Exiled from Poetry and Country: Uday Prakash

Tibet

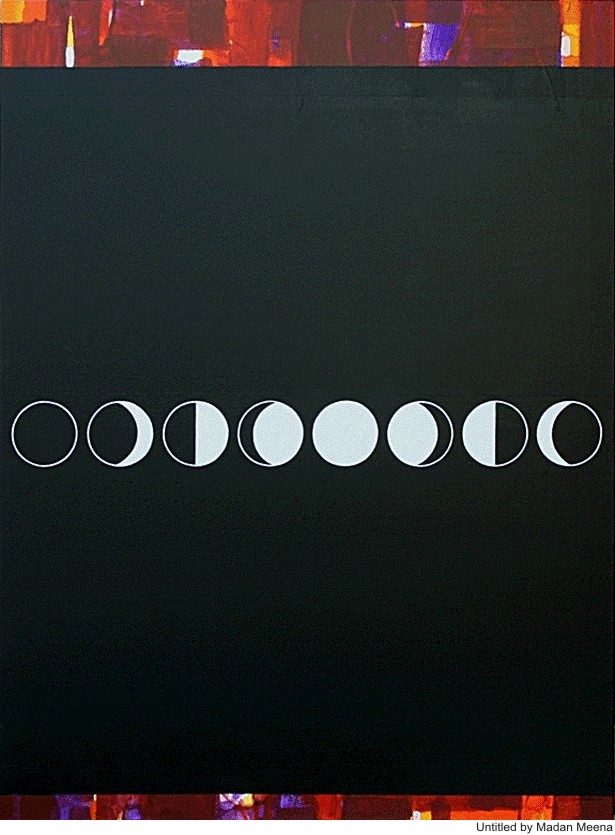

Having come from Tibet,

Lamas keep wandering around

These days, mumbling mantras

Their herds of mules

Go down into the gardens

They do not eat marigold flowers

How many flowers

On one marigold plant,

Papa?

When it’s the rainy season

in Tibet,

What season

Do we have?

When it’s three o’clock

In Tibet,

What time

Is it here?

In Tibet

Are there marigolds,

Papa?

Do lamas blow conch shells, Papa?

Papa,

Have you ever seen lamas

Wrapped in blankets

Running quickly

In the darkness?

When people die

Lamas stand

On all four sides of their graves

And bow their heads

They do not recite mantras.

They whisper – tibbut

tibbut tibbut

tibbut tibbut

tibbut tibbut

And they cry

all night long.

Do lamas

Cry just

Like us, Papa?

(Translated from Hindi by Robert A. Hueckstedt)

Exiled from Poetry and Country

1.

This happened many years ago. Most of you would not have even been born then. Nor many of today’s popular and acclaimed writers. I was born in Sitapur, a very small village in Madhya Pradesh, in the year 1952. Electricity had not yet come to our village. Our house was very old and built right on the river bank. By which I mean that when the river was in spate, the water would reach our kitchen. There was no bridge across the river. Hollowed out tree-trunks would be used as boats and punted across with bamboo poles. These boats were called dondas or dongas. When the flood was heavy and the river currents ran fast and deep, these wooden boats became useless because the bamboo poles were not long enough to reach the bottom of the river and push the boats forward.

Our village had no electricity. Lanterns, diyas and dhibris were used. I learnt to read and write, to paint etc. without bulbs, without electricity. Even today I am fond of lanterns and dhibris. Although at my age, and after having lived so long in cities, it is no longer possible for me to read or write in their light. I never liked diyas, except during diwali or other festivities and poojas. Their cotton wick, every now and then, needs to be set right which gets the fingers oily, and if you happen to be writing something on paper or reading a book then the oil stains them forever.

