans believe themselves to be the brothers of the Gonds, the Charans consider themselves to be equal to the Rajputs. In fact, they go further: they like to think that they are the gurus of the Rajputs. Gurus and priests. At some places Pardhans are called ‘palala’. One can derive its meaning from ‘pala’. ‘Pala’ means ripe. Fruit is placed in ‘pals’ (layers of straw, leaves, etc.) to ripen. As such, ‘pala’ would also mean one who is ripe or mature. In other words, one who is wise, learned. The Pardhans are the wise men of the Gonds. Therefore, like the Charans in the case of the Rajputs, they too used to be the advisors or ministers of the Gonds. In Andhra Pradesh they are called ‘patadi’, which means singers or those who trace the genealogy or the family line, exactly like the Charans. The word ‘charan’ seems to have been derived from ‘uchcharan’ (to utter). Similarly, ‘pardhan’ too seems to have originated from ‘pathari’, that is, one who recites. The Charan utters, the Pardhan recites. In both cases utterance and therefore singing seems to be central.[4] The Charans too would recite for the Rajputs––who were their benefactors––the stories of their valour. Like Pardhans, they too illuminated the valour of the Rajputs. Incidentally, while singing their stories the Charans played a musical instrument called Ravanhattha, as Pardhans played the Bana. Both the Bana and the Ravanhattha are played by using a bow. That is why perhaps both the instruments can closely accompany the linguistic utterance. Both have the ability to underline very clearly the word that has been pronounced.

I have this firm belief that there must have been an arrangement, like the one in the case of Pardhans and Charans, in all parts of India to keep the collective memory in a vital form.[5] In fact, there must have been a veritable network of such arrangements all over the country, which means that quite possibly they were linked with one another. This too must have been an element that connected with one another the various parts of the country. The foundations that, as part of a long tradition, kept our country together despite the attempts made by the British to violently uproot them are yet to be fully discovered. The tradition of story-singing, kept alive by the Pardhans and the Charans, has been the chain that linked each member of each community with the past of that community. At the same time, it has been making him/her realise that s/he is not just the member of a community but also a constituent of an all-pervading entity. These story-songs evoke in the members of the communities the feeling of a citizenship that spreads from their own community right up to the universe. They do not let go of the opportunity to take part in the larger citizenship of the universe because they are the citizens of their own community. The task of adding the dimension of universal citizenship into their communal citizenship was performed by story-singers such as the Pardhans through their beautiful story-singing. It was not for nothing that the story sung by the Pardhan began (begins) with an evocation of Bada Dev and continued (continues) to some great Gond king, such as Hira Singh Kshatri. (It is necessary to remind the reader here that the story-singing of the Pardhans used to be [is] a public affair, and in that singing they [would] recite episodes of the evocation of Bada Dev, Guddi-puja [doll worship] and the valour of the Gonds. However, at home the Pardhan and Gond women [would] tell many other stories, to one another and to children. Travelling through many generations these stories have reached our own times. A Pardhan painter once told me that his grandmother used to tell him stories late into the night. Slowly these stories have begun to appear on the canvases of the Pardhan painters. The worlds of the grandmother and of the grandfather have begun to converge on the Pardhan canvases.)

The old Pardhan singer told me that on the third day of the waxing phase of the moon in the month of Vaishakh, when he wakes up Bada Dev by playing his Bana, Bada Dev comes down and possesses one of the listeners. This is called bhav aana (being possessed by the spirit). It is only because of this possession that Guddi-puja becomes possible. Before Bada Dev awakes, people hide the Guddis here and there. These are packets containing turmeric and rice, tied in a knot. The Guddis bear the names of those who died after the last Guddi-puja. But people can hide other things as well, if they wish. When Bada Dev wakes up and possesses someone, the person so possessed finds out the things that have been hidden. He also finds out every Guddi and every other thing. When he finds the Guddi, the person whose name that Guddi bears merges with the god, Bada Dev, and this merger is Dev Milauni. The merger of the dead man with the great Bada Dev. Though it is true that a person who dies in an accident, his Guddi is not sought by Bada Dev, and he does not merge with him. That unfortunate man keeps dangling between the human world and Bada Dev. Bada Dev digs everything out since he knows each and every place. His all-knowing attribute is not stated here, it is fully realised. What can be a better demonstration of this all-knowing attribute of Bada Dev? Bada Dev is omnipresent (sarvagat); he has already arrived everywhere. This is demonstrated when he digs out every Guddi and every other thing that has been hidden. At the precise spot where a thing has been hidden, Bada Dev is already present, which is why he has no difficulty in looking for anything and finding it. It is the Pardhan only who has been waking up, since centuries, this all-knowing and omnipresent Bada Dev.

3.

Apparently, it is just the crossroad of the village. Three or four pathways originate here. One pathway leads to the elegant though austere huts. One forks off taking the downhill course. One pathway disappears into a field after a point. It’s nothing but the crossroad, but it is here that the village god of prosperity, Tipthain Dev, has his abode.[6] There was no idol there, yet a young Pardhan kept saying that Tipthain Dev is present here. ‘Where is he?’ I kept asking him. He expressed surprise by looking first at me and then at the empty space at the crossing, and kept reiterating, ‘Here, Tipthain Dev is right here.’ After a while the sense of what he said became clear: this is his place and it is in our life-breath that he is consecrated. Tipthain Dev is worshipped on the day preceding Diwali. The village boys and Devar-Devarin[7] make a bamboo chhahur and go to every house in the village; they stretch their aanchal to collect rice and lentils. Devar and Devarin go waking up the saar[8]. All the animals are taken to the riverbank. At the crossing, on ‘Tiptha’, a speckled rooster and a speckled hen are slaughtered. Mahua liquor is offered and prayers made to Tipthain Dev to keep everyone in the village in good health, to keep them flourishing.

