दिसम्बर 2008 / December 2008

|

अगर हम मुहावरे में इसे कह सकते तो प्रतिलिपि का प्रत्येक अंक ‘आतंक के साये’ में निकला है. मई में जयपुर से नवम्बर अंत में मुंबई तक, हमारा अंक निकलने के आस-पास बम धमाके और ‘हमले’ हुए है. मुंबई के बाद यह समझा जाने लगा है कि आतंक अब हमारे अनुभव-तंत्र में प्रवेश कर रहा है. कि वह हमारे नागरिक और निजी जीवनों में दरारें पा चुका है. कि अब वह कुछ कायर, अज्ञात लोगो का उपद्रव नहीं रहा. मुंबई में और उसके बाद जो कुछ हुआ है, उसने हमारे सार्वजनिक जीवन के साथ साथ बिल्कुल व्यक्तिगत स्पेस में एक नए यथार्थ को घटित किया है. उसके बारे में मूलतः राजनितिक दलों की प्रतिक्रियाओं के अलावा जो नागरिक प्रतिक्रिया सक्रिय होती दिख रही वह हमसे लगातार आग्रह कर रही है कि हम इसे व्यवस्था और गुप्तचर सेवाओ की असफलता के साथ साथ सामाजिक विफलता के तौर पर भी, एक बौद्धिक विफलता के तरह भी देखें और सिर्फ़ राजनीतिज्ञों से ही नहीं अपने आप से भी एक समाज और एक व्यक्ति के रूप में साहस और आत्म-विश्लेषण की अपेक्षा करें क्योंकि हमारे समय में संकीर्ण सांप्रदायिक और जातीय राजनीति ने जो सफलता पाई है, उस् सफलता में हम सब का कहीं न कहीं हाथ है. अपने से भिन्न लिंग, जाति, धर्म, विचार(धारा), फैशन का इतना कम सम्मान, उसके प्रति इतनी कम जिज्ञासा और इतनी शत्रुता शायद ही पहले कभी रही हो.

