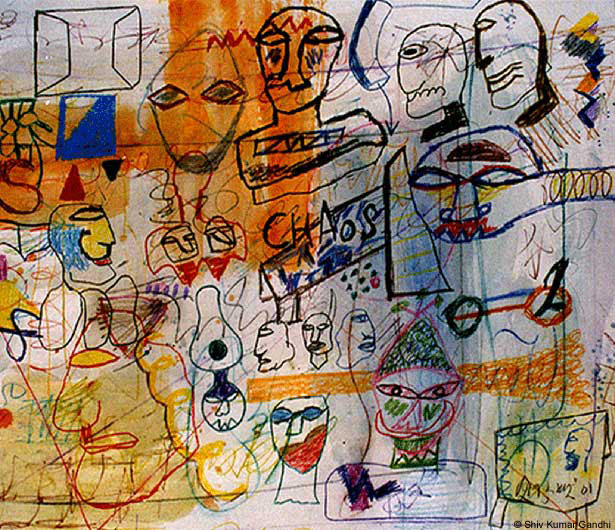

A Fragment Of The Broken Mirror: Krishna Baldev Vaid

Just as I’m about to give up pacing and go back and sit down, I see Mother – or her ghost – right in front of me… oblivious of everything… walking toward me without even seeing me. Maybe she’s sleepwalking, looking for me in a dream. If I step to one side, she’ll stagger by. Has she been the one moaning? Maybe pain has altered her voice. I’ll speak to her. My own voice sounds different. As soon as she hears me, she sits down as though under order, holding her head with both her hands… like Father. Was that Father’s moan I heard? I go sit next to her. She starts crying. Like a self-controlled old woman. This isn’t her way of crying. She can’t cry without throwing a fit. But now she’s crying without a sound, without twisting her face. Maybe Aslam’s mother cries like this when she thinks of her son – that is, if he’s dead. Maybe she thinks of me, too. A little. Hafeeza, too. I edge closer to Mother and put my arm around her neck. She starts to scream – as if I was strangling her – and then suppresses it. This isn’t the way she normally screams, either. When she screams, there’s no stopping her. She is scratching her throat at the same spot again and again. I withdraw my hand. She continues to sit there, with her head between her hands. She’s tired. But this isn’t the way she normally gets tired. Even when she’s dead tired, she can’t help lashing out with her tongue at the whole world. Maybe I should tire her a little more so she might get some sleep. It probably makes her cry to see the others and their belongings. Most likely she’s thinking of her own bundle. Or she’s crying at seeing me – tears of joy. Why can’t I cry? Or laugh? No joy, no sorrow. I’m incapable of crying now. What’s happened to that old man and his moans? Maybe I was hearing the moans of a ghost which wanted to see if anyone recognized the sound of its voice. I don’t believe in God – so how can I believe in ghosts? This isn’t the time for questions of belief… Mother doesn’t need me right now.

As soon as I get up, she grabs my hand and pulls me down over herself. I regain my balance and squat facing her, like herself, bending forward, as if we were about to play marbles. I hope she doesn’t break into a marble song now that she’s stopped crying! Remembering times gone by – her childhood when her father married her off and her girlfriends were still playing marbles… Father, too, must have been a mere lad then. He’s never talked to me about those days, although he must have a lot of memories. Alone, he must feel gloomy after drinking. But now he’s stopped drinking. Which may be why he’s always depressed… Perhaps he’s crying, too, sitting with Devi. I should somehow coax Mother to show me where they are. Then we can all cry together, like a happy family. But Mother looks as if she wants to cry some more. And then talk some…

