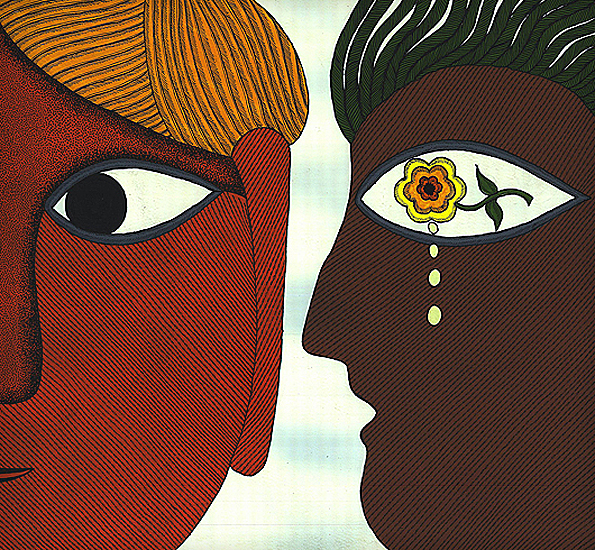

An Ambiguous Journey to the City: A Dialogue with Ashis Nandy

(By Ashutosh Bhardwaj and Giriraj Kiradoo)

1.

Pratilipi

An Ambiguous Journey to the City reworks the myth of the journey to explore the South Asian interface of city and village. You have argued that, in spite of their modest acquaintance with village life and manners, Gandhi and Satyajit Ray could discover their own villages because they were already there – either in them or in their audience. Do you see such a latent village in the contemporary imagination or personalities? Or have we lost them permanently?

Ashis

They are not perhaps permanently lost, but there is certainly a decline in the imagination of the village. I do see such imagination in the likes of Mahasweta Devi. Like Gandhi and Ray, she is also a direct product of cities; she was born in a city and has been brought up mainly in cities. But she has been able to invoke and mobilize our imagination of the village in a way that touches the village of the mind of those who live in villages.

To give example from another sector of life, scholar-activist Vandana Shiva is also a city-bred woman, educated entirely or almost entirely in cities. Nevertheless, when she talks of villages it makes sense not only to those who stay in cities and are acquainted with villages but also to those who stay in villages or are entirely products of rural India. I can make an almost similar case for Medha Patkar. But such people are increasingly becoming exceptions rather than the rule. In Indian cities and the dominant urban culture in India, the village figures less and less as a trigger or pivot of creative imagination.

In its new incarnation, Indian civic sensibility bypasses the imagination of a village or tries to be its total negation. The village now makes sense mostly as a target of social engineering, political reform and technological upgrading, but not as a way of life. Not even as a reservoir of cultural resources or as a baseline for social criticism of Indian urbanity.

Pratilipi

M.N. Srinivas, on the other hand, was forced to take refuge in the imagination of the village. You have argued that the three most influential modern ‘representations’ of the Indian village – Gandhi (politics), Ray (cinema/art), Srinivas (social science) – were products of creative imaginations, new ‘mythologies’ that reflected a specific aspect of South Asia’s tryst with colonial modernity.

Has the village as self not been lost permanently behind these mythologies and hence all the journeys to and from it have to end only in despair and ruins? Is it lost not only for the explicit ‘outsider’ (the educated, uprooted urban middle class) but also for the obvious, resident insider?

Ashis

First a clarification: These highly creative persons were not forced to take refuge in the village, as you put it. They were neither trying to ‘improve’ the village as a part of their professional responsibility nor were they seeking in the village a way of escaping the city. They invoked the village as a legitimate part of our vision of a good society and as a counterpoint of the city. They had to talk of the village as a way of talking about themselves and their own ideas of India. If the city is a form of standing criticism of the village, the village too has always been a powerful criticism of the city. Traditionally, their differing rhythms of life, different styles of sociality and public life, and different patterns of creative self-expression generated much of the inner dynamics of our civilization. The colonial city broke the dyad by trying to be a total negation of the village. This too had, at least at the beginning, something to contribute to our cultural repertoire but gradually that negation has led to an imagery of the future in which the village does not even figure.