There is no dearth of gods and goddesses here: Dulha Dev, Surja Devi, Phulwari Devi, Maswahi Dev, Khairo Mai, Marhi Dev, Mahrilin Devi, Dehri Dev, Dhurri Dev, Chulha Dev, Raatmai Murkhuri, Bagasur…… It’s beyond anyone to keep count of them. The Pardhan waits for some or the other god or goddess at every turning point in his life. Or perhaps at every turning point in his life, one or the other god or goddess stands waiting for him. They inhabit his home, his village, his forest, unseen everywhere. The apparently sparse Pardhan-Gond village is abundantly inhabited by the gods and goddesses. Bada Dev creates the universe. It is in him that everything originates, and into him that everything comes to merge, to rest. Bada Dev is the beginning of creation; he is its end, too. I have heard two different stories about his vehicle. I encounter some difficulty here, but perhaps the Pardhans don’t. At places his vehicle is the horse, for instance here:

The Gonds were seven brothers. They sowed jute in the field. In a few days, the jute began to grow. One day they saw a handsome young man galloping on his horse right through their field. The hooves were trampling the jute saplings. They pounced on the young man with their paitharis. The youngest brother was so scared that his stomach got upset. He went to the nearby ditch to relieve himself. The other six brothers chased the horseman. The field was quite big. At the edge of it was a Saja tree. Seeing the Gond brothers chasing him, the horseman went under the Saja tree and disappeared into it along with his horse. The Gonds saw him vanish into the tree. They instantly understood… This is our Bada Dev who came riding through our field on his white horse. How unfortunate we are that we could not recognise him… Now he is angry with us. He has disappeared into the Saja tree. How do we placate him. Together they began to reflect on this. They erected a platform under the Saja tree. They offered rar lentils. Sacrificed a white rooster. Sprinkled liquor made from Mahua. Folded their hands in prayer. Went on pleading… But Bada Dev was angry. He did not come out of the Saja tree… At this point the youngest brother turned up from the direction of the nullah. He found out what had happened… He said, ‘I’ll find a way. It might please Bada Dev.’… He went and felled a bough from Khirsani tree. He made a one-stringed instrument from the wood and playing on it, began to sing. The notes began to resound in the woods. In the song he began to sing praises of the glory of Bada Dev. Listening to the song Bada Dev was pleased and he made an appearance in the trunk of the Saja tree. He blessed the youngest brother by placing his hand on his head, ‘Whenever you sing my song playing this instrument, I’ll make an appearance. This instrument of yours will be called Bana.’ Bada Dev accepted everybody’s offerings and once again vanished into the Saja tree…[9]

Here Bada Dev rides a horse. But I have seen Bada Dev riding a bull in the other stories told by the Pardhans. I heard the following from Kalavati, a Pardhan artist:

The bull is sacred. In every (Gond-Pardhan) village there is a bull. In fact, every village has its own bull. Bada Dev rides around on the bull. It can enter into any field, nobody stops it. Everyone thinks it is auspicious if it enters their field. Sometimes in the villages the bulls are made to fight each other.

Here it is the bull which is the vehicle of Bada Dev. It is quite possible that in the beginning bull was the vehicle of Bada Dev and later some Gonds-Pardhans turned it into a horse. There seems to be a deep-seated meaning in this change in the vehicles. We can only speculate about it. If we consider the bull as the vehicle of Bada Dev, he comes close to Mahadev. It is possible that the Gonds had accepted some of the adornments carried by Shiva’s representation, or, what is more likely, the appearance of the bull in the ‘eternal representation’ of Shiva has its source in Bada Dev’s bull. In any case, most scholars believe that Shiva is a pre-Vedic god and it is quite likely that he rode the bull right from the beginning, sometimes as Bada Dev, sometimes as an Adivasi god, and that this tradition has come down to this day with the bull as a companion of Bada Dev. If this is what has happened, even so one has to say that although the Gonds brought their chief god close to Shiva (or the so called Hindus brought Shiva close to Bada Dev), yet they did not let him disappear into the image of Shiva (nor did the so called Hindus let Shiva disappear into the image of Bada Dev). That is why the fact that the bull is the vehicle of Bada Dev creates the possibility of a dialogue between the Gonds-Pardhans and the Hindus, but it does not lead to a merger between the two. In this case Bada Dev and Mahadev seem relatively close to each other.

Where to place the horse in the other story? Is it Indra’s horse or the horse of Ashwamedh Yajna or else it is Mahadev’s bull Nandi and Bada Dev’s bull. It is quite possible that the bull-rider Mahadev is what the bull-rider Bada Dev is. It might just be a different way of saying the same thing. (What a difference!) My contention is that this could well be the case. Rather than looking for a continuum between the deities of various communities, the colonial anthropologists, in order to depict India as a fragmented society stated all differences to be inherent, and this is what they were trying their best to propagate. Following their example our own scholars too have fallen into the same groove. Otherwise the most obvious continuities could not have been highlighted as differences. If these differences had not been highlighted to this extent, they could not but notice that the bull-riding Bada Dev could be seen in the same way as the bull-riding Mahadev. It is possible that the horse entered the story of Bada Dev after the British came to India. Once the British rule was established in India, the British-Indian police––which was actually the British-Indian military itself––made use of horses. They were the ones who represented the British rule that had penetrated into the entire countryside. In this sense the horses were a symbol of the new power that was now established in India. The vehicles of the new power. For the Gonds, there could not have been a power greater than Bada Dev. That is why perhaps the vehicle of Bada Dev turned into a horse in at least some stories. Or, it is quite possible that both these vehicles of Bada Dev were independent of our conjecture about them. Whatever might have happened, one thing is clear from this example: the imagination of the Gonds––in fact, the imagination of the Adivasis––is a living imagination. It is not an imagination that has got stuck in a period. At the same time, however, this imagination is not without a basis; its roots go very deep into the Gond (or the Adivasi) mind. There are elements that bind it, that circumscribe it, but it is not perhaps possible to talk about them independently of the others. Even so, this imagination does not hesitate to include into itself the processes that are alive around it. Also, it does not let go of the opportunity to do so. That is why, perhaps, when we asked Gendlal how the Pardhans would safeguard their identity when they move to the cities, he confidently answered that a Pardhan will not give up his traditions and customs wherever he goes, wherever he stays in the world. If he gives up his traditions and customs, then he has given up his religion. Then his religion has come to an end. What is it that is preserved by traditions and customs, or that preserves itself through them, something that does not change with the changing times, as if it lived somewhat above time (like Kaag-Bhushundi in the Puranic imagination) but had the capacity to give space to ever new experiences in its syntax? It has the capacity to expand its ancient syntax while preserving its durability. If this syntax breaks, then, in the language of Bhajju’s father Gendlal, the religion of the Pardhan will come to an end.[10]

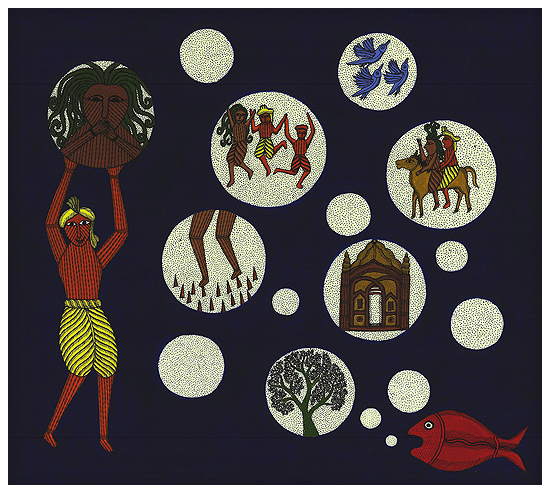

Using a unique style Jangarh Singh Shyam had etched on the expanse of the canvas this very ancient syntax of the Pardhans or its multicoloured harvest. In this syntax also lived the various gods and goddesses of the Pardhans, gods and goddesses who can still be heard in the diverse stories of the Pardhans on the burning soil of Patangarh or Sanpuri.

