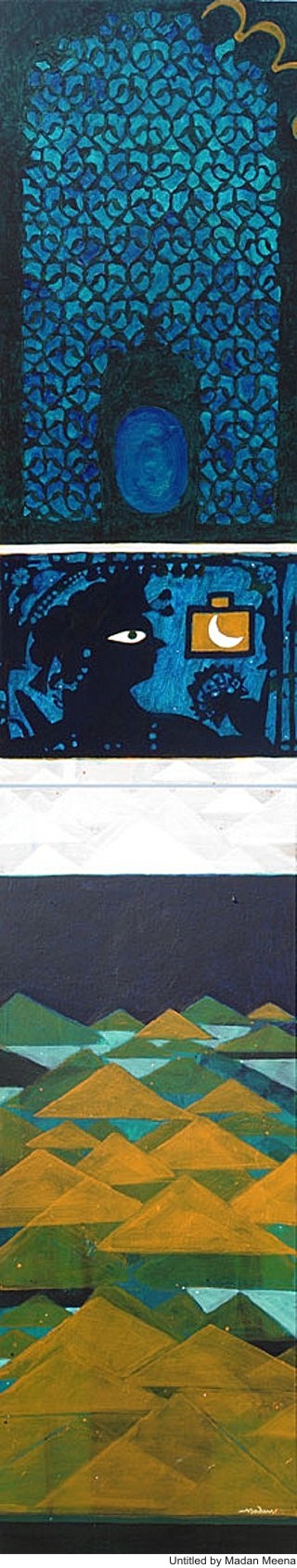

Resensualizing the Theatrical Experience: Udayan Vajpeyi

(Or, shall we call him Margi Kavalam Narayan Panikkar?)

(Or, shall we call him Margi Kavalam Narayan Panikkar?)

1.

Recently, I read somewhere that before starting his journey, wonderful for himself and more so for us, as a theatre director, Kavalam Narayan Panikkar did his law degree and, in fact, practiced law for a while.

Practicing law, what does that mean? I think it means to interpret the written law to suit the contemporary situation of the case one is handling. Someone who practices law has to relentlessly interpret the written law, interpret to contemporize it. To give it a new temporality that it may lack otherwise, which, in other words, means not to accept the law as given but to reinterpret it, reconfigure it, redesign it. Or to recreate it.

2.

Two words that, perhaps, Kavalam uses most in his conversations are Natyadharmi and Lokdharmi. With due respect and understanding of these terms and their connotations, I prefer using Margi and Deshi in their place. I will let you know the reason for that a little later. I am aware that these terms were, and are, primarily used with reference to music and dance. But then, I am also aware that Bharat Muni said that music (gaan) is the bed of theatre, gaan is the Natyashayya. Therefore, by using these terms to describe theatre, I am not too much off the mark.

Margi and Deshi are used loosely for the classical (which is, of course, a misnomer in the Indian context) and folk forms (another misnomer) but, in fact, these words have much wider and deeper connotations than these apparent meanings. Margi has come from Mrigaya i.e. hunting. Marg, Mriga and Mrigaya are all connected words. Marg is the way that one takes for Mrigaya. It is the way that one takes to search for the mriga, the animal to be hunted. One has to invent a new way every time one hunts. That’s what marg is: a new way. From this perspective margi art-forms can be seen as those where the artist incessantly tries to find a new way of creating. He or she has to be on the look out for a possible new way to create his or her art-form. Deshi art-forms are something different, but not lesser in any way. They are, ontologically speaking, repetitive in nature. Here, the artist tries to repeat the ways of creating – and rightly so, because deshi art-forms are not only a repertoire of the ways of creation and, therefore, primarily memory based, but they perform the very significant function of invoking the collective memory of the community in which they are practiced. In deshi forms, the stress is not on inventing new ways of creating but on repeating ways of creating. Margi art-forms are different, their axis lies in inventing and searching for new ways of creating. I think the margi form does not primarily evoke collective memory and, thereby, a sense of community, but stimulates the imagination of its audience to think differently, to think new and, thereby, helps them to be self-reflexive.