What I’m going to tell you about Tibet came a lot later. By that time, though electricity had still not come to our village, radios that ran on batteries had. On the batteries was a strangely elongated cat jumping out of the number nine. If I had known, then, that the company which made these batteries was the same one which, in 1984, would kill thousands of people with poison-gas in Bhopal, I would have been scared not only of the batteries but the radio as well. But I didn’t know. I loved to hear the songs and the voices of people coming from inside the radio. I had tried many times to look inside it and see exactly where those people stood, who played the instruments, who talked. Because the sounds surely came from inside the radio. Not from anywhere else. If a sitar or a bansuri played, it would seem that the sounds were born in that very place. Absolutely clear. The sudden quiver of metal wires or the susurration of breath through hollow bamboo.

If I tell you that I once saw inside the radio, late at night, in the blue-red green-yellow many-colored, dim and mysterious light of its countless tiny parts, people like puppets standing in a circle and playing all sorts of musical instruments, swaying slowly and singing – will you believe me? You will say that I must have fallen asleep beside the radio and dreamt it all up.

No adult ever believes it when one recounts such incidents from one’s childhood.

You must have read Neruda’s memoirs in which, as a child, he sees his green woolen cap, knitted by his mother, fly off from his head in a storm and turn into a green parrot that goes on and joins a whole flock of parrots. And when he tells his mother about it, she does not believe him.

If any of you have read my story Dibiya, then you might have guessed that many such incidents happened to me in my childhood. The story Areba-Pareba is also about one such incident. It is a moment of extreme solitude, helplessness and defeat when you realize that not only does such a truth have no witness, but there is no one even willing to credit it. And, more painfully, that there is no knowledge or science in the world by which you can prove it. To that I add my own private confusion – many a time I cannot even tell if what happened to me or what is happening to me, is real or a dream. What happens to the father and then the narrator in Tirichh; the part in The Girl with the Yellow Umbrella where the umbrella turns into a butterfly; or in Warren Hastings’ Bull, not just the first meeting between Chokhi and Hastings, but through the whole narrative, confusion spread from here to there, a kind of illusion. If you’ve noticed, lies and truth, imagination and fact, dream and reality, past and future are all mixed up in all my stories. To the extent that it is impossible to recognize and extricate them from each other. Even for me.

I am not able to read any story which does not have dreams or illusions. Maybe it’s because of the stories I heard in the village, epics like the Ramayan and the Mahabharat, and later the many novels and stories I read, the films I saw.

I have a similar private memory of, and relation to, Tibet. When I wrote the poem Tibet in 1977-78, it drew upon just such an incident from my childhood.

2.

I am not sure of the exact year when that incident took place. Maybe it was 1960-61. Or maybe it was a year earlier, or a year later. This much I do remember – that the frontage of our current house in the village had already been built by then. Which means that 1957-58 was past. Nehruji was our prime minister, then, and was still alive. Children used to call him Chacha Nehru. They were taught to, in the village school. The election symbol of the Congress party used to be a pair of oxen, and their party flag was just like the national tricolor except that, instead of the Ashok Chakra in the middle, there was a Charkha. It is said that Gandhiji gave Nehruji a Charkha which, after Gandhiji was murdered, Nehruji got printed on the Congress flag. In those days, during elections, pamphlets were distributed on which was written – Muhar humaari wahin lagegi, jahan bani bailon ki jodi. Who knows where the oxen have gone off to now.

The president of America, Kennedy, was still alive then, I think, and I’d keep trying to style my hair like his. When it came to hairstyles, Kennedy and Dev Anand were my ideals. I had often oiled and wet my hair, stuck a pencil in them and pressed them between my palms on both sides to achieve the Dev Anand style puff. But I always liked Kennedy’s dry hair better. The Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had, I think, gone into space and come back by then. Before that, Russia had already sent off the dog, Laika, into space. When it came to space technology, America was being left behind. My father and his friends would sit at night arguing over which one was more advanced – Russia or America – which one was more powerful and which one was our true friend. My mother was still alive, cancer hadn’t eaten away at her respiratory tract and I could not even have imagined the torture of writing the story Nailcutter. My mother and Nehruji both died in the same year – 1964. Nehruji on 27th May, my mother on 30th December. Both deaths were very painful for me. On 27th May my father said, crying, that the vessel in Nehruji’s brain had burst because of China’s treachery.

