Forest: Sharmistha Mohanty

This is night where lovers, gods and travelers walk without a lantern.

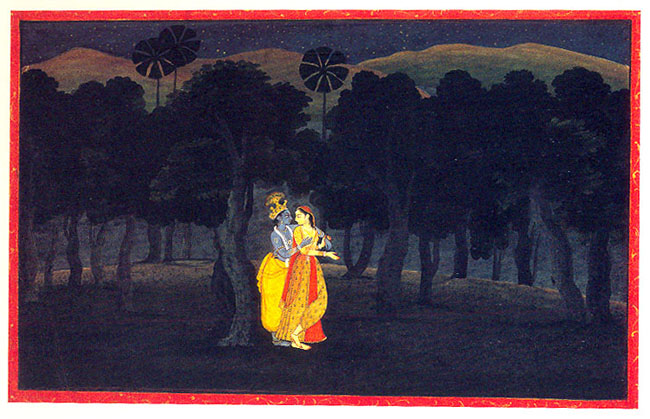

A luminescence separates the clear ground from the tree trunks, the trunks from their leaves, the leaves from the sky. The foreground of the forest is shadowed, but over there, beyond the trees, the land curves in an arc like a horizon, and the luminescence grows into a pale silver light. That is where he wants to go. So he begins to walk, through the dark blue night between the tamal trees, each one of which is curved in a different direction. Next to one tree he sees Radha and Krishna, entranced by each other. Radha’s open palm, angled towards the ground, shows the way home. But her legs are crossed one over the other as she stands, and her right foot rests firmly on the earth, her face turned in exactly the opposite direction to the indicating hand, towards Krishna. The traveler passes them by, but in his eyes there remains an imprint of the way their bodies curve, always outwards, touching the night, and next to them the tamal, leaning away from them. The reticent golden glow that illuminates their bodies from within also lights up the left side of his face and shoulder as he passes by. The traveler can feel the glow on him, but it is towards the pale incandescence beyond that he moves. Already he feels it is something he recognizes.

The traveler is not in search of adventure, the wilderness, endless cities. His travels are impelled by an extreme necessity, the need to save his life, from the inside out. The body has never been in peril, but his life, his life has. If his body were imperiled, his walking feet would feel the scratches of thorns, bleed from the sharp points of rocks, get blistered from the surprises of landscapes. But what he feels instead are the textures of moss, mud, seashore, pebbles, sand, grass, puddles, flowing water, he loves them all, and he pays attention to what each of them gives to his feet, where all the nerves of his body end.

This forest, he has seen nothing like it.

He continues to walk through the trees till he reaches that place of luminescence. There are no more tamal trees here but two tall palm trees stand together, and one a little further away, alone. Beyond, there are dark hills. The traveler looks up and sees very few stars. Then he knows this is that faint glow of the entire upper atmosphere that surrounds the earth. It is created by reflected starlight, moonlight, man made ultra violet rays, and molecular processes. When seen at night it is called nightglow. He knows that scientists have been measuring nightglow, sometimes by sending up instruments in helium balloons which move around the world over a period of fourteen days. He stops walking.

He looks at the light which is itself, and not a means to looking. It does not confer clarity on things. He lies down on the ground because this light has taken away his will, given it time to rest. It is the first time he sees how much will even a traveler uses up. He looks at the light. It is an extreme serenity, but when it falls on him it does so with a different, immeasurable consequence. It pries things loose, makes them rise and shift, and brings to the consciousness movements never before felt.

He hears laughter, and when he opens his eyes he sees a little girl looking down at him. She stops laughing all of a sudden, and says, “Are you lost?”

“No,” he replies, sitting up.

“You’re lying,” she says, her voice curving on the second word.

“And you?”

“I’m just playing.”

“By yourself?”

She nods her head.

“It’s possible here,” says the traveler.

“It’s possible everywhere,” she says. “Let’s run.”

She laughs as she runs, in the way that children have, without reason.

She stops suddenly and stands close to him. She smells of fruits and leaves and mud. “Do you like this light?”

“It takes away my fears.” He reaches out to take her hand. But she moves away, out of reach.

“What kind of fears?” She bends her head to the left and looks at him. He cannot see her eyes clearly in the darkness.

“Many. The fear of being high up in an airplane. The fear of being shut in an elevator in a tall building. Who are you?”

She begins to laugh again. She runs, this time into the shadowed darkness of the trees. Her arms are spread out and she touches the tree trunks as she runs. She comes back, panting.

