Songs of the Ship: Surabhi Sharma

I completed my film, Jahaji Music, last year. What can I write about it now? Should I address the recurrent questions that came up during discussions after screenings? “Why does Remo Fernandes, an Indian Rock/Pop musician, star in a film on Caribbean Music?” “Why does Jamaica feature prominently in a film that seeks to explore the music of the Indian diaspora in Trinidad?”

And how do I respond to these questions in a note that’ll be read by an audience who, it is safe to assume, would not have seen the film in the first place? Jahaji Music (as is the fate of documentary films, more generally) despite being screened in nine Indian cities in the past year, would only have been seen by a niche set.

Rather than explain why these two questions came up as frequently as they did, I would like to explore what the questions signify – both for Jahaji Music, and for my film-making practice.

As a filmmaker I tend to make ethnographic films. I had never pressed the record button on the camera when I visited a place for the first time. I need to soak up a place, form a relationship with people, only then do I begin to think about the film I am making and its rationale.

I try to structure my films into a quiet narrative of a place and its people. My first film Jari Mari: Of Cloth and Other Stories was filmed in the large expanse of slums neighboring the Mumbai international airport. Aamakaar – Turtle People is about a tiny fishing village in North Kerala whose community resisted sand miners carting away the village estuary. Above the Din of Sewing Machines recorded labour practices in export-oriented industries that were unfair to the point of being criminal.

But this time it was going to be different. All I knew about the Caribbean before the shoot was through books, photographs and of course loads of music. We had no choice than to begin shooting from the day we landed. We were in Jamaica for a week and Trinidad for three weeks.

Remo’s presence in Jahaji Music, moreover, precluded the possibility of an ethnographic eye. He was a character ‘scripted’ into the film, so to speak. He did not belong, neither did we – there was thus no meaning to be made in watching, recording. Instead, the inherent tension of first meetings, the uncertainties of uncharted journeys, its expectations and disappointments, all this and more was what I was filming.

A seemingly complete film could have been made on the music of the Indian Diaspora in Trinidad: strains of Bhojpuri and Hindi film music in Chutney Soca could have made for a compelling story of migration, displacement and nostalgia. Except that, for me, that would have been a problem-ridden narrative, one that did not take into consideration the formation and assertion of the Indo-Trinidadian identity. A people hankering for their lost homeland would be, I knew, a false representation.

One of the members of a popular Chutney band in Port-of-Spain, The Gayatones, told us that they don’t know the meanings of the words of the songs (Mohammad Rafi and Kishore Kumar hits) that they sing at functions. But it does not matter, he continues. They are able to strike the right emotion. “We may not know the words at all, but it’s a part of we”.

We hear Mahi Ve from Kal Ho Na Ho in Gayatones’ studio. “So who wrote this song?” Remo asks. An independent musician, Remo, as he informs us elsewhere in the film, is not a fan of Hindi film music. But for Chutney musicians in Trinidad, it is difficult to reply to an Indian musician unfamiliar with the biggest hit of the season. “It’s a Hindi song err, from an Indian film err Kal Ho Na Ho“, stutters Rishi, the Gayatones Band member, who will overlay Mahi Ve with a dizzying array of electronic sounds.

Remo’s response to this track overwhelms the sequence. And Ramani, the cameraman of the film, pans across the walls to a photograph of a grandfather, or great grandfather, probably the person who came across to the island from India, and to a painting of a deity.

Without Remo in this sequence, the familiar would have been comforting: Kal Ho Na Ho, Hindu deities, a framed photograph of an ancestor in a kurta pajama. The tension in Remo’s meeting with Rishi pushes into the foreground the question: Who is an Indian? And what does the term ‘Indian culture’ refer to?

In the film, we are introduced to The Gayatones after having met Stacey, the Dancehall Queen, in Kingston, Jamaica. Stacey’s cultural legacy is black Africa. This, I believe, complicates the ‘we’ even further.

We were filming the matikor, a pre-wedding ceremony which ends with women dancing around the ceremonial fire. Traditional bhojpuri songs were sung, replete with ribaldry, somewhat recognizable to most north Indians. But then the dancing began. Any semblance of easy access that we, a motley bunch of Indians, had to the ceremony evaporated in moments. There was absolutely nothing in India that we could reference to make meaning of the dancing. It was the dancehall queens in Jamaica and the wining – a kind of pulsing and gyrating of the waist while dancing – of Afro-Trinidad that connected with the fantastic way the women moved.

I gave the title, Jahaji Music, to my film: Songs of the Ship. Ships that carried slaves from Africa to the Caribbean islands almost 400 years back. The ships also carried indentured labourers from India a couple of hundred years later. To the same set of islands, to do the same work on colonial sugar plantations, after slavery was abolished.

The indentured labourer carried with him his Jahaji Bundle, a bundle of meager belongings and a couple of seeds – mango, tamarind, pulses – onto the ship. S/he also carried her Bhojpuri music – songs of fertility to be sung at weddings and births, songs of gods and goddesses, songs of seasons, songs of the remembered homeland.

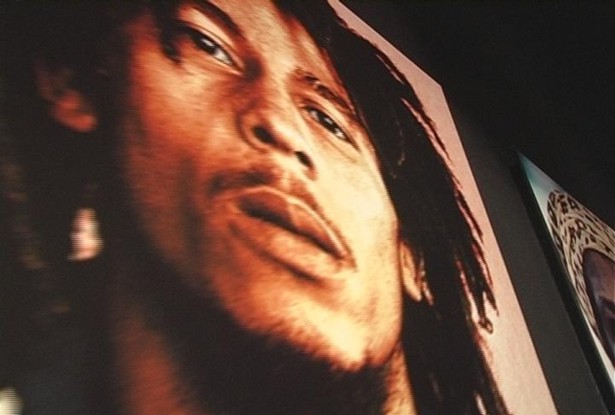

Songs of the imagined homeland in Africa, of 400 years of slavery, of wanting to fly away home, dot the soundscape of Jamaican reggae and dancehall music. The rhythm of the ships comes close to the slow tempo that makes up the Reggae Riddim. Riddims usually consist of a drum pattern and a prominent baseline. It’s a commonly used term in Jamaican Reggae and Dancehall music a genre of music that came out of the Rastafari movement in Jamaica in the 60s.