4.

On the periphery of the Gond-Pardhan village lives Mahrilin Devi. She lives on the boundary mounds of the fields, so is called Mahrilin Devi. She is the goddess who protects the village from visible and invisible calamities. Just like Mahrilin Devi outside the village, Thakur Dev, Gadda Thakrain (Thakurain Dai) and Chaura Khairo Mata protect the village from all around. But sometimes someone subjugates these gods and goddesses who safeguard the village, and when this happens all kinds of calamities like disease, poverty, etc., beset the village. Then it becomes imperative to find out the person who has subjugated Thakur Dev, Thakurain Dai and Khairo Mata. This task is performed by Mahua Devi. The whole village––men and women, old people and children––assemble under the Mahua tree. One of the women is possessed by Mahua Devi. She is called Mahua Devi. Mahua Devi turns eleven boys and a similar number of girls into ‘baruas’ (those who will carry out her wishes). She bids them to find out and bring to her the person who has captured the guardian deities of the village for selfish ends. One of these eleven children or child baruas go to fetch that selfish person. He could be from their own village, or from another village. Wherever he is from, he is brought and made to stand before Mahua Devi. Mahua Devi, then, frees all the guardian deities from captivity and installs them once again on the periphery of the village and the path to peace and prosperity opens up again.[11] On the boundary of the forest it is Ghurri Dev who stands guard. The entire forest belongs to him and so it is he who keeps an eye on it. The Gonds make offerings of wood, stone or whatever else to inform him of their arrival, they worship him, and only then do they enter the jungle. With the grace of Ghurri Dev, they consider themselves safe from the wild animals and find themselves fearless in the expanse of the wilderness. If they find game in the forest, then it is necessary for them to first make an offering to Masvahi Devi, and if they happen to catch fish, it is a must to make Masvahi Devi partake of it before they themselves begin to eat. Masvahi Devi is only concerned with meat-eating. Mahrilin Devi is stationed on the periphery of the village, Ghurri Dev on that of the forest, and in the same way there is yet another deity to protect the village from outsiders. When I kept asking Chattrapal Singh about the Gond deities, almost mentioning yet another goddess, he seemed to be refraining from mentioning her. All he said was that there is yet another deity who says, ‘Now leave this place.’ To whoever has come from outside she says, ‘Don’t stay, move on from here.’ Chattrapal Singh is regarded as Jangarh’s guru. [‘He came to me for only for three or four days, and that was enough for him to learn what he had to, and then he kept scaling heights.’]. He makes sculptures in clay hounded by poverty. He remembers Jangarh very fondly. After all, which goddess is he so reluctant to name? I began to brood over it. In Patangarh the sun was beginning to go down behind the hills but gusts of hot wind went brushing against the skin. The residue of the evening sun came and sat on top of the head like a hot cap. Wherever he took a pause in his speech, I gently brought up my question. At long last he stared at me and said somewhat dryly, ‘Marahi Devi, she kills, if the outsider does not make an escape.’ To this day I haven’t forgotten the sharp edge that arose in his eye while he uttered those two sentences about Marahi Devi. Marahi Devi who chastises anyone who forces his way into the village. To protect their ‘devastated province’ somehow the Gond deities still keep vigil around the village. They may not have been able to protect it against devastation, but their presence is a source of deep assurance for the Gond-Pardhans. Is it the same goddess whose consort Maraha Dev was portrayed by Jangarh years ago?

Dehri Dev is seated right at the threshold of the house. When the house is being built, and the doorway is fixed, it is then that Dehri Dev is installed. Inhabiting the threshold, he remains at the doorstep of the house. Like the transparent glory of godhead between inside and outside. Not separating the home from the outside world, as much as bringing them together. The outside enters the house under Dehri Dev’s gaze. Guests are let in while male and female demons, ghosts and spirits are sent back from the doorstep. Dehri Dev does not let shadowy ghosts cross the threshold. Light can enter the house, also darkness, air, scent, guests, memories, desires and who knows what all. But the she-demons stalking the open forest tracts, fields, and lurking in trees are not permitted to enter the house. Sitting at the threshold Dehri Dev singles them out and forbids them to enter. Having heard this, as I emerged from Nankusiya’s parents’ house, I happened to notice the new door: the invisible Dehri Dev billowed like a breeze in the doorway.

In the nicely dung-smeared corner of the kitchen, and in the equally nicely smeared earthen chulha, Chulha Dev sits keeping his eye on the bride. She smears the chulha first of all, then lights firewood, puts rice on the fire and cooks dal (if in stock), or else kodon-kutki, the millets. After she finishes cooking, she offers some cooked grains to Chulha Dev who is present in the chulha and it is only then that she serves food to others. If this order is disrupted or if this order is disrupted at a particular place, Chulha Dev, by whose grace taste enters food cooked in the house, becomes angry. If in the process of cooking, the bride (or whoever is cooking) becomes apprehensive, and she tastes the food, then Chulha Dev either turns crooked the hand that takes the food to the tongue, or else disfigures the mouth that had the temerity to taste food before making an offering to Chulha Dev. Cooked food should reach members of the household or the guests. The one who has imbued the food with taste, he should be the first to taste it before others partake of it. It means that whoever eats in a Pardhan or in another Gond household eats food that has been approved of by divinity. That is why the Chulha Dev installed by the Pardhan sculptor Gangaram has a crooked mouth: Chulha Dev exhibits his power in this wooden sculpture. If he is angry, the bride or whoever cooks the food is in deep trouble!

In the veranda a child is asleep in the cradle. The entire household is watchful but at the same time is fully assured that the goddess keeps an eye over the child. Cradle-goddess. Goddess of the swing. Jhulan Devi.