The mode of being of margi, as we have seen, is such that it takes much more time and effort for it to be accepted.

3.

Panikkar’s theatre, as I know it, is primarily a margi theatre. It may have and, in fact, has taken a lot of components from the deshi theater of Kerala, but he has invested them all into creating a scintillating margi theatre. In other words, this is a theatre grounded in deshi but incessantly searching for new ways of being.

Seen from this angle, his is a unique theatre: a theatre which attempts to find new openings within the deshi to create a sensuous margi theatre, thereby establishing continuity between the two or creating a scale of which margi and deshi become parts. One can appreciate the presence of such a scale not only here, but in almost every element of Panikkar’s theatre: in the aangik, the vaachik, the saatvik, or even aahary of his theatre. It is as if all the deshi components of his theatre gradually undergo a radical transformation, a kind of bhavantaran and, instead of carrying the burden of repetitiveness, they become vehicles of a search, a search for new ways of creating theatre. They, then, do not remain deshi but acquire a new life, being details of a margi theatrical experience.

4.

I will take two of Kalidas’ plays that Panikkar has presented. Kavalam’s Malavikagnimitram and Vikramorvashiyam are unique productions. Kavalam has dug out a different Kalidas from these plays; a Kalidas, of course, more suited to our times, but also a Kalidas who would have remained buried in these plays if Kavalam had not dug him out. It is as if this new Kalidas had been waiting for centuries for Kavalam to bring him out into the lights of the contemporary stage. He is the same Kalidas we have known for ages and yet, is not the same but somebody completely different.

Through his margi theatre, Kavalam is able to restate the essential feature of great writing: it is never self-same. It has many possible ways of coming into being which lie dormant in it. Whenever it is approached with an open, creative mind, it reveals its less known way of being. Kavalam has done precisely this. He approached Kalidas with his margi intentions and has brought out a new Kalidas for us.

What are those margi ways of Kavalam? They are innumerable and are there to be seen in his theatre instead of being talked about and yet, we can talk about a few. One, which is most noticeable, is his interpretation of Malavika and Agmimitra, and of Urvashi and Pururuva. In Panikkar’s theatre they are the embodiment of Prakriti and Purush. Malavika and Urvashi are the embodiment of Prakriti, and Agnimitra and Pururava are Purush embodied. But, even here, Panikkar does not accept the established Sankhya notion of Prakriti-purush. He reinterprets them and brings them close to what a poet like Bulle Shah envisaged:

Ajj ajo ki preet na jani

Laggi roz azal di aahiwe do not know what love is, in the here and now

our love has existed since the universe has existed

In the Samkhya tradition, prakriti is jad or inert whereas purush is consciousness. Prakriti functions as the medium to make purush, i.e. consciousness i.e. aatman, experience itself. Kavalam reinterprets this notion of purush-prakriti and, in fact, recasts them as lover and beloved. In other words, for Kavalam, in the light of love purush and prakriti become lover and beloved. And then he adds another dimension to prakriti: in his theatre it becomes not only the beloved but also the embodiment of nature. In this way a completely novel Malavika and Urvashi come into being. It is not something which Kavalam has added or grafted onto the plays of Kalidas, but this interpretation was waiting in those plays.

Panikkar, with his imaginative perception, allowed it to unfold and take the centre stage in his presentation of these plays. He then went one step further and, in a manner of speaking, redefined the most mysterious of all emotions: love. Love, as the mangalaacharan of Kavalam’s Vikramorvashiyam seems to suggest, is to invoke the prakriti in all its meaning within oneself. Therefore the love of Pururava for Urvashi is his attempt to find nature (prakriti) and his own nature (svabhav) within himself.