In other words, we have taken that negation closer to its logical conclusion. In our imagination, the village is no longer a crucial counterpart of the city. The city now goes to the village primarily as a developer, planner, ruler, marauder and a functionary of the law-and-order machinery. On the other hand, the village mainly enters the city primarily in the form of ghettos and slums. For people like us, villages do not exist, except in fiction, poetry, cinema, ghettos and slums – as proxy villages in the last two instances – and these proxy villages, too, immediately unleash fantasies of ‘clearance’, ‘removal’, ‘retooling’, and ‘elimination’.

The new presence of the village in the city is packaged in such a way that the kind of sensitivity Tagore or Ray had towards the village is no longer available to us. It survives in a few writers like Mahasweta Devi and U.R. Ananthamurthy or in half-forgotten activist-thinkers like Sundarlal Bahuguna and Narain Desai. And they are all getting on in years. But then, there are also fortunately the likes of Medha Patkar, Claude Alvares and Vandana Shiva.

Pratilipi

But this imagination in contemporary personalities appears highly romantic, instead of creative. In Ananthamurthy we find it’s nostalgic. When he says that “Bhartiya medha” exists only in villages and little can be expected of the city-bred, he also reduces the possibility of a two-way exchange.

Ashis

There is nothing nostalgic or romantic about the two novels of Ananthamurthy I have read. When we are living and acting out an urban existence that assumes that Bhartiya medha exists only in the cities and, on the basis of that assumption, destroying the life-support system of more than two-thirds of all Indians, when we are unwilling to grant the minimum dignity to the majority staying in villages, what Ananthamurthy has said is the only moral and political option left to sensitive, compassionate Indians. Since Ananthamurthy talks of the village he has to offer a criticism of the city. That is the traditional job of the Indian village. It completes the idea of the city. Such criticisms are crucial.

I admit that the traditional job of the city too has been to offer a criticism of the village. But today that criticism is no longer a criticism; it has become an arrogant hectoring – a victor’s judgement and a conqueror’s verdict, legitimized through intellectual Kangaroo courts.

Pratilipi

Complementary criticisms?

Ashis

That’s right. Traditionally, people went to cities for official work, trading or pilgrimage. But that kind of relationship weakened when the colonial city came to India and the modern city was defined as an anti-village or non-village. The presidency towns began as colonial outposts and something of that cultural arrogance has survived and is, now, triumphant. Everything of a village has to be now compulsively negated. This gets support from the culture of modernity that endorses the ideas of the civic, the civil and the civilized as ‘naturally’ superior to the ‘rustic’ and the ‘uncivilized’. At most, we can patronizingly call any positive depiction or invocation of the latter patronizing and romantic.

Pratilipi

What, for us, the city-dwellers who neither are dependent on villages nor have any creative imagination, is the contemporary relevance of villages?

Ashis

The village, because it is a counterpart of the city, is a reminder to us of the limits of the city – the limits of contractual relationships, impersonality, anonymity and individualism. It reminds one that there are things called community, nature, family and kinship ties, primordial relationships, intergenerational relations, and global commons, perhaps even – and this itself is a balancing factor in any society that seeks to be humane. If you are left with the city as the beginning and the end of the idea of habitat, if you cannot think beyond the city, beyond the present state of the city, it then becomes difficult – perhaps impossible – to even think of a different kind of the city.

Pratilipi

Do you foresee any future for villages in India?

Ashis

Yes. We cannot erase the village from India’s map that easily. Though at the moment, we openly opted for the American model. They don’t really have villages there and we are bedazzled by that achievement. Chidambaram has said that we want 70 per cent of India to get urbanized. That is not a healthy way of looking at the future. If you ignore city-states, a country that only has cities and no village is culturally maimed. In any case, I don’t think India can bear the load of 100 per cent or for that matter 70 per cent urbanity– ecologically and socially.

Pratilipi

But aren’t we moving in that direction?

Ashis

Yes, because the idea of modernization presumes continuous urbanization and such urbanization is seen as an inescapable part of industrialization. I believe that this uncritical attitude towards the urban-industrial future has created a void in our vision of the future. When we think of the future, most of us don’t think of a disjunctive future. We begin to look at the future as a linear progression from the present. This has suspended the play of imagination and the possibility of experimentation.

Pratilipi

Most of the economic measures by the central and state governments over the last two decades have invariably aimed at converting villages into cities.