Night has fallen in the Pardhan village. People have left for home. The streets are deserted. At every step darkness is strewn like sand. The susurration of the Peepal leaves blending with the humming of the crickets creates an uncanny silence.

In this silence fear is busy assuming different shapes, but the people sleeping in the house are unafraid. They trust Ratmai Murkhuri completely. When night falls she ventures into the village, combs all the streets, passes by each door, and protects the Gond-Pardhans in sleep, this Ratmai Murkhuri. There is no telling what form she will assume. She will turn into a little girl sometimes, an elderly person, a cat, or a cow. Assuming different forms she protects the village from demons of the night. ‘What happens to her during the day?’ I asked the Pardhan adolescent Pradeep. At first he kept looking at me, then he fell silent. A smile came from somewhere and slowly spread over his face. Like fine sand.

5.

Pardhan-Gonds, Agaria, Baiga, Devar, Panaka, etc., these adivasi communities have been deeply interlinked for hundreds of years. Their community occupations have been different but complementary to one another. In accordance with their professions, their self-images too have been different. Different but in deep dialogue with one another. For instance the Gonds primarily worked their lands and were skilful rulers (which is why they ruled over central India for hundreds of years. What could have been the finer details of this long-lasting ruling system, needs to be investigated. It requires deep insight and discrimination to rule over a kingdom so competently). The Pardhans were their chief advisers and singers. The Agarias were the iron-makers of the same region. From Maikal ranges, they produced iron in their tiny kilns and made it available to ironsmiths who turned it into tools for agriculture and hunting. The Devars have been keepers of pigs and at the same time Ahirs of some sort. The Baigas, apart from raising crops, had a deep knowledge of herbs, and that is why they were looked upon as local healers. In other words the adivasi communities inhabiting the huge contiguous territory of Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and Orissa have been practitioners of various skills for hundreds of years. The areas of their skills have been diverse but mutually complementary. It is this very diversity which might have formed the basis for their varied self-images. A map could well surface if we placed together these complementary skills of adivasi communities. This map will be incomplete, quite incomplete, and there is no room here to piece it together, but if were in a position to do so, we will see that the communities called adivasi and thereby regarded as less developed, less orderly, had organised themselves in a very developed way, and that organisation, compared with that of modern society, was far more egalitarian, more open, and had the possibility of nurturing the self-respect of each member of the community. Perhaps in the flow of authority in that community arrangement, all members found a place. That is why they did not have to devise prisons or mental asylums in order to protect centres of authority. When that social organisation weakened and broke down and shattered is up to those scholars to investigate who are worried about the future of India. But here we will try to find out how the adivasi or more specifically the Pardhan community is trying to regain that broken and shattered world. In that attempt a way to understand their art of painting might open up.

In the diminishing of the glory of the Gonds and their sibling communities, it was the Mughals, the Marathas and most of all the British and the administration of independent India that played a role. The social systems that the British destroyed in order to replace them with their own institutions weakened the intricate weave of the adivasi India at some places, and shattered it completely at others. In the lure of modernity the rulers of independent India continued with those institutions. Is it not, then, an encroachment on the adivasi way of life, first by the British and then by the new rulers? This situation had already begun to deteriorate in the beginning of the nineteenth century. By 1930 things were messed up to an extent that the adivasis came to regard paradise as a stretch of forest land that had no guard, and hell as a long wild stretch without a single Mahua tree.[12] As the position of the Gonds weakened, the patronage of the Pardhans too began to fade away. In this state of affairs at places the Pardhans entered into arguments with Gond rulers as they were too subservient to the Mughals and the Pardhans were opposed to this attitude of theirs. And why not? How could the Pardhans bear to see that the valour of the Gonds, the cherished subject of their song and narration for hundreds of years, had now given way to ingratiating postures and salutations? And yet, even in the somewhat shaken up form, the kinship between the Gonds and the Pardhans remained intact for a long period of time. It might be more appropriate to say that this kinship lost its practical aspect that earlier prompted the Gonds to offer shelter to the Pardhans. Now this kinship sustained itself at a formal level. To this day, many Pardhans turn up at their Gond patron households for singing their stories. But now there is hardly a Pardhan family that is offered patronage by a Gond patron. That is why Gendlal Pardhan says, ‘Now the Gonds hardly have anything themselves, so how can they look after us?’ The destitution of the Gonds in turn thinned out the bardic practice of the Pardhans. Various historical factors ripped that texture apart in which the complementary existence not only of the Pardhans but of all adivasi communities could have stayed intact. After attaining independence, we neither understood that complementarity nor tried to rearrange it. The understanding with which we went about making new systems did not rest in the least on the time-old and authentic community systems prevalent in the country. On attaining independence what we had to do was to open up the empowerment channels of our community life blocked up by the British. What we did instead was that we tried to fit the multilayered community systems that had evolved with such subtlety and care into the model of modern development, and it was a gigantic but futile enterprise that rendered practically all communities destitute and helpless. With the loss of patronage, the Pardhans had to turn to agriculture. As most of them were extremely poor, and did not own any land, they were forced into agricultural labour. Now their stories, their singing, their Bana could no longer sustain them. That is why the Bana became less of an instrument to play, and more of an object of worship. The tradition of patronage might have remained in practice to some little extent, but it was hardly enough to keep alive the fire in the Pardhan kitchens. The Pardhans are having to let go of their Bana. In its place now there is the ploughshare, the ox, hoe, spade, or metallic vessels. There is no practical significance of story-singing any more. But mythical self-images are made in hundreds of years, and are hard to change. Because even though the customs and ritualistic practices may not be directly linked to self-images, the shadows of mythical self-images keep drizzling into them, something that continues to this day. That is why these shared community self-images keep throbbing like raw nerves in each and every member, even though their practical moorings have been lost. The Pardhans may not be the bards any more, but their mythical self-image has been of being precisely that. Under the Saja tree the visual of singing for the Gond patrons still lingers in their eyes. As if their entire world had arisen from the surface of the earth, and had slipped into the depths of their dream. It was with these dreams that Jangarh Singh Shyam left Patangarh for Bhopal twenty-three years ago.

6.