After Nehruji’s death, I made a watercolor of him on one of the walls in our home: ‘Chacha Nehru Going towards the Sunset’. Mother saw it and scolded me – Why did I not draw Nehruji’s face which was so beautiful? Why did I draw his back? Father used to say that Nehruji was so good-looking that Kennedy and Dev Anand were nothing next to him. The wife of India’s Governor General Mountbatten and some famous American actress (maybe Marilyn Monroe or Shirley McLean, or maybe someone else) were crazy about his good looks. Both wanted to marry him but he said – ‘No… No, I can not do this.’ Here, father would pause for a beat and then say – ‘Because I am already married!’ Mother used to say that Nehruji’s wife was very beautiful too, but because Nehruji went abroad and became like the English, she fell ill from living all alone in Allahabad and died.

I made many busts and statuettes of Nehruji from candles and Sunlight Soap, using a knife and blade to shape them. If any of you have read the story Nehru, Sunset and Broken Women which I wrote years ago, you’d know how deeply Nehruji was related to my childhood and my home. Here, I’d like to add that this relation had nothing to do with politics. I’ll write about all this some other time. For now, let us return to the incident which has to do with Tibet.

The day that incident took place, I had gone into the backyard to wash my hands after having eaten, in the kitchen, the rotis and aloo-parwal which my mother had cooked and which father was especially fond of. The backyard faced the river and, that day, the river was in spate. Maybe it was July, that is, the month of Aashaadh.

I was standing on a stone near the kitchen’s back door, washing my hands when I saw what would become the reason for writing Tibet years later.

My age at that time, as you might have estimated, was about 8 or 9. I used to draw a lot, write poems, and was caught up with trying to make prints of some 120 black-and-white photos that I had snapped with an old Rolicord camera. My brother was my guru in matters of technology. Those of you who have read the stories Crime and Brother’s Satyagraha will know that polio at the age of five had left one of his legs lifeless. Even so, no one could beat him at cycling or swimming.

At our home, we used to get a newspaper called the Bharat which was printed in Allahabad, and sometimes the Nav-Bharat as well. Besides which, we also got a lot of magazines which father would read sitting in his cane chair in the verandah, or sometimes, under the jackfruit tree just outside our house. Father loved books and cane chairs, and he would order them from Allahabad. We also had a gramophone which didn’t work. You could key it up and the record would start to spin, but its spring was broken and the sound-box had rusted and become useless, so it was kept up in the loft. We already had the radio by then and so the gramophone was forgotten.

Which is what always happens with technology. The craze of a time turns into the trash of another. Puffed up with its proud past, rusting. But then, the same is true of people as well.

Both my brother and I would spend days and nights trying to figure out how to breathe life into these old, dumped things. The disc that played on the gramophone – called ‘record’ by city-dwellers – was called ‘tavaa’ by the villagers. It was made of leather or lac and looked exactly like the iron griddle on which mother used to make rotis in the kitchen. Our loft had countless such tavaas. Anmol Ghadi, Aah, Aag, Jaal, songs from who-knows-how-many films were trapped in the lines on those tavaas which came to life under the gramophone’s needle.

How strange it seems, now, to think of the lac-insects sucking pulp from the leaves and trunks of the palash and chhiula trees and secreting lac from which those records were made in whose grooves, when the needle ran, songs began to play – Mera sundar sapna beet gaya or Awaaz de kahaan hai, duniya meri jawaan hai. Was not this wonder the result of the magical coming-together of biology, i.e. the lac-insects, and record companies from Germany to Calcutta?

Which is why I cannot ever think of any technology, however new, as inhuman or unnatural, the way people often do. It is, rather, the use of technology that determines this.

3.

In that village – where electricity hadn’t arrived, where there were no roads or bridges, where school was run on sack-cloths in Mahesh Singh’s cow-pen from which the cows and buffaloes had gone and where we learnt to write the alphabet on wooden boards with reed quills and ink from clay inkwells, but still, one where the radio had arrived and where one could get newspapers and all sorts of magazines – my brother and I developed many ‘technologies’. Our village was not different from Marquez’s Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude. These accomplishments of our childhood were no less exciting than the scientific/technological discoveries being made in Macondo.