“This night shelters, it protects,” she says, still catching her breath. She stands very close to him. She has large, dark eyes, black hair, brown skin. On her bare arms and her slender throat there are scratches, perhaps from thorns.

“Did you get hurt?” he asks, pointing at the scratches.

She offers no answer, only continues to look at him.

“Let’s walk,” she says.

The traveler stands up. The light falls on the ground after the line of trees and reaches till the edge where the land plunges downward. There is perhaps a gorge below, with a slender river, he cannot tell. The hills across are dark, and as he walks on this strip of light, he feels he is on an edge of the world.

“It will be so different in the morning,” he says.

“There is no morning here. There is only what you see now.”

The traveler continues walking, but he slows down. He looks at the girl, and reaches out again to take her hand. Once again, she takes it away.

“There have to be some places where there is nothing but serenity,” she says. “Nothing but beauty and its strength.”

He looks around him, as if to test the truth of this. There is nothing to prove it wrong.

“Where are you going?” she asks.

“I don’t know. Wandering perhaps. Leaving things behind. I don’t know.”

The little girl is quiet as they walk. A few moments pass and she stops. “Can you carry me?” she asks.

The traveler, surprised, bends down and picks her up with ease, and she sits, light and slender in his arms.

“What is your name?”

She puts her arms around his neck. “Tara.”

“The ground here is comforting, soft but firm,” says the traveller as he walks.

“It is from the time that these hills and valleys came into being. What a time that must have been. To be present when something comes into being…” She is silent, looking at the sky ahead.

“This landscape is like a hand upon the brow,” he says.

She points to a place where the land protrudes so that three sides drop away into the darkness. “Let’s sit here,” she says.

They sit down, and the little girl hangs her legs over the edge and swings them back and forth over the deep darkness below.

*

The Museum Rietberg is on a hill. The traveler walks up from the main road, onto Gablerstrasse, a narrow, rust colored cobblestoned street going uphill. Ahead of him is a low, grey sky, moving continuously with its clouds. It is April, and there are patches of snow on the cobblestones. Water from the melted snow makes the stones shine. On Gablerstrasse, the traveler passes the Villa Schonberg on his right. The composer Richard Wagner lived here for some years. It was here that he composed Tristan and Isolde. Opposite Wagner’s home is the Museum. The villa, which is now the main museum, came into being as the home of Otto and Mathilde Wessendonck. It was they who gave Wagner and his wife a home in the half timbered house beside their villa. Wagner had fled to Zurich as a refugee in 1849. He called this home “his asylum on the green hill.” It was for Mathilde Wessendonck, with whom he was in love, that he wrote Tristan and Isolde. He gave her the draft score on New Year’s eve 1857, with a poem dedicated to her.

“Full of joy, empty of pain, pure and free, forever with thee.”

In a letter to Franz Liszt, Wagner wrote: “Never in my life having enjoyed the true happiness of love, I shall erect a memorial to this loveliest of all dreams in which, from the first to the last, love shall, for once, find utter repletion. I have devised in my mind a Tristan und Isolde, the simplest, yet most full blooded musical conception imaginable, and with the ‘black flag’ that waves at the end I shall cover myself over—to die.”

In Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde the world of day is the world of unreality, where the lovers must deny their love. The realm of night, in contrast, is intrinsic reality, where the lovers can be together, where their desires reach fulfillment; it is the realm of oneness, reality, truth.

Details come back to the traveler from the days of his adolescence when he learnt the music of the great European composers. He stops for a moment at the gate of the villa, a black wrought iron gate, locked with an enormous padlock. He looks into the grounds which seem darker than the street, as if many more shadows have gathered there. He sees a stern, black bust of Wagner on a white pedestal. Somewhere, as his life moved into adulthood, the traveler turned towards a different music, he began learning to play the rudra veena.

He enters the gate of the museum. On either side of the wet road plants have begun to awaken and sprout. In front of the villa is a tall, lean man with a kind smile. They greet each other. The traveler sees that the museum is two buildings, one the main villa and, another, a smaller villa, some distance away. In its entirety the man tells him, the grounds cover 67,000 square meters. They walk past birch trees and fir, patches of water under the trees. They enter the villa and go down in a small elevator directly into a vault with steel drawers and bright white lights.