Jagdish Swaminathan, the great painter and thinker of the twentieth century, was of the opinion that it wasn’t only the urban art that qualified as art, as the British would have liked us to believe. The tradition of folk and adivasi paintings all over the Indian countryside is just as important. This too is contemporary art. The adivasis are neither the denizens of a backward world, nor are their works the creations of some bygone age. These works belong to the present age. It is a mistake to look at mankind and art with a European historical perspective. Neither man nor his varied artistic creations can be understood in this way. It was in this quest to understand that he sent several teams of young painters to various regions in Madhya Pradesh urging them to collect paintings, sculptures, or visual art of any kind for the newly established multi-art set up of Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal. This was a unique enterprise to rid ourselves of the mental shackles the British had left behind for us.

Vivek was the leader of the team touring Mandla. This team went about this region to collect works of visual art. During this trip they also visited this village called Patangarh, close to Garha Sarai, on the road that led from Dindori tehsil to Amarkantak. It was here, in this village, that the British anthropologist Verrier Elwin stayed from the fourth decade of the last century to the sixth. That might have been the reason for the name this village has acquired for outsiders. It was perhaps at the advice of the wife of Elwin’s fellow worker Shyam Hivale that Swaminathan sent Vivek especially to Patangarh. He might have had some idea that someone in that village used to make clay sculptures. That was the case, as Chattrapal Singh lived in Patangarh even in those days and he did make sculptures in clay. Vivek did not find a single painting on any wall, nor a single clay sculpture anywhere in Patangarh, a village that sprawled over three or four hills. He was about to leave in disappointment. It was evening. The trees in the street cast long shadows on the ground. All at once Vivek happened to glimpse something: in the dappled sunlight filtering through the shadows of those trees a few yellow lines lit up. In those lines, a figure seemed to be emerging. An extraordinary yellow Hanuman carrying the Sanjivani mountain on the palm of his hand was seen shimmering on a wall. Vivek was instantly struck by that picture. When he made inquiries, he found out that the painting had been made by a boy whose name was Jangarh Singh Shyam. ‘He used to work a lot, Saheb.’ Jangarh’s uncle, his father’s younger brother, was pointing this out to me years after this incident. ‘ He did odd jobs as a labourer sometimes, lugging dug-out soil, he did whatever he was asked to, always, never said no. Those were the days of extreme poverty, Saheb.’ Jangarh’s elder brother says, ‘He took the cattle out grazing everyday to the riverbank. And would take his flute along.’ And why not? Jangarh was a Pardhan after all. Sometimes, taking all the village cattle, a few friends would go to the river for an entire day. They let the animals graze, they bathed in the river, tossed about in sand. Jangarh would sit playing on his flute all by himself. The elder brother went on to tell me that on certain occasions, after he had had his rolling spree, Jangarh would marvel at the impressions of his own body printed in sand. ‘He would try to complete the picture.’ ‘Complete?’ ‘Yes, parts of the body that did not leave clear enough impressions, he tried to draw with his finger. Then he would show it to me and ask me for an opinion.’ Arjun, Jangarh’s friend from those days, said to me, ‘Then he started painting on the wall. Even then he used to ask me what I thought of it.’ When he was just beginning to take his pictures from the sand to the wall, Vivek happened to meet him. Jangarh was the only such painter in the village. Not a painter, perhaps, but a ‘potential’ painter he surely was. In those days, apart from him, none of the other Pardhans painted. And why should they have painted? They were musicians after all, even though their music had slipped into silence for lack of patronage. That social texture in which the Pardhan instrument Bana could be heard, wherein their song found a resonance, had come apart now. The music, the song, the narrative they used to create under the Saja tree, runs in their blood to this day. Overflowing with these narratives strung in the music that is hundreds of years old, Jangarh Singh Shyam accompanied Vivek to Bhopal. ‘First we stopped at Dindori, where we gave him some paper and colours and asked him to make something. Amazed, he went on looking at the colours. He touched them the way you touch clay.’ Having left Patangarh, Jangarh now came to Bhopal. The boy who belonged to a family of bardic-singers had now landed in a world of colours.

7.

Various art forms despite being autonomous entities are, in fact, not autonomous. In every art form the presence of another form is reflected. There is a beautiful story in Vishnudharmotar Puran about this. King Vajra wishes to build a temple and install an idol in it. He asks the sage Markandeya, ‘O wise one, enlighten me as to how I should install an image in the temple?’ In reply to this question, with what Markandeya says, a series of questions and answers starts off, but whether there’s an end to this series or not, we find that in our own context of various art forms, the very nature of art itself seems to be revealed in the process. It is hardly likely that in the context of the arts, a similar attempt to understand the very nature of art itself has been made elsewhere. When King Vajra inquires about the way an idol should be installed, that is, about the art of making idols, Markandeya answers, ‘O King, the man who does not understand painting cannot grasp the characteristics of idol-making.’ ‘O wise one, if an understanding of painting is required to grasp the characteristics of a divine idol, then explain to me the art of painting,’ says the King. ‘Without understanding the art of dancing, it is not possible to understand painting, as, O King, dance and painting are both an imitation of the world.’ The King says, ‘If it is only with the knowledge of dance form that a man can grasp the art of painting, then teach me the art of dancing first and only then enlighten me about painting.’ Markandeya says, ‘The one who does not understand the music of instruments will find it very difficult to grasp the art of dancing, because without this music, dance is not possible.’ The King goes on to say, ‘O holy one, if the music of instruments be the prerequisite for understanding dance, then be kind enough to teach me this music, and only then illumine the art of dancing for me.’ Markandeya responds by saying, ‘O infallible one! Without song you cannot understand music. The one who has grasped the art of singing, is properly initiated into the understanding of all things.’ And then Markandeya, with a view to expound the art of song, goes on to shed light on language and poetics, and in the light of poetics, the theatrical forms, and in that order, on song, music, painting and sculpture.

Perhaps this is what this story conveys: an art form is subtly present in another one. It is also being said here that within one art form, the creation of another is forever possible. As if in every art, every other art remains present, layer upon layer, and if we look close enough we could savour one in the other. As if every artist engaged in his pursuit, unknowingly keeps bringing other art forms into play.

8.