A flashing bulb made from batteries, magnets and a strip of tin. Copper wire insulated with candle-wax and armature bound, to make a little fan that astonished mother and maybe scared her a little. A telephone line connecting our house to Tirra-Kirpaal’s house, made from a kite-line and two empty boxes. Projecting the outside world upside down, in motion and color onto the wall of a darkened room by making a pinhole in black cardboard. A kaleidoscope made by turning the glass strips of a Petromax (what was called gas-batti, or gaslight) into a pyramid and wrapping it with black paper and filling it with colored bits. Sparks made from rubbing flint and iron. ‘Permanent matchsticks’ made from moonj rope… And prisms! And yes, like Colonel Buendia from Marquez’s Macondo, innumerable games of lenses and sun and focus and fire.

But some of our technology was cruel and merciless too. For example, catching large butterflies or moths and tying empty matchboxes or other stuff to their tails with bits of string. Tying little cardboard boxes to black beetles and then filling them up with pebbles to test the strength of our living trucks. Now I look back and think – how those beetles must have suffered! And the bloodsucking leeches that clung to our legs when we crossed the puddle by the lake, on the way to school – putting a pinch of salt on them and then stretching them out and pinning them onto a wooden board and playing them like an ektara. Or catching hold of their necks and rubbing them against stones, the way we’d learnt from monkeys, or thrashing them again and again against a tree trunk. (I’ll write about all this, at length, some other time, and about those wild younglings that we tried to domesticate.) Often I think that there are so many cruelties in tribal societies… cruelties towards other living beings… but when you compare it to the massacres and wars and the destruction of the environment and people perpetrated by these so called advanced and modern civilizations, doesn’t their violence seem like child’s play?

So that was the sort of time it was when we saw in our village, for the first time, Lamas who had come from Tibet. Saw their families. Father told us that China had attacked the Lamas’ village, Tibet, and they had fled and come to our country. They would live on the mountains of Sarguja where the Pahari people and Lamas lived. We used to call everyone from Tibet ‘Lama’, then. The place they intended to settle in was called Mainpat.

Three kilometers from our village was the Anuppur railway junction. Some of you might have read the poem Anuppur Junction from my first collection of poems Suno Kaarigar which Baba Karant liked very much. This was a small junction where, even today, one has to change trains if one wants to go to Sarguja, that is, Ambikapur. If you want to go to Amarkantak, which is the source of both the river Narmada and the river Son, you have to get off at Anuppur. So now you know that my village is near the source of these two big rivers. In Hindi, the Son is called ‘nad’ instead of ‘nadi’ – that is, a ‘male river’. It is called ‘bhadra’ in the Puranas. One of the five male rivers in the country, apart from the Vyas, the Brahmaputra, and the Indus. It’s said that Son was going to marry Narmada. The mandap was ready, the pheras were about to be taken. But then, suddenly, Narmada got angry, broke the wedding knot and started running in the opposite direction. Because Narmada was a ‘kul-sheela’ – one belonging to an upper caste – and Son had become ‘kul-bhrastha’ – or defiled – because of his affair with a lower caste girl called ‘Juhila’. If you look at the map of the Vindhyas you’ll find that the Juhila is also a river, albeit a small and rather slender one. And that, after a tortuous and difficult route of a hundred and fifty kilometers, it goes and meets with its outcaste lover Son near Katni. Then, in Bihar, both dissolve into the purifying, moksha-giving Ganga. Whereas the haughty Narmada can never meet the Ganga. It is the only river in India that runs from north to south-west, that is, in the opposite direction. People in our village say – ‘Look at how fortunes turn, look at god’s ways. The outcaste Son, with Juhila, drains into the Ganga and attains salvation, while proud Narmada falls into the lap of a lecher.’ Varun, the god of the sea, was held to be a lecher, like Indra and Kuber. One who flirted with all the yakshinis. Now when I see the Narmada and the whole Sardar Sarovar to-do, I think that the Narmada was truly unfortunate. Even today Kuber (money) and greed have it chained. Was she punished for her pride? I have started rambling again…