Ashis

The traditional idea that the city and the village are counterparts of each other has engaged them both in a spirited dialogue and mutual criticism and enriched both. The dialogue and the criticism have constituted a healthy baseline of social criticism among ordinary citizens and made them recognize the limits of the urbane and the pastoral. The moment you say that the pastoral must be obliterated because it is incompatible with development, industrialization and progress – as if development, industrialization and progress were sacrosanct, absolute or non-negotiable values – you subvert these ideas of limit and erase the possibility of a serious dialogue on our future.

Pratilipi

The new avatar of global capitalism has produced a new territorial mythology of village, that of the Global Village, a myth that presupposes the shrinking of space and time. How is it changing the description of the inner exile, especially of the metropolis?

(Note the term ‘Global Village’. Whoever coined this term could have also said ‘Global City’. Out of sheer contempt for villages, we are striving to convert them into cities but still dream of a ‘Global Village’. Some nostalgia here? Does it mean that an ideal world cannot be a global city or global metropolis, it has to be a global village?)

Ashis

That is a very insightful remark. I agree with you. At one time, one could think of a global city. Theologian Harvey Cox wrote on ‘The Secular City’. City secular ho sakta hai, lekin global village hi hona padega because you are trying to introduce at the global plane the ideas of interpersonal warmth and global commons, things outside your nuclear family or children. And this is not possible within the impersonal anonymity of a city. The metaphor of the global village is based on the hope that deeper forms of human relationship will ultimately prevail in the city. Nostalgia and the romantic invocation of the village can be healthy, socially and psychologically. I don’t consider it regrettable or pathological.

2.

Pratilipi

You mentioned Mahashweta Devi but don’t you think that in the last few years she has allowed herself to be carried away by her fascination for villages and the forces which may represent the regressive in villages? She allowed people to equate herself with the People’s Committee Against Police Atrocities (PCAPA) and its boss Chhatradhar Mahato…

Ashis

Why shouldn’t she? She has always been a Marxist. At the beginning, she was a conventional Leninist, terribly conventional. It took many years for her sensitivity to the problems of tribal and rural India to deepen and this deepening sensitivity pushed her towards her present position. The callousness of successive regimes in India towards our tribal population contributed handsomely to her transformation; she really couldn’t have moved in any other direction.

Let us have the honesty to admit that, whatever our rulers may claim, we have treated our tribals very shabbily over the last 60 years. We now glibly say that the Naxalites do not believe in the Constitution but can anyone say with a straight face that our policy makers and parties have remained faithful to the Constitution and lived by the guarantees and the protection it promised to the tribals? The various Indian regimes were the first ones to make a mockery of the Constitution; the Maoists came later.

Pratilipi

Are you suggesting it is inevitable, a natural conclusion for her, or people like her, to side with such outfits, despite knowing that it would perhaps do no good for tribals?

Ashis

No, they are only hoping that the Maoists will bargain more honestly on behalf of the tribals. Personally, I have great doubts about the rhetoric of revolution. In our times, it has only led to massive bloodshed and resilient police states and has had no lasting impact. Even in Russia, where the Communist Party enjoyed absolute power for eight decades, the revolution has left behind nothing much to boast about and much that the party should be ashamed of. Perhaps the only important ‘gain’ from the Russian revolution has been the steadily declining growth rate of the Russian population. They killed so many people that they created a permanent problem of declining population for the Russian society. Look at the way the Chinese and Vietnamese revolutions are now unwinding.

China’s rulers have been intelligent enough to jettison the rhetoric of revolution but, in the name of revolution, they have in the meanwhile saddled China with a closed polity and a police state.

Pratilipi

So you don’t trust the claims of Maoist organisations.

Ashis

A revolution doesn’t care for or depend on anyone’s trust or distrust. But yes, I do believe there is always an inevitable process of decay or decomposition in a long-lasting, violent, mass movement and all revolutions too, unless they are very short-lived, invariably lead to authoritarianism, surplus violence and degradation of those who begin the violence. Revolutions begin as ideologically driven struggles, but gradually the ideology becomes a façade for the naked exercise of power and the sadistic pleasure of pursuing violence for the sake of violence. Revolutions, I have now come to suspect, not only eat up their own children but always brutalize a society and, paradoxically, make lasting revolutionary changes impossible.

Pratilipi

You have remarked that the Naxalite Maoists of the 1970s, after beginning with an intention of ‘surrounding and defeating the city’, quickly converted their movement into a ‘journey of self-discovery from the city to the village’. But this is no longer correct. Those who constitute the present conflict are no longer urban disillusioned youths, but mostly tribals and villagers, though their case is being spearheaded by urban intellectuals.