When Jangarh Singh Shyam came to Bhopal, this is exactly what happened with him. We have seen how the Pardhans have been bardic singers for hundreds of years. We have also seen that this practice continued to wane with the weakening of the Gond kings, and with the process of impoverishment of the Gond tribe. But their art somehow remained alive within them in some way. Perhaps it went into a hibernation of sorts and began to wait for an opportune moment for blossoming all over again. While this waiting was going on, Jangarh became acquainted with the art of painting, and his dormant creativity began to assume a new form. Now it turned in the direction of another artistic expression. This was a strange transformation. The time-old creative urge was shaping up into something new. And this something new was painting. Having begun with filling out his own figure in sand, he moved on to paint the walls in the countryside of Patangarh, and the moment he found the conditions conducive to his art, a wonderful school of art came into existence. This was a unique occasion for the transformation of the Pardhan musical tradition into the art of painting. And the birth pangs of this were borne with utmost sincerity by this country-boy from Patangarh. In other words, when the bardic tradition of the Pardhans either lost the means to express itself through musical notes, or else got fewer occasions to do so, it chose to express itself through colours and visual forms. Jangarh is the first milestone on this path of transition. It was he who now began to portray the Gond deities, the plants and trees, the rivers and springs along with the Bana, in the absence of song. He now began to outline on paper and canvas that entire world which was being sung in the Pardhan tradition for hundreds of years.

The Pardhan musician began to nurture his tradition in painting, and not much time has elapsed since the occurrence of this unique event. It was only twenty-five years ago that it took place. It won’t be an exaggeration to say that this school of art initiated by Jangarh is nothing but painted narrative song. Now the deities were waking up in colour, throbbing in lines, and went peering through dots. The stories, instead of finding expression through song, were manifesting themselves now on canvas. In the Pardhan psyche, musical notes have begun to impart their mystery to colours and forms. This wonderful event of the transformation of one art into another, was something that was taking place right in front of us, and which we have already glimpsed in Vishnudharmotar Puran.

9.

No sooner did Jangarh Singh Shyam pave a way for his own creative expression in the realm of painting, than a whole bunch of Pardhans started off in that direction.[13] For years many of these Pardhans came and stayed with Jangarh, assisted him in his work, and learnt how to paint. Many young Pardhans who came and stayed with this young man in his early twenties watched out for the possibilities of a new world in utmost wonder. Jangarh and his wife Nankusiya devoted themselves completely to strengthening this new way that the Pardhans had found for themselves. As far as I know, in Jangarh’s house food used to be prepared for a lot of people, and arrangements made to put them up somewhere. It was less of a household and more of a labour room where the Pardhan tradition was perpetually in the process of being born. The Pardhan music was now transforming itself deep inside them into the art of painting. Jangarh had proposed a new way of keeping up the waning creative tradition of his community and letting the heritage of music remain intact. The music, instead of being created from the Bana, accompanied by the singing of the Pardhans, now began to configure on canvas. It is amazing that this event of the transformation of an art form did not occur in a Pardhan-Gond village, but in the city of Bhopal. In the light of Jagdish Swaminathan’s deep insight, in the cool shade of his compassion. The city of Bhopal should take pride in the fact that it became the birthplace of a unique school of art. A school of art that was initiated by a Pardhan whose name is Jangarh Singh Shyam and which is flourishing at present in the hands of a number of his fellow Pardhans, in Bhopal.

What should this school be called? ‘Jangarh Kalam’, as the painter Akhilesh puts it, or else ‘Pardhan Kalam.’ ‘Jangarh Kalam’ or ‘Pardhan Kalam’ or ‘Jangarh Pardhan Kalam.’ The Pardhan painters themselves may not feel any need to name this school. But now that they have to make this art form survive in cities, a name might come in handy. It could well turn out to bind them in a mould. Who can tell? The fact that this school was shaped into existence in the heart of a city proves that with appropriate support the adivasi art could flourish just anywhere. Jangarh and the young Pardhan men and women who followed him from the villages like Patangarh, Gaar Ka Matta or Sanpuri, began to paint prolifically as soon as they found an opportunity to do so. As if the music that has been flowing deep within them somewhat timidly for the last few centuries had now found a congenial new ground. Innumerable deities, plants, birds and animals, rites, and festivities now rushed in the direction of the canvas to find a niche for themselves. First it was only the Pardhan men who practised their art, now the Pardhan women too became intensely devoted to painting. The story-singing and the Pardhan customs and conventions now vibrated in colours and forms. The collective memory was being borne by painting in the place of music. This is mostly an endeavour on the part of the Pardhans to save their shared memory. In a way it is the portrayal of the narrative of ‘Jangarh Kalam’ and of the grief of not being able to sing their narratives anymore. At the same time as it is a new form of the narrative, it is a song to grieve the old form, music. It is a remembrance of home, and a grieving over its loss. The next stage of ‘Jangarh Kalam’ is sculpture. Which means that some Pardhans are now beginning to turn to sculpture under the influence of the paintings of this school. Some of these artists are now giving form to their narratives through sculpture.[14] Gangaram stands way out.[15] His sculpted deities, his birds and animals, and his heroes and heroines, as if, come to a moment of repose from the flowing current of the narratives. Their postures seem to have a flow that suggests their next move. Whether it is Gangaram, Ramkumar or Sukhnandi, they sculpt a fragment of flowing time in a piece of wood. Unlike what happens in the tradition of sculpture in European Renaissance, they give form to the flow of time rather than capturing it in still form. This is what the paintings of Jangarh Kalam are like too. If there are flying snakes, what lurks somewhere in the picture is the belief that whoever happens to fall under the shadow of this hundred year old snake will be struck by paralysis. The cause and effect of paralysis are both flowing in the painting itself. That is why in Jangarh’s paintings, and in the paintings of other Pardhan artists, wherever there happen to be flying snakes, the atmosphere seems to be somewhat intimidated as if it had been paralysed. The cause (the hundred year old snake), and effect (paralysis), are both present at the same time flowing into each other. When the snake that is Time grows old, it paralyses living things. Is it perhaps a glimpse of an aeon coming to an end that surfaces on Jangarh’s canvas in these pictures of flying snakes?

10.