We were talking about refugees from Tibet, all of whom we called Lamas. So… The Lamas would get down with their families at the Anuppur railway platform. They had to wait for hours for the next train. Sometimes, especially during the rains, that lone train to Sarguja would get delayed and cancelled for days due to floods and water on the tracks. Then, the Lamas would come out onto the sands of the river bank. There, they’d eat, bathe etc. Seeing them there was something utterly new for us children. Remember, there was no television then, and the cinema hadn’t reached our village. Most of the people from our village and the neighboring villages were dark skinned. My cousin brothers and sisters were dark too. But the Lamas were fair and very beautiful. Their women and children too were beautiful – so beautiful, in fact, that seeing them our eyes would forget to blink.

The Lamas used to love children. They’d bring out ‘lemonchoos’ and sweet candies from their ruddle-dyed bags and give them to us. They always seemed to be smiling. Their eyes, their faces, whenever you saw them, seemed to be smiling or softly laughing. And full of a strange sort of peace… And the red-robed, tonsured old Lamas – it seemed as if their whole bodies were steeped in a soft smile.

The villagers used to say that these were people who worshipped the God Buddha. So was it the Buddha’s smile that you could see in their bodies, in their whole presence? The same Buddha smile for which, 37 years later in 1998, India’s self-proclaimedly religious government named a nuclear bomb that it exploded at Pokharan?

Father once told me that Rahul Sankrityayan had devised the grammar that the Lamas used. The same way the Tamil grammar was devised by the saint Agatsya. Which is why they thought of Rahul Sankrityayan as their guru in language, and Buddha as their guru in religion. I don’t know how much truth is there in these statements, but I do remember that this is what father told me. I’d often feel like running off with the Lamas forever to the mountains of Sarguja. And while this was because of the lemonchoos and candies they gave us and their mysterious persona and the magnetic Buddha smile – it was also because of the great fear that clouded my childhood.

That was the fear of Mahesh Singh’s cow-pen school and the Shiv-Bhakt teacher Rajmani Singh – he of the moustache, the muscles and the ash-smeared forehead – whom I had named, in anger, fear, and with a measure of gratification, ‘Raj-Mataa Singh’ (‘Mataa’ being the large black ants, with very painful bites, found in Mango and Jamun trees)

Raj-Mataa used to beat up students who didn’t learn their tables, with a switch made from Sirkin reed or hemp. He’d pull at the hair on our temples. Or make us hang for hours, legs crossed, from a wooden crossbar while he went off to play cards at some junkie’s. There was probably no law, then, against cruelty to children or, if not anyone else, I would have lodged a case against him. In comparison to the demoniac Raj-Mataa Singh, the Lamas from Tibet seemed to us prophets of pity, compassion and love. Many a time I planned to run away from my home and village with them. I don’t know why I never actually did.

Many years later, I read a story by Borges, or maybe it was some other Latin-American author, in which a man from some city in America keeps dreaming for years of snow-capped mountains with dwellings at their feet and a caravan of people walking upon a track. He starts feeling like a stranger or and émigré in the city that he has lived in all his life. And then he starts feeling that his wife, his children, all his family are strangers…

Then, becoming restless, he sets out in his old age to find that place which he’d been dreaming of since childhood. And in the end, after wandering the whole world, he reaches Tibet and is stunned. The same snow-capped mountains, the same dwellings, and a group of people in a caravan exactly like he saw in his dreams. Just then, a woman in the caravan recognizes him and runs to him with two little children, calling out his name in Tibetan, almost out of her mind and wraps herself around him and starts crying. The two children wrap themselves around him as well. And so the man who had lived in a strange city, in a strange country, among strangers, is recognized at last. He comes to know his real name and lives there with his family ever after.

4.

It must have been the month of Aashaadh.