Ashis

This phase of the Naxalite movement is actually an uprising or rebellion of our tribal population. Their pain, desperation and rebelliousness have been used by urban ideologues. To act ideologically, I sometimes suspect, you have to be urban. Tribals living in a community usually have only faiths and beliefs, not ideologies. And I am suspicious of all ideologies because ultimately they become manipulative. As it happens, the ideology in this instance has come not from tribals living in forests, but from outside. No wonder the leadership of the movement still remains with literate, urban activists. I don’t believe that the Naxalite movement has produced any tribal leadership; those with tribal names are all deracinated tribals. They too, like Chidambaram, want to turn the tribal communities into floating masses of urban proletariat. Only they want to do so for the sake of a mythical Indian revolution.

Yet, at the same time, their movement is a response to genuine grievances. Our whole model of development and modernization is a negation of everything the tribal cultures have stood for. Apart from the brutal and open exploitation of the tribal communities, our idea of progress has taken away the dignity of these communities. The conventional idea of progress has no respect for tribal lifestyle and worldviews and its tacit message is: we don’t respect you and it’d be better if you all die out, for then we should be able to celebrate your culture and practices and store you music and art in our museums.

Pratilipi

But has not this movement been hijacked by those who have little to do with tribals?

Ashis

When you resist powerful state machineries, you cannot be choosy about your allies. But yes, in their desperation the tribals have probably allowed their movement to be hijacked by those whose vision is an urban utopia. It’s a tragedy that Indian radicalism has never learnt anything from India. Though there are clear Luddite elements in the theoretical edifice of the Naxals, ultimately it too is a celebration of nineteenth-century, European, urban-industrial vision, with the implicit message that the tribals must move out of their primitive communism and become real, adult, trade-unionized, socialist workers in India’s booming industries.

It also means that in any confrontation with the state, the tribals are the ones who will die and the state too will employ other tribals to fight their rebellious brethren. It will, for all practical purposes, become a civil war for the tribals. That’s the situation in India today. And Indian radicalism has shown hardly any awareness of it.

Pratilipi

It has become a commonplace thought, these days, that violent resistance is the only effective way out in India since the state has rendered all non-violent movements ineffective. In your last interview with Pratilipi you talked about your renewed optimism about non-violent resistance. What role do you see non-violence playing in a scenario like this?

Ashis

I now consider non-violence to be much more foundational in human beings. This is not a personal faith. I say this on the basis of existing social, psychological and ethological knowledge. But for non-violence to work, you need another kind of theoretical model and philosophical sensitivity. At the moment, both parties – the government and the Maoists – are hostile to the idea of non-violence.

The real politicians though, because they — unlike the bureaucracy, the technocrats within the cabinet, and the media – are de-ideologized weathercocks can opt for non-violent solutions more easily than the ideologues can. Remember the agreements that Indira Gandhi signed with the Nagas and the Mizos and the one Atal Bihari Vajpayee came close to signing with Nawaz Sharif? If the Left is thrown out of Bengal in the 2011 Assembly polls, do you think Mamata Banerjee will allow Army action against Naxals in Bengal? There are crosscutting demands and pressures in Indian politics. Political compulsions may force you to compromise even when you do not believe in non-violence. And politicians being politicians, even Chidambaram might begin wearing his khadi vest more regularly and start singing paeans to non-violence. Only Shekhar Gupta and Arnab Goswami might be left holding the fort for India’s future bauxite kings and steel tycoons, though the latter might by then move to other more lucrative ventures.

Pratilipi

A personal question: In Mrinal Sen’s case, you talk about the problem of speaking for others. In a way, your writing also speaks for others. Indeed, all writings, expressions, speak for the other. What form does this problem take for you when you choose to speak for those who are challenged by urban modernity? Do you ever see yourself as someone psychologically exiled?

Ashis

I can answer this question in one sentence. All my research and all my writings are a form of self-exploration and the exploration of my kind; I am a traitor to my class, because I feel that my class – the urban, modern, middle class – has not done its job and the Indian middle class as a whole has betrayed its own past and become flabby, risk-averse, and intellectually lazy.

God bless Ashis Nandy!

IF AM WRONG THEN GO TO ANY VILLAGE IN INDIA FIND FOR YOURSELF.