Many artists of Jangarh Kalam are now held in high prestige. They are constantly invited to various places for work. In many of these places they are treated rather shabbily. In particular it is in administrative set ups that this happens in a most disgraceful manner. Since these artists happen to be adivasis, they are having to suffer this treatment even more acutely. But even so the prestige the Pardhan artists enjoy is now fairly widespread. Two decades ago in the famous Pompideau Centre in Paris, in an exhibition entitled ‘A Hundred Magicians of the World’, Jangarh Singh Shyam’s work was exhibited with an honour befitting his work. Apart from private collections, his works and those of his fellow artists working in the same tradition are now found in art collections of various galleries both home and abroad. The Pardhans have now found a new outlet for their creative expression. Either in their own villages, or else making it to cities they are giving form to it in a variety of ways. It is also a source of livelihood for them. Exactly in the same way as it is, say, for Hussain or Sayed Haider Raza. The only difference being that many modern painters, despite churning out merely designs, are treated with great respect, whereas the Pardhan painters are still to get there. But it is not their art that is to blame for this; it is their status as the common people of India. But despite this state of affairs the best artists of ‘Jangarh Kalam’ continue to paint. Some have fallen prey to repetition. Some of them have adopted this style not to create but to earn a living for themselves. And there is nothing strange in this. This phenomenon takes place in every school of painting. After all, every bard of the Pardhan tradition did not happen to be a great singer. He happened to save the collective memory of the Gonds sometimes with great beauty and at other times with less beauty. The paintings of ‘Jangarh Kalam’ are doing precisely that. The problem is that modern art in Europe, instead of awakening collective memory, seems to be narrating the loss of it. It is a narrative of this loss. A document of how the community fell apart and human beings were reduced to individual persons. It is not as if these artists did not attempt to awaken collective memory, but then their art was doomed to fail in this attempt. The community could not be saved. The substance of collective memory got so scattered that it became almost impossible to string it together. As a consequence, the basic function of painting, or, for that matter, of art per se was no longer the sharing of a collective experience (memory, for instance); it became instead a display of the superiority of artistic skill. It is not as if in the art produced in the communities rich in collective memory, artistic skill does not enjoy prestige. Of course it is valued, but mere artistic skill is not the only basis for evaluating art. Art at the same time as it gives voice to the artist’s own soul, also tries to tell everyone’s story and this attempt of art is perpetually defeated in the broken, fragmented social order of modern Europe. Though it is true that a few artists portraying their personal experience manage to form a community of fellow-feelers, but an appreciative community that is attuned to empathise with the work of an individual artist does not last long. That is why in order to survive, art turns to newspapers, to critics and journalists instead of engaging a truly responsive audience. In this scenario, art, instead of awakening a personal or collective experience, devotes itself to the shallow business of luring these heartless people. Art no longer remains a process, but becomes an object. All this was not required in the Indian context, as despite the havoc wreaked by the British ours was still a relatively cohesive social order. A lot of our collective memory was still quite intact. But our own modern art went some distance the same way, quite willingly, whereas Western art could not help doing so. There are exceptions, of course. Jagdish Swaminathan, for instance. But they are so few and far between that they fail to address nothing but a sense of deep loss.

We will have to wait here a moment to ask ourselves if there is no such art that penetrates through social differences and attains to a universality? Which scissors through the layers of its own culture and civilisation and succeeds in touching a truly responsive person with an aesthetic experience? Which tears right through a member of any culture or civilisation the way a child’s crying would? Sure there is, but it is not from the periphery of its culture and civilisation that such art comes into being, but from the very core of its heart, from its most sensitive zones. It can’t be born out of an indifference to it. Such art resists turning into an object, remains in a never-ending process, awakens collective memory on the one hand, and rejuvenates its own wellsprings on the other. Awakening the collective memory it reaches a place which could be inhabited not by a member of the community that engenders it, but by a member of any community. Rather it happens to transform a sensitive member of its own community into a world citizen. When it comes to painting, modern knowledge is not so much interested in artistic experience as it is in the art object per se; that is why it is constrained to understand a work of art in the context of its elements. The paintings of Jangarh Kalam evoke collective memory in the Gond-Pardhan community at the same time as they can move any sensitive soul anywhere in the world: these works are true to the culture and the time in which they are created. They do not feign the expression of a universal experience; they are simply letting their altogether indigenous experiences manifest themselves through tradition. And that is why, perhaps, they acquire this power to move a sensitive human being anywhere in the world. It is true that we all have a zone in our experience which is located beyond the specificity of culture and civilisation, and which the Indian architect Charles Correa identifies as ‘shunya’.[16] But the power to churn that zone to the depth is found only in the art that has the fragrance of the particularities of a culture or civilisation. In other words, it is only through local dirt-roads that one reaches that ‘zone zero.’

Jangarh Kalam is unique among the modern styles of painting. It is new, yet is hundreds of years old. It is hundreds of years old, and yet it was born merely twenty-five years ago in the city of Bhopal. It does not compare at all with modern schools of painting. Through Jangarh Kalam, the Pardhans are engaged in sheltering their age-old collective memory. It is true that they are also making various experiments within this school. It is also true that our middle class, by imposing its second rate sensibility on these artists, is managing to dislocate their art from its original source of inspiration.[17] And it is true that some of these Pardhans are being forced to turn Jangarh Kalam into a semblance of bad taste. But in the middle of all this they are still, somehow, engaged in preserving the Gond environment, their shared memory, their deities, their heritage of tales and legends. Some of the artists of this school are seen to be making commonplace paintings. If some of them are passing their days in making bad paintings, the root cause of it lies in the patronage offered by urban systems. The Gond patrons never instructed the Pardhans as to how they should awaken Bada Dev, never told them how to sing the stories charged with their collective memory, nor taught them how to play on their Bana. The Pardhans were free to present their art any which way they liked. The Gond patrons have been accepting their creations on their own terms. It was in this way that the bardic practices, and the musical tradition of the Pardhans has remained intact and alive for hundreds of years. But the Pardhans took to painting only in the city. They invented Jangarh Kalam and put it into practice in the city itself. Among the city people. These paintings may not have been addressed to people in the city, but sure enough the buyers of these paintings are these city people. These city people seldom allow an artist to have freedom. For most of them the artist, especially if he happens to be an adivasi artist, is hardly more than a servant. (That is why he is asked such questions: For whom have you made this picture, we don’t understand it, so what use is it?) This servant-artist should make the kind of paintings they want. (The demand made by these customers is communicated to the artists by the art-galleries.) It is not a culture of the spontaneous acceptance of art; it is the culture of making a demand from the artist. If Ganesha is what they want, how can they let the Pardhans make an image of Bada Dev. If plants and trees is what they want, how can they let the Pardhans make Mahrilin Devi in Jangarh Kalam? And since it is precisely these people in the city who wield authority in practically all centres of power, since the British left for their homeland after handing over power to these very people, and since they carried on with the same system that was devised by the British against the common people of this country, the poor Pardhans are forced to make coloured trees and plants, birds and animals and images of Ganesha, instead of painting the narrative of their collective memory.

11.