As if she’s read my mind, she suddenly starts talking, but not in her usual way. Her voice is so clear and dry. It’s as though she’s been purged of all her impurities and longings. As though there wasn’t a single tear left in her eyes, nor a desire in her heart. As if she’s sitting on another shore, beyond joy and sorrow, where everything looks at once familiar and strange. The words aren’t hers, either. It’s as if an old recluse dressed up as Mother is reading the news in a hollow voice. I listen regardless of the horror of the message… They killed Melay Shah. They killed Wrestler Vishwa. They killed Old Maya. They killed the priest at my temple. They killed the blind beggar. They killed Prem the Paan Wallah. They killed Sheeta the Kulfi Wallah. They killed the Brahmin woman who came to our house for alms. God knows what’s happened to her daughter. They killed Keshav’s father. They did every conceivable thing to his mother. She’s still bleeding. All her clothes are soaked in red. God alone knows about Chambeli. They killed her husband. They hacked Melay Shah to pieces. Kumari and Dari saw it with their own eyes. At Melay Shah’s house before they came to the shed. Bakka and Butcher Rehmat did everything to Kumari right there, in front of Melay Shah and Dari. Then they killed Melay Shah in front of Dari and Kumari. Old Maya’s body is still lying in the gutter. They killed that crazy In-Other-Words. They killed Lord Legless. They killed the baker. They killed his Hindustani wife. They killed even their parrot. They killed Cougher Shah. And his wife. And all their grandchildren. They killed Hara the Confectioner. God knows what they did to Nooran. They killed Weaveress Phalo. They did really terrible things to her too. They killed Himmat Singh. He and Phalo were hiding together. They killed Paro’s mother. Her body is still lying in the gutter. They killed Emperor. And his horse. They killed Hardayal. And his mother. And his father. They killed Giani the General Merchandiser. They killed Jita. Balo is alive, but you can’t recognize her. They did terrible things to her. She’s lying there with her mother, smeared with blood. Her mother’s all right. God knows what they’re muttering about. Sometimes they mention you… sometimes Jita… sometimes Hardayal… sometimes Asloo. Balo keeps trying to take her clothes off. Her mother keeps laughing. They killed Shastriji. They killed they Pakora Wallah. They killed Raja’s mother. God knows what happened to Raja. They killed the Puffed-Rice Wallah. They killed Headmaster. And his wife. God knows what happened to his daughter. They killed Doctor Chamba. God knows where his wife is. They killed Dr. Allah Ditta. They did terrible things to his Iranian women. They killed Melay Shah. They killed Wrestler Vishwa. They killed Old Maya. They killed the priest of my temple…

*

I don’t know how long it was before I got up. Mother was still speaking in the same clean and dry voice. Once Ravana told us the story of Hamlet – how the stage is littered with corpses at the end. Thinking of that stage I started slouching around again, like someone else’s ghost. I heard a granular wail that arose in the early morning light and stopped abruptly every few seconds. Maybe it was the same old man moaning in a different voice now, sounding like a sick joke or a sharp taunt, or like an aged child hiding in a corner imitating a nanny goat in order to amuse the famished and mutilated survivors or to incite them or perhaps to tell them that their cries were meaningless, their suffering in vain. Forgetting everything else, I started to focus all my attention on that goat-like granular bleat, as if the essence of all human sounds had been reduced to that one sound. At each vibrant installment of the bleat, my face contorted into a grimace before it was disfigured by nausea. I’d held my breath and waited for the next installment, like a person buried under the debris listening to the last twitters of a sparrow also buried there somewhere. Perhaps that granular wail wasn’t an aged child’s or a goat’s at all, but some other monster’s. Perhaps it was some deranged tune beyond any sick joke or sharp taunt, beyond past or future, beyond desire and hope, beyond noise and music. Again and again in the early morning light, it strained and jangled like a thin chain. Holding my breath, I walked toward a deserted corner where the wail seemed to originate, despite my fear that I’d see something monstrous – with the bleat of a goat and the body of some unknown animal.

But when I reached that corner, there was nothing there – just an abandoned baby writhing in pain, alone and naked, in a small pool of blood, oblivious of the Independence and anguish of her country, her eyes fixed on me… I stood there, unsteadily, gazing at her until her agony was over. Then I sat down beside her and started to cry.

Thank you, thank you Mr. Vaid. All the memories of my family’s partition agonies distilled in this gem.