The rain that had been falling continuously for the past few days had stopped but it left behind a heaviness, a dampness in the air and dust. Maybe it was the first rain of Aashaadh. The first drops of rain fall on the earth burnt by the summer months of Vaishaakh and Jaith and cool it down. Like drops of water sprinkled on a hot griddle. And then that scent of wet dust turns into steam and scatters all around. We breathe deeply and know that the rains have come. It’s said that the great painter Picasso, in the first rains of the season, seeing the gathering clouds, would go onto the rooftop and start dancing. The coming of rain is always a great and magical moment, for the world, for our lives. I have searched for it everywhere but no perfumer makes a scent that can bring to mind the scent of wet dust that springs from the earth during the first rains of Aashaadh.

After these rains, ants suddenly come out from their colonies under the earth, where they’d been hiding all summer, and start flying about in the evening sky. These are ants that have grown wings. Swarming out towards the sky, they hover over the courtyards. But their wings are so fragile that the slightest gust of air, or an over-excited gesture, can break them. Then they fall to the earth, helpless and, back in their original form, start crawling about in search of shelter. In these few moments of their life we know these ants as patangas. Wherever they see light, from electric bulbs or lanterns or kandeels, these groups of patangas gather. The cool of the first rains of Aashaadh, or the lights from bulbs or lanterns or kandeels which had brought new hopes for the future into their lives, are soon revealed for what they really are. Each morning we sweep out the countless dead bodies of these ants that, with weak wings sprouted, had rushed towards the sky, towards light, in a collective optimism. Their momentary curiosity and hope filled life has, by morning, turned into a pile of trash. This little chapter in the lives of winged ants is probably a story, in the history of their civilization, of the making of a Utopia and its subsequent loss. Just like a chapter in the history of human civilizations.

So, it was some night like this. A night after the first rains of Aashaadh. That night the river was in spate. If it rained again in a day or two, it would be flooded and the river would start flowing outside our kitchen. In the night, everywhere, there would be snakes, tortoises and centipedes washed up by the river. It was also the time for frogs. Meditating or hibernating in some crack in the earth for months, these frogs, of various types, would also come out with the first rains and we would hear them croak all night. Frog-tunes. A strange sort of music. Cicadas on guitar, the peal of a sentinel bird, and the mandolin or bansuri of some night-bird in the distance, for accompaniment. That night, mother had cooked aloo-parwal. Father’s choice. Like always, I was making something, or reading something. Irritated by, and muttering about, the winged ants that would keep falling on the pages of the book or on me or on my lantern. One had to be very careful while eating at night. Once, someone had come over for dinner and was eating in the dim light of the lantern, and when he tried to pick up the achaar from his thali, the achaar let out a strange sound and flew off. We’d be wary of putting our feet into shoes at night. Who knows, a frog or snake or some other creature might be sitting, hidden there. One night when my uncle reached for the torch by his head, it ran off with a squeal. Maybe a mongoose or an otter had taken shelter from the rain under his pillow.

I’d always eat with mother. When everyone else had eaten, mother would sit down with whatever was left for her. Of course, she would always have kept something aside for me. After eating, when I got up and opened the backdoor of the kitchen to wash my hands and gargle, the roar of the river, the sparkling darkness and the countless sounds of night surrounded me. If you live by a river, you’ll know how wonderful and mesmerizing this can be. Something that can surround you and drag you within itself and overwhelm you. But always with a hint of fear and nightmarishness. A rare experience: standing alone at night by a river frothing in flood. As if bewitched. Yet with fear simmering inside. Still, unwilling to step away. And at that moment, my eyes focused in the dark on the other side of the flooded river. Once, years ago, there used to be a temple there with a statue of Buddha. Tathaagat. But he’d been kept with gods and goddesses, anointed with a tika of sandalwood paste. They called him Siddh-Bhagwan. In this whole region, even today, one keeps finding many old, broken statues of Buddha. It’s usual to find such statues when one digs for a well or to lay the foundation for a building. The region of Kaling – where the attacking armies of King Ashok massacred the unarmed poor and peaceful people who nonviolently opposed him, and then, by the time he reached Rajgir-Udaygir in the south-east, already repenting of his violence, he turned Buddhist – the borders of that same Kaling are near these Vindhyas. I often wonder who those people were who broke these statues of Buddha and made temples in their place. Brahmins? Some Hindu Taliban from ancient history? Or someone else? That night, on the other side of the flooded river, yellow red blue flames of fire seemed to be walking about in some sort of order. As if people with small torches in their hand were moving in a circle. In our village it is believed that, in the night, the wood of the Chitavar burns in this manner. And if it is dipped into the river, it turns into a snake. But it is not easy to get hold of a Chitavar. If one does, it works like a philosopher’s stone. Meaning, any metal touched by the Chitavar will turn into gold.