Jangarh Kalam is an adaptation of the Pardhan music. The transformation of ‘music’ into ‘visual form.’ The peculiarity of Pardhan music is that it has the ‘disturbed equilibrium of musical notes.’ That music, like most adivasi music, assumes form in disturbed equilibrium. It has neither the harmony of Western classical music nor the melody of Khayal (Natya). Like all folk music of Asia it has ‘call,’ invocation. This music, sustaining itself in a disturbed equilibrium, calls out to Bada Dev, its collective memory. It is the endless drifting of a boat that is about to sink. Under the Saja tree in accompaniment of the Bana the Pardhan invokes Bada Dev, then other deities among whom, now, deities like Saraswati are also there—then he sings the stories of Gond valour, or rather he calls out to it. He invokes the deities, so that they too participate in his collective past, so that they should not only lend bounty to the present but should imbue the past with divinity. At the core of this music, the utterance of the word occupies a prestigious place. Perhaps this utterance lies at the very core of every other kind of music. But since it involves a calling out, this utterance has more of an edge. The journey of this voice to utterance and then to music can be seen even here. This is the music of leaving footprints on the vast expanse between speech and song. That is why the Pardhan tries to fully dramatise everything from plain speech to full-throated song. In the paintings of Jangarh Kalam too this phenomenon can be seen. Here too on the canvas every element seems to be bearing the word. Here the very word Bada Dev has been transformed into the image of Bada Dev, the very word Maswahi Devi into an image of Maswahi Devi. At times these words seem to be the parts of an extended story, at other times the frozen fragments of a Pardhan artist. Practically in all these paintings there seems to be a rhythm that assumes form in the disturbed equilibrium of the canvas. These artists, instead of balancing the canvas (the way it is taught in modern painting), try to get to its beauty in the discord of the music. Sometimes a straightforward and simple story seems to be unfolding itself (in the undivided space of the canvas two or three episodes of a story are seen together as in the Pahari miniatures), at times this story seems to manifest itself in a musical form. The path from utterance to song seems to be running through several canvases. There is a fundamental difference here between the traditional miniature painting and these paintings. In all miniatures, whether they are Rajput, Pahari, or Malwi, the straightforward description of the scene is almost missing.

Whatever is seen on paper is, as if, strung on a very natural though intricate rhythm, as if the painted thought has been woven with strands of music. Radha is not an uttered word ‘Radha’ here, it is a sung word ‘Radha’. Miniatures don’t portray tales; they attempt to portray bandishes, the words that are sung. In Jangarh Kalam all words ranging from utterance to song find a place. For instance, in most of Durgabai’s canvases it is words that find beautiful forms; in the paintings made by Jangarh Singh Shyam or Bhajju Singh Shyam there is everything ranging from the uttered word to prayer. In most of Jangarh’s canvases there are forms strung in unique rhythms, as if the songs had just taken the form of pictures. A few paintings of Jangarh Kalam are purely contemplative figures that might have reached the Pardhan canvases through the medium of sculpture. In these canvases perhaps for the first time the Pardhan deities are being sculpted—having inhabited their own names in song, they are in the process of showing their forms for the first time. This is the transfiguration in colour of the divine images that have been inhabiting the very heart of the word. This is the descent of the dreaming world of gods into the wakefulness of the canvas. These gods awaken from the canvas their dream presence. They call out to it.

The Pardhan narratives are collective narratives; all Pardhans and Gonds partake of them, share them. But based on these very narratives the paintings of Jangarh Kalam are individual. They are part of Jangarh Kalam, but if we look close enough we can see their distinct features. It is not because the paintings of this flowing style cannot be imitated; it is because each Pardhan painter looks for a spontaneous way to express the abundance of the Pardhan narrative tradition. Though the subject matter is the same, the artistic experience ensuing from it is not. It is a bit like the Rama and Krishna stories that reside in collective memory, but from Jaidev to Raskhan, from Valmiki to Kamban, they manifest themselves in unique ways. There is little doubt that a few Pardhan artists have fallen prey to repetition while giving form to the Gond-Pardhan narratives, but it could still be maintained that several painters and sculptors among them have given expression to these narratives in altogether distinct ways. (Rather some Pardhans, despite painting in this very style, are no longer confined to the Pardhan ambience. Bhajju Singh Shyam’s London-tales and a few paintings of Durgabai are some instances of this, but these paintings are rendered Pardhan in a way that the London of Bhajju’s paintings seems to be a place contiguous with Patangarh!).

In Jangarh’s paintings and in the painters who came after him, the dot has been used a lot. At times the entire figure is made with dots, and sometimes they are used to change the tonality of colour or to fine tune the colours. Where have these dots come from? I think they have two sources: tattoos and masks. The traditional Gond masks were decorated with dots, and in tattoos the dots are used anyway. Tattoos, as the Gond-Pardhan believes, are the permanent human ornaments, especially women’s, and it is only when they have been checked that a dead person is allowed entry to heaven. The dots have been paving for the Gonds the pathway to heaven, and it is through these dots that the figures and forms are made in a way that a wonderfully light and fleeting quality is achieved in the paintings. This characteristic is especially found in the drawings. It is quite obvious that this evanescence is present in the way in which these paintings are made. Why are these forms or figures so sparse? They are meant perhaps to awaken the world which already inhabits the Pardhan mind. It is not the art of making forms; it is an art of awakening the forms. The forms here are merely signs to awaken the forms that already inhabit the mind. They are not so much ‘forms’ as they are ‘words’.

These paintings are imbued with a deep pagan consciousness. The deities are present not only where they have been depicted. They are also present where the painters have made a tree or a bird or grass, or have painted some Gond-Pardhan ritual. Every enterprise in the Gond-Pardhan life is mediated through some deity or the other. To them the space between nature and man appears as if it is inhabited by gods and goddesses, who connect one to the other. Nature is worthy of worship because dealing with nature you are dealing with gods and goddesses. It is also worthy of worship because several deities inhabit it: Bada Dev lives in the Saja tree, Mahua Devi in the Mahua tree. The deities are worthy of worship because they connect human beings to the unpredictable processes of nature. At every moment, like an inscription on every particle, they surround the human world. Divinity or ‘godhead’ is not an essence that has been extracted from nature, on the contrary it is a live world sprawling between man and nature. At every given moment it is engaged in managing everything ranging from the gift of taste to food to providing shelter to the dead Gond-Pardhan in the Saja tree. It also keeps regulating the Gond-Pardhan life in subtle ways. For instance, if at the time of a Gond-Pardhan wedding Bagaisur chooses to possess somebody, and if he is not propitiated by being offered the blood of a freshly slaughtered pig, he could bite the bride or create some other havoc. So whenever a wedding will take place, Bagaisur will be well looked after. It is through the mediation of Bagaisur that man (bridegroom) is able to establish a living connection with nature (bride).