The Calypso music of Trinidad used irony to mock the colonial master, and today they target present day politicians. They sing songs of food and sex, covet the Indian woman and the wining Trinidadian woman.

Bhojpuri songs mixed with the cutting humour of calypso and some Reggae Riddim also talk about food and sex, while asserting their identity – of being both East Indian and Trinidadian.

Black identity, contemporary violence and sexuality are amongst the most important themes elaborated upon in Jamaican music.

Calypso mirrors these preoccupations but in an altogether different idiom. And chutney music begins to address racial tensions. Chutney rests on Bhojpuri folk, takes from Hindi film music, and lays it onto the calypso and soca. Soca refers to the dance music that emerged from Calypso music beat.

The songs of the ships have transformed, but the rhythm of the ship and the imagery of the Jahaji Bundle remain.

This was the landscape we encountered – we, a film crew, an Indian rock/pop star and the one who conceptualized this seemingly impossible journey, Tejaswini Niranjana.

Tejaswini Niranjana had completed the manuscript of her book Mobilizing India: Women, Music and Migration between India and Trinidad, a culmination of more than a decade’s worth of research in the Caribbean. She was keen on extending her academic work into another realm, she wanted to initiate “a musical adventure inspired by her research”. Listening to Remo Fernandes’ music she felt she heard strains of the Trinidadian Calypso. Intrigued, she made contact with him and many exchanges later she asked him if he might be interested in collaborations with Caribbean musicians. He responded with enthusiasm. Tejaswini saw this project as “arising directly from my work on popular music in Trinidad. I argue that much of the interaction between musics of the world is mediated by metropolitan capitals… London, Paris, New York… Here is an attempt to take south-south collaboration into the realm of musical composition and performance.”

While structuring the film I let the changes in the rhythm and the tempo largely determine the narrative – the manic potent beat of Jamaican Dancehall, the rhythm of Reggae, the same sound and the emphasis on ‘speaking out the lyrics’ spills into Rapso. Rapso is a form of Trinidadian music that grew out of the social unrest of the 1970s. It has been described as “de power of de word in the riddim of de word”. Rapso draws its biting commentary from Calypso. The dancing-to-Calypso morphs into Soca. And the Chutney has been mixed up over the years with soca giving us Chutney Soca.

Encountering traces of Hindi film music and Bhojpuri folk music seemed the least daunting aspect of filming. After all this was familiar music. The anxiety was more about dealing with musical cultures that were far removed from our experience – Dancehall, Calypso, Soca, Rapso etc.

Dancehall and Reggae are so successfully entrenched in the world music market that in fact this was the music we were most familiar with. It was the location of this music, and its significance in contemporary Jamaican culture that was far more difficult to negotiate. Whereas, Hindi film music transformed by the Soca beat was a sound that was far more difficult to understand. This was not akin to the use of a rapper’s voice in the middle of a song picturised on Akshay Kumar for instance. This was an altogether different meaning.

Riki Jai sings, ‘Bindiya Chamkegi’ and follows it up with a chorus that goes ‘Hold de Lata Mangeshkar, give me Soca’. Hindi film music was a footnote to be referenced in this Trinidadian Song.

When I screened Jahaji Music in Mumbai, a couple of Bihari women came up to me, introduced themselves as Bhojpuri singers, aspiring to break into Bollywood, and thanked me for ‘putting Bihar on the cultural map’. They sat next to me during the screening. They sang along one some of the old Bhojpuri songs were sung on screen. Later they mentioned that they were singing what they called ‘parallel songs’: Songs sung about the people who went away.

This chance encounter has led me to my next film, themes of migration and longing in Bhojpuri music. I am looking at Mumbai and other globalizing cities demanding an unending supply of informal workers from East UP and Bihar.

A temple off the Western Express highway in Mumbai is one of the places we have been going to. The shrine is at the head of a large hall. Along the walls of this large hall hang an array of known and little knows deities. Strung alongside these bedecked walls are ropes, sagging under the weight of clothes hanging all along. Under these ropes, pushed to the side, are numerous trunks. This hall transforms into a dormitory of sleeping taxi and auto drivers. On festivals, pujas, Tuesdays and Fridays, their favorite singers perform, most are fellow drivers.

Birha songs in Bhojpuri, “tumhar darad mein hum duniya dekha balma,” sings Ramanuj Pathak, a taxi driver, about a wife who laments about being left alone in the village. Pathak has just recorded a track for a Bhojpuri album, Chaar Aane ka Chumma.

An ethnographic account of these songs and the lives of those carrying these songs with them would make for a compelling film. But after working on Jahaji Music, I begin to look at displacement, migration and identity and at the thriving Bhojpuri music industry in an altogether different light. Hopefully I will be able to clarify what has changed while completing this new film.

Nice piece, Surabhi. Makes me even more regretful that I missed your Jahaji Music screening in Bombay.

Did you do a Kolkata screening – cause I missed it & was wondering how to get at least one look at this and any other film on music that you might have made or seen & would like to recommend!

Peter, shall keep you informed about other screenings.

Arpita, sorry, did not see your comment earlier. you can write to me on sh.surabhi@gmail.com

VERY informative post…..vijay is don of bhojpuri birha

bHOJPURRI SONG DOWNLOAD