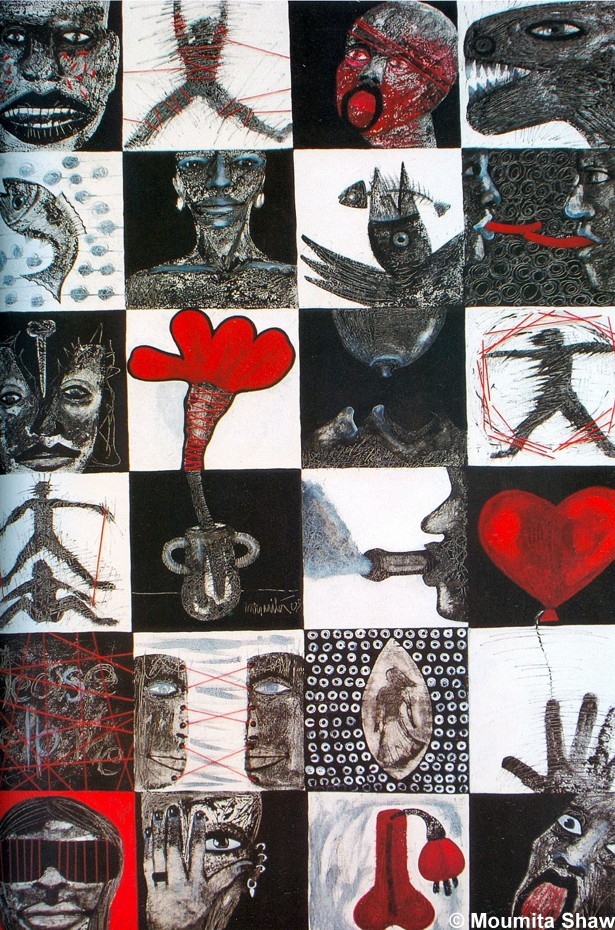

हम यहाँ यह फिर याद करना चाहते हैं कि अंजाम देने वालों और इसके पीड़ितों, दोनों के भीतर पहले से मौज़ूद, एक सोये हुए आतंक की पूर्वमान्यता के बगैर आतंक एक कारवाई बल्कि एक विचारधारा के रूप में इतनी व्यापक और स्वीकृत संघटना नहीं बन सकता था. प्रतिलिपि का अगला अंक, पहला वार्षिकांक, हमारे सामाजिक और निजी जीवन में आतंक के अनुभव और उसके प्रति हमारे रिस्पोंस पर फोकस करेगा. 2जैसा पिछले सम्पादकीय में कहा गया था, हमारे समय में अनुवाद के नये संकेतक/मध्यस्थ सक्रिय हुए हैं। भारत में, भारत के विषय में अनुवाद को लेकर सक्रियता अकादमिक और व्यावसायिक दोनों स्तरों पर नये ढंग से बढ़ी है। इस वर्ष के शुरु में सियाही ने अनुवाद पर एक आयोजन किया जिसका शीर्षक था ट्रांसलेटिंग भारत. उस आयोजन में भारतीय भाषाओँ के अलावा मुख्यतः फ्रांसीसी और ब्रितानी अनुवादकों और साहित्यिक एजेंटो ने हिस्सेस्दारी की. पिछले महीने स्विट्जरलैंड के लोज़ान विश्वविद्यालय में एक आयोजन हुआ जिसका शीर्षक था ट्रांसलेटिंग इंडिया. इसमें हिन्दी लेखकों, आलोचकों और इतिहासकारों के साथ साथ स्विस, फ्रांसीसी, जर्मन और अमेरिकन अकादमिकों ने हिस्सेदारी की. सियाही के आयोजन के उद्देश्यों में ‘आर्थिक महाशक्ति’ के तौर पर उभरे देश और ‘ग्लोबल हो रहे संसार’ में भारत से अनुवाद की संभावनाओं का पता लगाना, अनुवाद कर्म और अनुवाद उद्योग की समस्याओं पर विचार करना और भारतीय भाषाओं से अंग्रेज़ी एवं यूरोपीय भाषाओं में अनुवाद कर्म से जुड़े विभिन्न व्यावसायिकों को एक नेट्वर्किंग प्लेटफार्म उपलब्ध करना था. लोज़ान विश्वविद्यालय के आयोजन का उद्देश्य हिन्दी साहित्य के अनुवादों से निर्मित होने वाले ‘सांस्कृतिक भारत’ का अध्ययन करना था. लोज़ान का आयोजन अधिक औपचारिक रूप से वैचारिक/अकादमिक किस्म का आयोजन था और इसमें पढ़े गए पर्चे विश्वविद्यालय द्वारा प्रोफेसर माया बर्गर और निकोला पोज्जा के संपादन में पुस्तककाकार प्रकाशित होंगे. (इस आयोजन की अधिक जानकारी के लिए देखें साइड बार) उसमें पढ़े गए पर्चों में से पाँच हमारी शीर्ष कथा में शामिल हैं. प्रतिलिपि में उनके प्रकाशन की अनुमति के लिए हम माया और निकोला के आभारी हैं. इस अंक में प्रस्तुत छह पाठ अनुवाद और भारत के सम्बन्ध को कई तरह से पढ़ते हैं. सुधीर चन्द्र उन्नीसवीं सदी में उपनिवेशीकरण की पृष्ठभूमि में भारतीय संस्कृतिक आत्म के बनने की जटिल गाथा को कहते हुए यह याद दिलाते है कि कैसे आरंभिक भारतीय अनुवादको ने अनुवाद को एक दुधारी तलवार की तरह इस्तेमाल करने की कोशिश की जो शीघ्र ही एक ‘एपिस्टमोलॉजिकल सबमिशन’ में बदल गयी. मदन सोनी का पठन हिन्दी गद्य की जन्मकथा को एक औपनिवेशिक फलन की तरह पढता हैं और उसकी उपनिवेशोत्तर जीवनकथा को समस्याग्रस्त करता है. पुरुषोत्तम अग्रवाल कबीर के उपनिवेशकालीन और उपनिवेशोत्तर अनुवादों को डिकोड करते हुए यह पाते हैं कि इन अनुवादों में कबीर अनुवादकों के अपने पूर्वग्रहों से निर्मित एक भिन्न कबीर है, एक भिन्न कवि ही नहीं, भिन्न व्यक्ति भी. एनी मोंताउ का पेपर निर्मल वर्मा और कृष्ण बलदेव वैद के कथा साहित्य को, और खुद उनके द्वारा किये गये अनुवादों को भारतीय और पश्चिमी दृष्टियों की रोशनी में पढता है. गिरिराज किराड़ू तेजस्विनी निरंजना की पुस्तक को पढ़ने के प्रयत्न में उत्तर-औपनिवेशिक प्रश्नो को हल करने में उत्तर-संरचनावादी ज्ञान पद्धतियों के उपयोग और अनुवाद के सम्मुख मूल की स्थिति पर विचार करता है. इन पाँच मुख्यतः अकादमिक मज़मूनों से बहुत भिन्न तरीके से इस प्रश्न पर विचार करता है गीतांजलि श्री का निबंध. द्विभाषी होने की औपनिवेशिक विरासत, वैश्विक साहित्यिक परिदृश्य में भारतीय साहित्य के ‘प्रामाणिक’ प्रतिनिधि के तौर पर भारतीय अंग्रजी साहित्य की विडंबनात्मक मान्यता और एक बहुभाषी देश की बहुल सचाईयों पर एक साथ निजी और सार्वजनिक ढंग से बतियाता हुआ यह निबंध एक द्विभाषी के एकांत में और उसके द्वारा लिखित ‘साहित्य’ में अनुवाद और लेखन की प्रत्यावर्तनीयता का बहुत महत्वपूर्ण विश्लेषण है. 3यह प्रतिलिपि का पांचवा अंक है. पिछले आठ महीने हमारे लिए बहुत-से सुखद आश्चर्यों से भरे रहे हैं. हमें उम्मीद है हम हर अंक के साथ कुछ बेहतर हो रहे हैं. पाँच अंकों में हमने तेरह भाषाओं के करीब 135 लेखकों का और आठ चित्रकारों का काम प्रकाशित किया है. हम उनके सहयोग के और पाठकों के बेहद शुक्रगुजार हैं. |