Strangely enough, as a result of the margi imagination of Kavalam, the Ashok tree comes into the centre of the Malavikagnimitram and Urvashi becomes one with the forest, where she disappears. She makes her individual appearance again only when Pururuva is able to internalize the forest and is able to see the forest as the description of Urvashi, not as aharya of Urvashi but as her aangik.

5.

The flow in Panikkar’s theatre comes not only from the flow of the narrative of the play, but more so through the use of scales. I think this is extremely significant for any theatrical practice: imaginative use of scales. There are and can be various scales in theatre. The scale of Vaachik, or speech pattern, which potentially ranges from simple straightforward speech to song. (It is interesting to note that most of the Sanskrit plays not only have more than one language, but have multiple language-gestures ranging from plain speech to slokas). The scale of aangik, or various styles of movements of actors, which ranges from a simple walk to almost-dance. The scale of syntax of the placement of actors, which ranges from the so-called realistic way, to highly imaginative ways like one finds in Kudiyattam. The scale of colours etc. Panikkar’s theatre moves in multiple axes along all these scales producing microtones (shruti) in these domains of performance. The movement along all these scales leads, in his theatre, to the unleashing of various forms of energies which prepares and makes his audience experience the cascades of rasa of the play with much greater depth and intensity. But at the same time, it also allows one to experience what Bergson called “duration”, because the movement along these scales leads to subtle disjunctions in temporalities causing various chhandas to be born. Thus allowing the audience to experience not only movements, but the material of the movements – time.

6.

The entry of Semitic religious traditions[1] caused at least one big problem in the way Sanskrit and other traditional Indian texts were read: They went through a process of desensualization. Desensualization and de-eroticization. The thing that has to be restated is that, in almost all pagan traditions, like India, the continuity of man and nature is established and practiced through erotic or shrigaar rasa[2]. It is one of ways through which homocentricity is avoided. But then the semitization of the reading of Sanskrit and other traditional texts also had its impact on the way theatre, especially Sanskrit theatre, was performed. It may seem strange, but most of the Sanskrit theatre which developed in the last century is highly de-eroticized theatre. It is not a coincidence that in most of the performances of Malavikagnimitram Agnimitra is shown as a lumpen and not a lover, without which the true erotic rasa can not emerge.

I have a feeling that Kavalam Narayan Panikkar is one of those very few theatre directors who resensualized not only Sanskrit theatre, but the modern theatre practice in India. He took his theatrical elements from all possible sources, from deshi theatre of thyyam to the much more refined margi Kudiyattam dance-drama traditions, and used them all to create theatrical experiences which are, if I may say so, truly pagan in nature. In this way, he showed not only the way theatre can be done but also gave a glimpse of the way theatre might have been done in civilizations like India.

7.

Kavalam has relentlessly tried, in his theatre, to find, what I would call, pagan ways to describe the pagan world and vision. Instead of appropriating the various manifestations of pagan consciousness into Semitic paradigms, he has tried to invent and discover unique ways of describing the traditional insights of India, those we so much need in this overtly semitized world of ours.

The lawyer in Kavalm Narayan Panikkar, whom we met in the first section of this essay, may have stopped interpreting the law, but he is working day and night with his theatre-director persona to reinterpret and recast the plays of Sanskrit playwrights like Kalidas and Bhasa, and many of his own, into remarkably innovative and sensuous yet spiritual, i.e. rasayukta, gestures of theatre to illustrate the possibility and realization of truly rooted and, therefore, truly universal artistic experiences in our times.

Notes

[1] By Semitic traditions, I mean those world views which believe that the moral or otherwise ordering of the things and human beings leads inevitably to the divine ‘grace’ as against the wisdom of the Pagans like Bulle Shah who said, ain wain chah dikhaya, ‘grace was given without any rhyme or reason’.

[2] Rati, the sthai bhaav of erotic or shringaar rasa, unlike sthai bhaav of any other rasa, is present in all the species of living beings.