In our childhood the Chitavar was present in our fantasies the way, ages ago in Arabia, Egypt and Mesopotamia, the alchemists fantasized about discovering some chemical formula that could turn base metals to gold. Because every sort of matter is, in reality, one. Only its internal structure makes it different from others. The same search for a formula to change the internal structure of matter continued for centuries and gave birth to the science we today know as ‘Chemistry’. Was there some science, which has not yet been discovered, behind the story of the Chitavar that was prevalent in our Macondo-like village? Or was it just a communal belief? A pre-modern misconception? A superstition? Later, when I was studying in the eighth grade, our chemistry teacher Vermaji – who was dark complexioned, had a pockmarked face and whose eyes were always red – told us that, in the night, phosphorus from the bones of dead animals and humans oxidized in this manner and people got frightened.

5.

That night, in the month of Aashaadh, across the river, on the opposite bank, mysterious little flames of fire were strolling and sparkling hazily. Between the distance that separated us – the flooded river, its fast current and its angry roar. I called mother and said, ‘Mumma, look! Across the river Chitavars are burning.’ Mother got up and came. She peered intently and said, ‘Listen, can you not hear voices… of men?’

I listened carefully. Slowly, voices of men drowned in the roar of the river and other night-sounds started coming through. A few moments later it seemed as if there was something musical about it. The repetition of a few sounds.

Mother had gone back inside the kitchen and I was standing there quietly. Wanting to look at those hazy colored lights that strolled about and the voices that arose from there. A little while later, human shapes became discernible in that far-off circle of lights. Unclear, unsteady, but living human shapes, certainly. Something similar to what I had once seen, as a child, inside the radio but which, later, had been rejected as a dream by adults. I had decided, then, never to tell anyone else about any such incident that happened to me which they would not believe. If you read my very early story, Dibiya, you will learn more about this decision.

That night too, I was thinking the same. It had become clear to my eyes that, across the river, the shapes that carried the little lamps and continuously repeated words in some sort of flow were none other than the Lamas. Father said that China had invaded their village Tibet and they had left behind their houses, left behind everything and escaped to our country. Now they would go and live on the mountains of Sarguja, at Mainpat, where the ‘Pahari Korba’ and ‘Oraanv’ lived. So this meant that the play of fire across the river was not the Chitavar, not the phosphorus from the bones of dead men and animals burning in oxygen, not some illusion or dream, but something real happening there. I do not know how long I stood in the kitchen’s backyard, at the edge of the flooded Son, seeing those lights in the darkness across and trying to hear the words rising from there in silent concentration.

Mother had eaten. The leftovers were kept in the almirah. The dishes were gathered. After that she came out and asked me, ‘Did you find out anything? What people are they?’ And in answer I only said, ‘They seem like Lamas to me,’ and was quiet. But, truthfully, that night I felt certain that the music coming from there was not some song, but a chant in which some painful lament was mingled. As if someone, crying with all his heart, body and soul, with his whole being, was praying in some sort of dirge or elegy. The next morning, the river was flooded even more. In such a flood, our hollowed-trunk boats could no longer run. The bamboo poles were not long enough.

In the morning, I went again to the backyard and looked at the place where that incident had taken place last night. But no one was there. The place was deserted, and because of the flood I couldn’t reach it.

Many days later, I found out from people of the village that the train from Anuppur to Sarguja had been cancelled for five-six days and, on the station’s platform, a sick Tibetan refugee had died. Which meant that, that night, the Lamas had come to the riverbank to perform the last rites for their companion.