There the tall gentleman brings out the paintings, one by one, hundreds of them. This is the largest collection of Pahari paintings in the world. He begins from the 1300’s, taking the traveler back to some of the sources of the paintings that both he and the traveler have found hard to live without. The traveler stands there for hours because there is no room for chairs in that space, and because he could not have sat down while looking at these paintings. “Are you tired?” asks the tall man once, and the traveler is so far from tired that it takes him time to understand the question. He knows these paintings were meant to be held in the hand and looked at over hours, and there before him right now is Raja Balwant Singh of Jasrota looking at a painting which his court painter Nainsukh has brought him, sitting with his legs folded underneath him on a wide, ornate chair, while dusk falls forever from the sky onto the trees outside.

But the traveler cannot sit down, not now, not in a vault, not in this time and age, not when he has come so far. Standing, and bending his head towards the paintings is the only posture that seems correct.

And so he looks and looks at the paintings of love in its infinite gestures, of gods, kings and sages, ashrams and courts, palaces on the crests of hills, he sees solid colors and flat planes, the blurred archetypes of trees, the single white curve that denotes the river, he sees all this change into rounded horizons, paler hues, trees and flowers and plants that can be identified in all their real blossoming details and multiplicity, and the river swirling with its currents of water, fish raising their heads for a moment, once even a boat, and yet the immensity and the reticence of the paintings unchanged over centuries. He had not expected the quietness of color that he finds in them, so much less bright than in books, so much more restrained.

They go up in the small elevator again and the tall man takes him to an upper gallery, where at one end, under a glass case, he shows the traveler the brush made of squirrel hair those painters would have used, the color yellow made from the urine of a jaundiced cow, the blue from fresh indigo, and most of all the glowing, dark green jewel of beetle wings used to decorate Krishna’s crown.

After this the traveler sits, on a wooden seat, placed before a large, arched window. He sees nothing, thinks of nothing. He does not lean back. He remains at the edge of the seat. Very slowly he begins to notice the mist that hangs outside over everything, grey with a faint silver light within. Birches with their slender white barks float on this mist, as if without roots, their branches still bare. He sees that the tall man has left him alone. The land is flat directly outside the window but after a few meters it begins to slope downward to the valley. A wind blows and shakes the thinnest, barest branches, some of them mere wisps of wood. It reminds him of a few strands of Radha’s windblown hair as she waits in the forest. Perhaps the breeze comes from the other bank of the river, finding its way through the mango grove in which she sits. Now the mist moves and begins traveling westward. This is how things are placed next to each other now, without warning, geographies and times buttressing one another. Down in the valley below, the moving mist reveals the slate roofs of buildings and the tall spire of a church, Zurich. His mind is flattened into silence, beaten down like a sheet of pure gold.

On his way out, he walks very slowly down Gablerstrasse. He steps with unprecedented concentration between the patches of snow, placing each foot firmly on the cobblestones, as if otherwise he would begin to hover over the ground. In earlier years the traveler had feet that would slip at the slightest moisture or the smallest pebble, he would often stumble, sometimes fall. But there came a teacher who made him stand, every day, with legs apart, knees bent, feet strongly on the ground. He said, “Now close your eyes and imagine your feet on grass, beneath the grass a firm soil, beneath the depth of this soil the first layer of the inner earth, then all the further layers, right till the centre, and then feel yourself standing, grounded, on the whole earth as it turns slowly under your feet.”

When the traveler reaches Seestrasse, he stops and waits for a tram.

*

This is an excerpt from a book length fictional work in progress called “Sub-continent.” The work is in five movements, each one unfolding in a different landscape, with changing characters. The unity in the work is subterranean, and emerges above the surface only sometimes, mainly in the form of a traveler, who is more a consciousness than a character.

As with other writings of Sharmistha Mohanty, one experiences in this essay a calm opening, a widening of space, an invitation to see the world with the author but on one’s own terms. How an author can do this I do not understand, but I experience this sensation every time I read her work.

Sharmistha’s prose composes several partitions like in a musical composition. Surely, this is new in Indian

English fiction. Great debut, audacious attempt and promise of a trail blazing career. Kudos and greetings from

Paris. INASU

Art is manifestation of creativity embedded in innocence derived from sensitivities. Art is what comes out of the vital centers of being rather than formulated or mechanical tendencies to represent artist’s cult and capabilities. This tendency is sharp among children for their innocence and exploring nature of peeping through their inward eye which with the advancement of age gets polluted and powerless. Art is a special stream which has its roots deeper than other contemporary streams and therefore it has a definite set of rules and regulations and institutions where in it is taught and explored. The phenomenon of art as process is not bound to forms and formulas but it is freedom from systematic and mechanical discourses. A line drawn, a point pierced in to a sheet, a stroke of brush or a splash can be considered as a complete work of art.