To resort to a cliche, each issue of Pratilipi has come out in the ‘shadow of terror’. From Jaipur in May to Bombay at the end of November, there have been bombings and ‘attacks’ around the time a new issue of Pratilipi goes online. After Bombay, it’s beginning to be said that terror is now entering the ways we make sense of our experiences. That it has found cracks in our public and private lives. That it is not the work of some craven, ignorant people. What happened in Bombay and after, has perpetrated a new reality in both out public life and in our personal space. Besides the political reactions, the reaction of the citizens insists that we see this not only as a failure of intelligence and political system but also as a societal failure, an intellectual failure. That we must demand not only from our politicians but also from ourselves – as a society and as individuals – courage and self-analysis because, in one way or another, we are responsible for the success that narrow communalist and casteist politics has found in our time. There could hardly have been a time when there was so little respect, so little curiosity and so little tolerance for differences in gender, caste, religion, thought, ideology, etc.

We would like to reiterate that terror as an act or even as an ideology, could not have become a pervasive and accepted phenomenon without presupposing some kind of prevalent, sleeping terror in the minds of those who inflict it and those who suffer it. 2As was stated in the last Editorial, in our time, new signifiers/mediators of translation have become active. Whether academic or commercial, there seems to be an increase in activity around translation in India and about India. At the start of the year 2008, Siyahi organized a translation event titled “Translating Bharat” in which the participants included French and British translators, besides those working in Indian languages, and literary agents. Last month, there was a conference at Laussane University (Switzerland) titled “Translating India“. Participants included Hindi writers, critics and historians as well as Swiss, French, German and American academics. The aims of Siyahi’s event were to explore the possibilities of translation in India (an ‘economic superpower’ in a ‘globalized world’), to discuss the various problems in the process and the economics of translation, and to provide a platform for networking to people in the translation market. The conference at Laussane intended to study the ‘Cultural India’ created by translations. This event was obviously more academic in nature and the papers read here will be published in book form, edited by Maya Burger and Nicola Pozza (see sidebar). Pratilipi is grateful to Maya and Nicola for permission to print five of those papers as part of our Lead Story. The texts presented here read the relationship between translation and India in many ways. Sudhir Chandra, while narrating the complex story of the formation of modern Indian cultural consciousness in the context of colonization, calls attention to how the first Indian translators tried to use translation as a double-edged sword which soon turned into an ‘epistemological submission’. Madan Soni’s text reads the development of Hindi prose as fallout of colonization and problematizes its post-colonial history. Purushottam Agrawal, in decoding the pre- and post-colonial translations of Kabir, finds that, in these translations, the translators have created a different Kabir out of their preconceptions – not just a different poet, but a different person. Annie Montaut’s paper reads Nirmal Verma and Krishna Baldev Vaid’s fiction (and her own translations of that) in light of Indian and Western perceptions. Giriraj Kiradoo, in trying to read Tejaswini Niranjana’s book, problematizes the proposed project of using post-structuralist methods to solve post-colonial questions and of the position of the original vis-a-vis the translation. In ways very different from these academic papers, Geetanjali Shree’s essay approaches the same questions in a very different manner. It talks of the colonial inheritance of being bilingual, the ironic acceptance of the the Indian-English Literature as the only, authentic and noticeable representative of Indian Literature and the many truths of a country with many languages, in a way that is at once personal and general. The essay is also important in the way it talks of the interchangability of original and translation in a bilingual writer’s writing, and in her loneliness. 3This is the fifith issue of Pratilipi. The past eight months have been full of pleasant surprises for us. We hope we are getting better with each issue. In 5 issues, we have published about 135 auhtors in 13 languages, and have presented 8 artists. A big thanks, to them and to our readers. |

अनुवाद और अनुसर्जन पर एक मुकम्मल बहस आयोजित किया जाता तो अच्छा रहता.