I do not know, even now, how Lamas perform the last rites for their dead. Do they bury them? Do they burn them? Or do they, like the Parsis, leave them somewhere or float them in a river? But this much I do know – that when a Tibetan dies in some foreign country, hundreds of miles from home and country, then the Lamas’ prayers or chants sound, more than anything else, like a lament. Unsettling. Piercing the heart.

And if someone is not merely a politician, if something human still remains inside, then this lament never leaves the memory. For me, it has become even more unforgettable because, after mother’s death, I left the village and then, after father’s death, there was nothing there to return to.

Years after this incident, in 1975-76, when I was research student at JNU, where I would also teach for a while, I read, in its library, a story by the world-famous writer Asimov. (Translator’s note: The story is actually “The Nine Billion Names of God” by Arthur C. Clarke. You can read it here.)I can never forget that story. I’ll summarize it for you, from memory:

Two language-experts from America find out from somewhere that there exists in a Buddhist monastery in Lhasa a manuscript, written in an ancient script, which contains the secrets of the universe’s creation and destruction. But the problem is that, like the script found in Mohenjo-Daro, experts from the world over have not been able to decipher this unknown script. Experts, not only from the west or from America but from many other countries, have stealthily copied out some pages from the hundreds of pages of the manuscript and taken them back and slaved over them but without success. According to Lamas of the monastery, it is forbidden to translate or interpret this unknown script in some other language. According to their belief, the day someone decodes the manuscript in its entirety, the entire universe will be destroyed.

Those two Americans spend day and night studying the unknown script. Many years later, they succeed in decoding it. They take a small two-seater plane to Tibet and meet the Lama there, expressing their desire to see and read the mysterious manuscript.

Though the Lama gives them permission to see it, he sternly warns them not to decode it or try to translate or elucidate it in some other living language, otherwise the universe would end. Both the experts go to the monastery everyday and start decoding the manuscript. Because they know that the Lamas’ belief is nothing more than some superstition born in pre-modern, pre-scientific times. In about two months, after days and nights of hard work, they reach the last page of the manuscript. Then, the last paragraph. And then, only the last sentence remains. Now, they both face a dilemma. A dilemma which also has an element of fear. What if the Lamas’ ancient belief is true? In the end, they decide to decode the last sentence anyway and, in a few moments, they complete it.

They come out of the ancient monastery in Lhasa. Outside, the snow is still the same, it is as peaceful as before, and the movements in the dwellings are also the same as before. Nothing has changed. Both of them laugh. That night, they take leave from the Lama and set off for America. On one hand, there is the pride at having decoded, and translated into a modern language, a script which had remained unknown and undecipherable for so many years. On the other hand, there is the happiness at the old Tibetan superstition being proved wrong. Both are intoxicated and drinking ‘chhung’, a Tibetan wine.

But at that moment, the pilot of their aircraft says in a frightened voice, ‘Sir, Look ahead. What is happening?’ Both the experts are stunned. They see – all the stars shining in the universe are going out one by one.

If you read my story Warren Hastings’ Bull, then you’d know well its protagonist-bull, who was given to Samuel Turner by an old Tibetan Lama, and who was, in fact, a yak. Read the story’s last lines once more:

By the way, that old Lama still lives as a refugee in that part of Delhi known as ‘Majnoon ka Teela’. He remembers Samuel Turner whom he met about two hundred and twenty five years ago.

Smiling through his mysterious wrinkles, the Lama says, ‘That bull is not dead.’

(Translated from Hindi by Rahul Soni)

(To read the original Hindi versions – of the verse and the prose – click here.)

What a meandering river like tale Uday Prakash writes in his ‘Exiled from Poetry and Country’

With great gems of insite about his story telling style…

‘If you’ve noticed, lies and truth, imagination and fact, dream and reality, past and future are all mixed up in all my stories. To the extent that it is impossible to recognize and extricate them from each other. Even for me.’

It was a delight to read – thanks